openSUSE Tumbleweed – Review of the week 2022/36

Dear Tumbleweed users and hackers,

As we are used to by now, Tumbleweed is kicking and rolling. 7 snapshots in a week would be nothing surprising. Unfortunately, this week we ‘only’ reached 6 snapshots. Number 7 was discarded – not for having issues, but the next snapshot passed so quickly through OBS that it was ‘ready for testing; before openQA could even finish the previous run. Not something we see very often. In any case, no harm done: you just needed an extra day of patience to get some of the updates.

The 6 snapshots published were called 0901, 0903, 0904, 0905, 0906, and 0907 and delivered these changes:

- Linux kernel 5.19.7

- libssh 0.10.3

- SQLite 3.39.3

- NMap 7.93

- Mozilla Thunderbird 102.2.1

- librsvg 2.55.1

- SETools: no longer recommend python3-networkx, which pulled in way too much, incl. pandoc

- NetworkManager 1.40.0

- Flatpak 1.14.0

- GCC 12.2.1

- Libvirt 8.7.0

In the future, near or far, I predict these changes to reach Tumbleweed:

- Mozilla Firefox 104.0.2

- KDE Plasma 5.25.5

- GTK 4.8.0

- Mozilla Thunderbird 102.2.2

- LibreOffice 7.4.1

- libxml 2.10.2

- Linux kernel 5.19.8

- KDE Gear 22.08.1

- grep 3.8: declares egrep and fgrep as deprecated. Switch to grep -E resp grep -F

- util-linux 2.38.1: this also brings a massive package layout change, which will probably take some time to settle. It’s part of the distro bootstrap and we have to be careful to not blow it out of proportion

- fmt 9.0: Breaks ceph and zxing-cpp

- gpgme 1.18: breaks libreoffice

- libxslt 1.1.36: breaks daps

Leap Micro 5.3 Beta Available for Testing

Leap Micro 5.3, which is a modern lightweight host operating system, is now available for beta testing on get.opensuse.org.

The beta version is only expected to be available on openSUSE’s website for a couple weeks before it quickly transitions to a release candidate.

Leap Micro is an ultra-reliable, lightweight and immutable operating system that experts can use for deployments; it is well suited for decentralized computing environments as well as edge, embedded, and IoT deployments. Developers and professionals can build and scale systems for uses in aerospace, telecommunications, automotive, defense, healthcare, hospitality, manufacturing, database, web server, robotics, blockchain and more.

The host-OS has automated administration and patching, so auto-updating gives users a persistent bootable system for their container and virtualized workloads.

Leap Micro has similarities of MicroOS, but Leap Micro does not offer a graphical user interface or desktop version. The OS is based on SUSE Linux Enterprise and Leap rather than a variant of Tumbleweed, which MicroOS bases its release on. The biggest changes to the newer version are NetworkManager as a new default and related tooling like Cockpit plugin, ModemManager, wpa_suplicant and addition use for Amazon ECS. There is a shorter cold boot time (shorter timeout) and the use of jeos-firstboot for post deployment configuration (root password, etc.) for those who don’t use ignition or combustion.

One of the packages related to Leap Micro for developers is Podman. Podman gives developers options to run their applications with Podman in production and the upgraded 3.4.2 version brings new pods support for init containers, which are containers that run before the rest of the pod starts.

Large development teams can add value to their operations by trying Leap Micro and transitioning to SUSE’s SLE Micro for extended maintenance and certification.

Testers can file a bug against Leap Micro 5.3 on bugzilla.opensuse.org.

Users should know that zypper is not used with Leap Micro, but transactional-update is used instead. Documentation from Leap Micro 5.2 can help users who have questions about running this modern OS, which targets edge computing.

openSUSE Leap Micro has a six-month lifecycle.

To download the ISO image, visit get.opensuse.org.

Tumbleweed Ends Continuous Streak, Keeps Rolling

The Tumbleweed continuous daily-release streak ended last week with a new record of 26 snapshots, but openSUSE’s rolling release doesn’t appear to have slowed down in any way with the frequency of snapshots that continue to roll.

Snapshot 20220829 broke the streak, but this week continued to fast forward with several snapshots and package updates.

Before highlighting those snapshots,GNOME 43 might need some love before making it into a Tumbleweed snapshot. Please read the tweet below and chat with the team on https://matrix.to/#/#gnome:opensuse.org if you are interested.

The @gnome 43 release candidate is packaged up in @openSUSE's GNOME:Next, which is our unstable branch. The extensions haven't been tested. Looking for people to test. Chat at https://t.co/iEBQH4ZRt9 for more info. pic.twitter.com/nTJuOkZ6ae

— openSUSE Linux (@openSUSE) September 7, 2022

The latest snapshot to be released was 20220907. The update of gnome-bluetooth 42.4 has its Application Programming Interface now export the battery information for all Bluetooth devices listed in UPower. Files and scripts for MicroOS were updated with microos-tools 2.16. An update of libsoup 3.0.8 had mumerous improvements to HTTP/2 reliability and fixed an http proxy authentication with a default proxy resolver. SVG rendering library librsvg updated to version 2.55.1 and is experimenting with giving librsvg an even-odd versioning; odd minor versions will be considered unstable and even minor versions will be considered stable. This should be fun! A few other packages updated in the snapshot, which including kernel-firmwarel 20220902 and yast2-vpn 4.5.1 and more.

The Linux Kernel updated from version 5.19.2 to 5.19.7 in snapshot 20220906. There were a few btrfs fixes and changes along with amdgpu driver updates in Kernel. An update of userspace-toolset package lvm2 2.03.16 had some segfault fixes, added several patches and fixed the loss of deleted message on thin-pool extension. A change for virtual reality was made with a Plymouth 22.02.122 update because displaying a boot screen on VR headsets isn’t necessary. Or is it? Text editor vim 9.0.0381 fixed some crashing, flickering and a Clang static analyzer that gives warnings. Updates were also made to sqlite 3.39.3 and other packages in the snapshot.

Just two packages updated in snapshot 20220905. Network Mapping tool nmap 7.93 was released to commemorate Nmap’s 25th anniversary. Congrats! The tool upgraded several libraries and ensures Nmap builds with OpenSSL 3.0 while using no deprecated API functions. The package also fixed a bug that prevented it from discovering interfaces on Linux when no IPv4 addresses were configured. The other package to update was Thunderbolt 3 device manager bolt 0.9.3. The update created a work around glib.

A bit more than a handful of packages were update in snapshot 20220904. The packages update in the snapshot were AppStream 0.15.5, git 2.37.3, libstorage-ng 4.5.43, libzypp 17.31.1, zypper 1.14.56) and gc 8.2.2. The update of git corrected some regression and made some git fsck improvements. openSUSE’s zypper made sure up respects solver related command-line interface options.

The update of btrfs arrived in snapshot 20220903. The filesystem update provides some optional support for LZO and ZSTD compression. The update also brought some compatibility with glibc 2.36. An update of GNU Compiler Collection 12.2.1+git416 had some recently backported fixes from trunk and had some changes for armv7l architecture. Pixel encoder and color-space converter package babl 0.1.96 dropped some patches and fixed a crash on non-aligned data for Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD). Other packages to update were libvirt 8.7.0, lsscsi 0.32, upower 1.90.0 and several RubyGems.

The first snapshot since the streak was broken was snapshot 20220901. This snapshot updated curl 7.85.0. Contributions from 79 people were made in the new versions. A Common Vulnerability and Exposure was fixed in the release. CVE-2022-35252 was introduced in curl 4.9 and allowed a “sister site” to deny service to siblings. The release also added Transport Layer Security 1.3 support. An update of NetworkManager 1.40.0 can now restart DHCP if the MAC changes on a device. Some internationalization and localization changes were also made with the network package. An update of Flatpak 1.14.0 improved support for transferring files between two local devices known as sideloading. That software deployment and package management utility also added a package configuration for libcurl to enable the new HTTP backend. Other packages to update in the snapshot were ncurses 6.3.20220820, grilo 0.3.15, mariadb 10.8.3, a kdump git update and more.

The syslog-ng Insider 2022-09: 3.38; SQL; disk-buffer; nightly;

The September syslog-ng newsletter is now on-line:

- 3.38.1 released, 4.0 almost feature complete

- syslog-ng Store Box SQL source

- Why is my syslog-ng disk-buffer file so huge even when it is empty?

- Nightly syslog-ng builds for Debian and Ubuntu

It is available at https://www.syslog-ng.com/community/b/blog/posts/the-syslog-ng-insider-2022-09-3-38-sql-disk-buffer-nightly

syslog-ng logo

Calling an Expert | Three Commodore 64s Back from the Dead

Working From Home

The first week of the COVID lockdown, back in March 2020, a journalist friend of mine started a Hungarian Facebook group to share work from home experiences. As I have worked from home all my life (except for two weeks), I wrote a long post about my experiences and thoughts. 2.5 years later, my post still receives some occasional likes, and someone even quoted from it – without naming the source :/ You can read the English version of my original Facebook post below.

I would not call myself an expert on remote work, but as I have been working from home for the past 20 years, I will share some of my experiences.

To be more precise, it started 25 years ago. As a student job, I helped running one of the first web servers of Hungary from home, late in the evenings, in my free time.

Later, as a PhD student, I only traveled to the university campus (in a small town, close to Budapest) when I really had to. Essentially, I was there only when I had to attend or give a lecture. I did my research experiments when I had to be in Gödöllő anyway.

After graduating from university, I worked from home for a small US-based company. I never met my boss while working there and met only one of my colleagues at a conference in Brussels. I only met my boss seven years later, when I gave a talk at a conference in Washington, D.C.

These days, I am still predominantly working from home. I go to the office once a week. That’s when I have my English lesson, team meetings, and so on. (Editor’s note: this is called a hybrid work method nowadays)

And now, here is my list of WFH experiences, which of course might differ from your experiences:

-

Working from home is difficult without motivation in your job, and it is difficult to stop when you are motivated :-) I belong to the latter group: most of my work I would do as a hobby as well. This means that most of the time, it is difficult to stop working and switch to other tasks. If you have minimal motivation, or nothing at all (other than your salary), you most likely need to be in the office and experience peer pressure to be be able to work.

-

Self-determination. It does not mean that you do not discuss your task list with your line manager, of course. However, if based on these discussions, you cannot work on your own, prioritize your tasks, and manage your time, working from home will be difficult for you. On the other hand, if you can present what you would like to work on (and why is it important for the company), it also helps you work on interesting challenges.

-

You are part of the team, even at home. If you do not feel like you are, home office is not for you (or it will be a lot more difficult, at least). I guess it also has to do with being extroverted or introverted. For introverts, working from home is easier, as they even require regular alone time. I belong to this category as well.

-

Communication. No matter where you are working from (a park, the top of a mountain, or the sea shore), your team relies on you, and you can rely on your team. During work hours, you must be accessible, just as if you were in the next room. Unless it is a really critical situation, communication should be asynchronous. What does that mean? Phone or WebEx should be a last resort. Asynchronous communication means that you react quickly, but not necessarily immediately, to incoming questions or requests, without interrupting your current task. During my university years, we used e-mail communication. At the US-based company, we used IRC. At my current workplace, we currently use Teams, but previously we also used Hangouts and Slack as well. Distance must not be a communication barrier. (Editor’s note: asynchronous communication is practically any kind of chat)

-

Humor, stress reduction. These belong with communication, but it is worth giving them an extra emphasis. When you are in the office, you can have great discussions over coffee / tea / cigarette (well, this last one is not for me), laugh at jokes, or reduce stress through talking. This must also work online. We have some dedicated Teams channels for these kind of discussions. However, we do not mind if our meetings have a few funny moments as well.

I guess there are many other WFH topics, but these came off the top of my head.

In the past 2.5 years, most people were forced to work from home for shorter or longer periods of time. Many kept on working from home even after return to office (a.k.a. RTO) became possible. I have talked to quite a few people about WFH recently, and I think most of my points are still just as valid today. What do you think? You can reach me on Twitter and LinkedIn.

YaST Development Report - Chapter 8 of 2022

Time for another development report from the YaST Team including, as usual, much more than only YaST. This time we will cover:

- The fix of an elusive YaST bug regarding the graphical interface

- Initial handling of transactional systems in YaST

- A general reflection about 1:1 management of transactional systems

- Some improvements in the metrics functionality of Cockpit

Let’s take it bit by bit.

Hunting YaST Rendering Issues Down

Over the last year or so, we got some reports about the graphical interface of YaST presenting rendering issues, specially on HiDPI displays and on openQA. The reporters provided screenshots that showed how some widgets were apparently drawn on top of the previous ones without an intermediate cleanup, so the screen ended up displaying a mixture of old and new widgets that were very hard to read.

We were unable to reproduce the problem and we tried to involve people from different areas (like graphic drivers maintainers, virtualization experts or X11 developers) to track the problem down with no luck… until now! We finally found where the bug was hiding and hunted it down.

See the pull request that fixes the issue if you are interested in a technical description including faulty HiDPI detection, unexpected Qt behavior and QSS style sheets oddities. It also includes a screenshot of the described (and now fixed) problem.

YaST on Transactional Systems

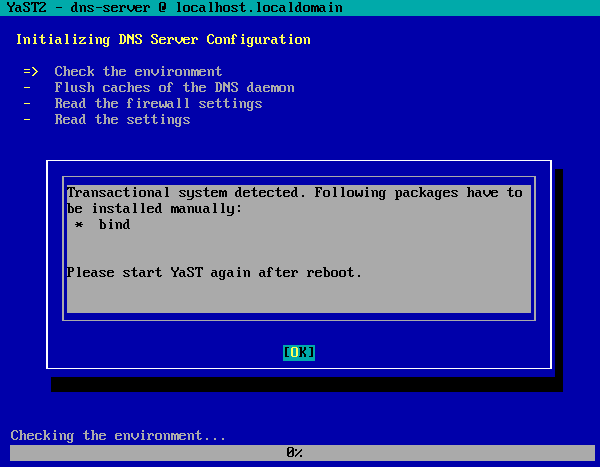

And talking about YaST and known problems, you may remember from our previous post that we identified one very visible issue with the on-demand installation of software when using YaST (containerized or not) in a transactional system like the future ALP. Such systems prevent the installation of new packages during run-time, so an extra reboot is always needed before using the new software.

We explored several options to make YaST work as smooth as possible in transactional systems, like performing all the modifications, including packages installation and configuration changes, in a single transaction with a final reboot at the end of the process. But we found it too risky since it implies working on temporary system snapshots that are not a fully accurate representation of how the managed system will look after the reboot.

Finally we implemented the solution that is shown in the screenshot below. For the time being, if YaST detects it’s running in a transactional system so it cannot install the missing packages and continue, then it will simply ask the user to install the packages and reboot.

With that, YaST does not longer look broken on transactional systems (unsuccessfully trying to install packages when it doesn’t make sense) but the adopted solution is just a first approach that we will likely improve in the future.

Beyond YaST: On-Demand Installation on Transactional ALP

The described challenge with package management and transactional systems is not exclusive of YaST. We actually have a similar problem with Cockpit and its metrics functionality. So we decided we needed to gather some opinions to find the most adequate and consistent solution for ALP and other transactional systems.

As starting point, we wrote this document describing the situation and presenting some open questions. The feedback gathered so far from members of the ALP Steering Committee suggests we should improve YaST to go further into assisting the user in the process of installing the packages and rebooting the transactional system. The same applies to Cockpit, but that may be more problematic since it’s not aligned with the current vision expressed by the Cockpit developers in that regard.

We are always open to receive more comments and opinions. If you have any, you know how to reach us. ;-)

Better Cockpit Metrics on ALP

And talking about the metrics functionality of Cockpit, we also took the opportunity to polish its

behavior on ALP. And we did it by fixing nothing ourselves. :-) We just diagnosed the problems and

reported what was wrong in the pcp package

and in Cockpit. Both issues are fixed

now by their corresponding maintainers and future ALP pre-releases will offer a more pleasant

Cockpit experience out-of-the-box.

See You Soon

We keep working on YaST, especially on the installer security policies described on our previous report, on improving the Cockpit and the YaST user experiences with ALP and on several other topics we will report in the following weeks, as soon as we have tangible results to show.

Meanwhile we encourage you to get involved in openSUSE development and promotion and to stay tuned for more news. Have a lot of fun!

openSUSE in 2022 | Continues to be Awesome

openSUSE Tumbleweed – Review of the week 2022/35

Dear Tumbleweed users and hackers,

We all knew the day would come – and after 26 daily snapshots were released, 0830 wanted to break that. It turned out that libxml 2.10.x is not entirely ABI compatible with the previous 2.9.x we had in the tree (depending on configure parameters given; IMHO such symbols should have a specific version for those options, allowing to require feature sets). Snapshot 0831 is a very large one: as we checked in glibc during this week, coupled with this ABI break, we decided to let OBS decide what all needs a rebuild (with glibc which usually is everything). In total, we released 5 snapshots this week (0826, 0827, 0828, 0829, and 0831).

The most relevant changes in these snapshots were:

- Meson 0.63.1

- Shadow 4.12.3

- Grub2: revert to a version from 2 months ago without the various TPM patches: they turned out to cause a lot of trouble (and are being further reworked in the devel project)

- Mozilla Firefox 104.0

- Mozilla Thunderbird 102.2

- glibc 2.36

- Make: Add support for job server using named pipes

The staging projects are testing these upgrades and changes:

- Linux kernel 5.19.6

- util-linux 2.38.1: this also brings a massive package layout change, which will probably take some time to settle. It’s part of the distro bootstrap and we have to be careful to not blow it out of proportion

- Mozilla Thunderbird 102.2.1

- GCC 12.2

- fmt 9.0: Breaks ceph and zxing-cpp

- libxml 2.10.2: breaks xmlsec1

- gpgme 1.18: breaks libreoffice

- libxslt 1.1.36: breaks daps

Tumbleweed Continues Release Streak

Tumbleweed’s continuous daily release streak has reached an astounding 26 snapshots.

The streak of openSUSE’s rolling release continued this week and packages like glibc, ibus, Mozilla Firefox and sudo all received updates.

Will the streak continue beyond snapshot 20220829? Users should know soon.

Snapshot 20220829 provided package updates for AppArmor and libapparmor3.0.7. The new versions fixed the setuptools-version detection in buildpath.py. The Man pages for Japanese made some improvements with the man-pages-ja 20220815 update. The tree 2.0.3 update provided multiple fixes for .gitignore functionality and fixed a couple segfaults.

The 20220828 snapshot had ten packages updated. Among the updated packages were ibus 1.5.27, which enabled an ibus restart in GNOME desktop and disabled XKB engines in Plasma Wayland. The update of webkit2gtk3 2.36.7 fixed several crashes and rendering issues as well as addressed a Common Vulnerabilities and Exposure related to Apple’s use of the package. The Python web framework and asynchronous networking library python-tornado6 6.2 enabled SSL certificate verification and hostname checks by default and its Continuous Integration has moved from Travis and Appveyor to Github Actions. Another package to update in the snapshot was font handler libXfont2 2.0.6. The new version fixed some spelling and wording issues. It also fix comments to reflect the removal of legacy Operating System/2 support.

A new major version of the Mozilla Firefox browser arrived in snapshot 20220827. Firefox 104.0 addressed multiple CVEs to include an address bar spoofing to disguise a URL; another fixed an exploit that showed evidence of memory corruption and the possibility to running arbitrary code. The update of the GNU C Library added major new features; glibc 2.36 added process_madvise and process_mrelease functions. Support for the DT_RELR relocation format was added and socket connection fsopen and many other sorting features were added. VMware’s open-vm-tools 12.1.0 package, which enables several features to better manage seamless user interactions with guests, fixed a vulnerability that allowed for local privilege escalation; it also had a fix for the build of the ContainerInfo plugin for a 32-bit Linux release. A few RubyGems like rubygem-faraday-net_http 3.0.0, rubygem-parser 3.1.2.1 and rubygem-rubocop 1.35.1 were also updated in the snapshot.

A total of three packages were updated in snapshot 20220826. The simple PIN- or passphrase-secure reader pinentry updated to 1.2.1; the package improved accessibility and fixed the handling of an error during initialization. The package update also made sure an entered PIN is always cleared from memory. Its graphical user interface pinentry-gui was also updated to the 1.2.1 version. The shadow package, which converts UNIX password files to the shadow password format, updated to version 4.12.3. It fixed a 9-year-old CVE. CVE-2013-4235 fixed the time-of-check time-of-use race condition when copying and removing directory trees. The package also updated and fixed some Spanish and French translations.

A minor update to sudo 1.9.11p3 arrived in snapshot 20220825. The update fixed a crash in the Python module with Python 3.9.10 on some systems and AppArmor integration was made available for Linux, so a sudoers rule can now specify an APPARMOR_PROFILE option to run a command confined by the named AppArmor profile. The sudo package also fixed a regression introduced in 1.9.11p1 that caused a warning when logging to sudo_logsrvd if the command returned no output. That regression was never released in a Tumbleweed snapshot. An update of the open-source disk encryption package cryptsetup updated to 2.5.0. This new version removed cryptsetup-reencrypt tool from the project and move reencryption to an already existing cryptsetup reencrypt command. Other packages to update in the snapshot were gnome-bluetooth 42.3, device memory enabler ndctl 74, yast2-tune 4.5.1 and more.

Member

Member DimStar

DimStar