क्या openSUSE Asia Summit 2020 अब भी भारत में होगा ?

इस प्रश्न का उत्तर जानने के लिए हमें जुलाई के महीने तक इंतजार करना होगा।

१७ मार्च को openSUSE Board की बैठक हुई। यह निर्णय लिया गया कि इस समय हम केवल COVID-19 की स्थिति देख सकते हैं और जुलाई तक इंतजार कर सकते हैं जब बोर्ड द्वारा openSUSE.Asia Summit और oSLO 2020 को लेकर कुछ निर्णय लिया जाएगा।

तब तक सुरक्षित रहें और यदि आप का देश लॉकडाउन में हैं तो कृपया घर पर रहें।

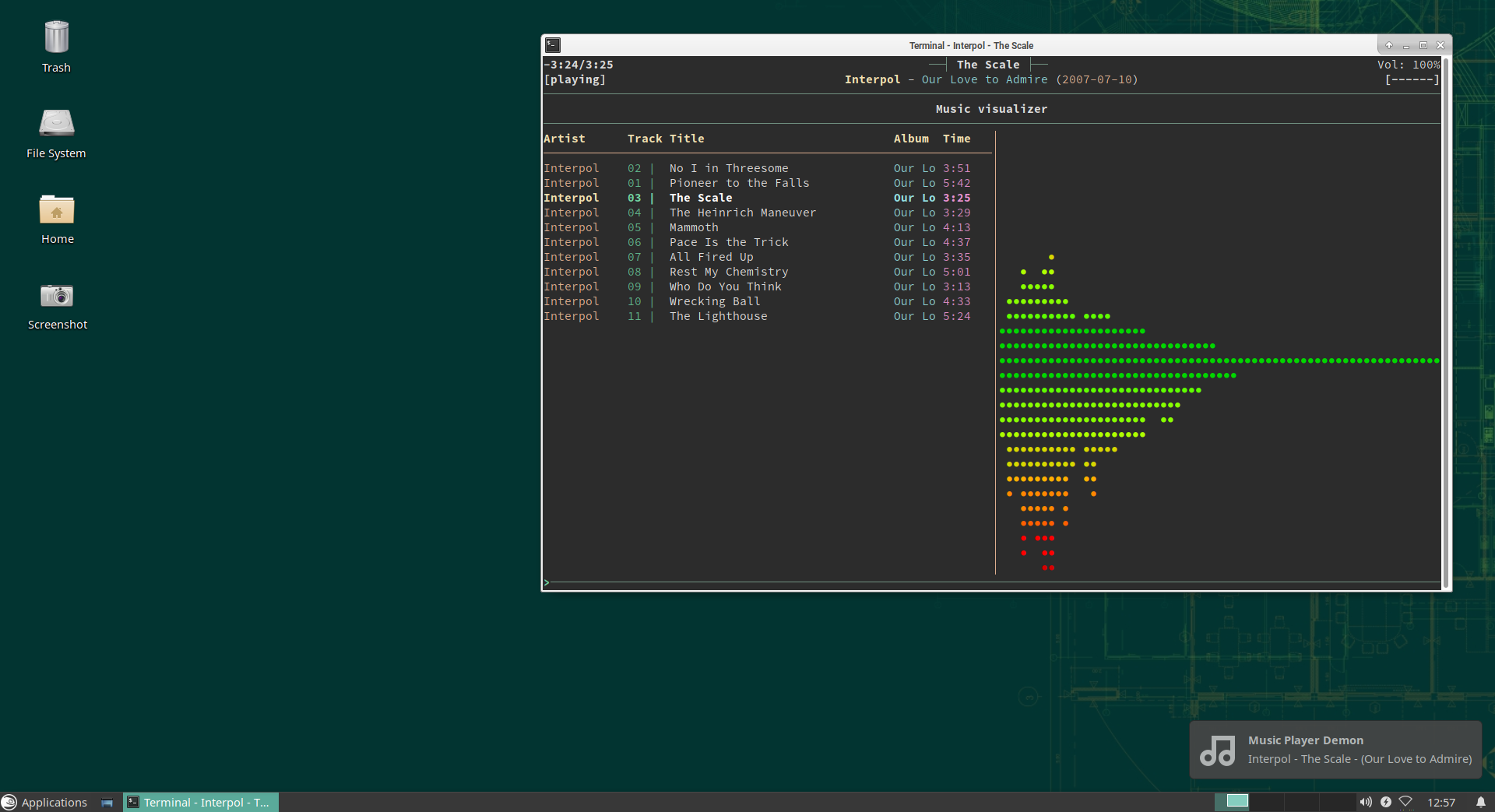

Listen to your music with mpd and ncmpcpp

In this article, we will discover a softwares trio that will allow you to manage and listen to your music from your terminal:

- mpd: the music player daemon

- mpc: a CLI interface to mpd

- ncmpcpp: a mpd client, written in C++ with a ncurses interface

We will see how to install, configure and use it, as well as configuring smoothly integrated desktop notifications.

Installation

As they are available in the official openSUSE repositories installing them is as easy as:

zypper in mpd mpclient ncmpcpp

Onward to the configuration part !

Configuring mpd, the music player daemon

In this article, we will configure and run mpd as an user instance. If needed, it can of course run as a system instance. In that case, you should configure it in /etc/mpd.conf.

First of all, let’s create some configuration directories:

mkdir ~/.config/mpd

mkdir ~/.config/mpd/playlists

Then, we will use the package template:

cp /usr/share/doc/packages/mpd/mpdconf.example ~/.config/mpd/mpd.conf

and edit it to our needs. Below is an extract of the important settings (the example user is geeko):

grep -v "^#|^$" ~/.config/mpd/mpd.conf

music_directory "~/Music"

playlist_directory "~/.config/mpd/playlists"

db_file "~/.config/mpd/mpd.db"

log_file "~/.config/mpd/log"

pid_file "~/.config/mpd/mpd.pid"

state_file "~/.config/mpd/mpdstate"

sticker_file "~/.config/mpd/sticker.sql"

user "geeko"

bind_to_address "localhost"

port "6600"

log_level "default"

restore_paused "yes"

input {

plugin "curl"

}

audio_output {

type "pulse"

name "Pulse MPD Output"

}

audio_output {

type "fifo"

name "mpd_fifo"

path "/tmp/mpd.fifo"

format "44100:16:2"

}

filesystem_charset "UTF-8"

It is crucial to set properly the path to your audio files and sound output. Here we use PulseAudio as it is installed and used by default on most openSUSE desktops. If you are attentive, you will notice that we added a second audio output which will not be used for audio but to display a graphical visualizer in ncmpcpp (yes, in a terminal emulator !).

Activate mpd as an user space systemd service

Now we will create a systemd service that will start mpd with the user settings. This way mpd will start with your session.

Let’s create the needed directories structure:

mkdir -p ~/.config/systemd/user

and create the service file:

$EDITOR ~/.config/systemd/user/mpd.service

add the following content (remember to adapt the $USER variable to your need):

[Unit]

Description=Music Player Daemon

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/bin/mpd --no-daemon /home/$USER/.config/mpd/mpd.conf

ExecStop=/usr/bin/mpd --kill

PIDFile=/home/$USER/.config/mpd/mpd.pid

[Install]

WantedBy=default.target

finally, let’s start and enable this service:

systemctl --user start mpd

systemctl --user enable mpd

ncmpcpp’s configuration

Now that mpd is up and running, we will configure the ncurses client we installed : ncmpcpp.

mkdir ~/.ncmpcpp

cp /usr/share/doc/packages/ncmpcpp/config ~/.ncmpcpp/

$EDITOR ~/.ncmpcpp/config

Here is an example of a nice colorized configuration with a split view:

grep -v "^#|^$" ~/.ncmpcpp/config

ncmpcpp_directory = ~/.ncmpcpp

lyrics_directory = ~/.ncmpcpp/lyrics

mpd_host = localhost

mpd_port = 6600

mpd_connection_timeout = 5

mpd_music_dir = ~/Music

mpd_crossfade_time = 5

visualizer_fifo_path = /tmp/mpd.fifo

visualizer_output_name = mpd_fifo

visualizer_in_stereo = yes

visualizer_sync_interval = 30

visualizer_type = ellipse

visualizer_look = ▮●

visualizer_color = 41, 83, 119, 155, 185, 215, 209, 203, 197, 161

system_encoding = "UTF-8"

playlist_disable_highlight_delay = 5

message_delay_time = 5

song_list_format = {%a - }{%t}|{$8%f$9}$R{$3(%l)$9}

song_status_format = {{%a{ "%b"{ (%y)}} - }{%t}}|{%f}

song_library_format = {%n - }{%t}|{%f}

alternative_header_first_line_format = $b$1$aqqu$/a$9 {%t}|{%f} $1$atqq$/a$9$/b

alternative_header_second_line_format = {{$4$b%a$/b$9}{ - $7%b$9}{ ($4%y$9)}}|{%D}

now_playing_prefix = $b

now_playing_suffix = $/b

song_window_title_format = {%a - }{%t}|{%f}

browser_sort_mode = name

browser_sort_format = {%a - }{%t}|{%f} {(%l)}

song_columns_list_format = (20)[]{a} (6f)[green]{NE} (50)[white]{t|f:Title} (20)[cyan]{b} (7f)[magenta]{l}

playlist_show_mpd_host = no

playlist_show_remaining_time = yes

playlist_shorten_total_times = no

playlist_separate_albums = no

playlist_display_mode = columns

browser_display_mode = classic

search_engine_display_mode = classic

playlist_editor_display_mode = classic

incremental_seeking = yes

seek_time = 1

volume_change_step = 2

autocenter_mode = yes

centered_cursor = yes

progressbar_look = =>

default_place_to_search_in = database

user_interface = alternative

media_library_primary_tag = genre

default_find_mode = wrapped

header_visibility = yes

statusbar_visibility = yes

titles_visibility = yes

header_text_scrolling = yes

cyclic_scrolling = yes

lines_scrolled = 2

follow_now_playing_lyrics = yes

fetch_lyrics_for_current_song_in_background = yes

store_lyrics_in_song_dir = yes

allow_for_physical_item_deletion = no

screen_switcher_mode = browser, media_library, visualizer

startup_screen = playlist

startup_slave_screen = "visualizer"

startup_slave_screen_focus = no

locked_screen_width_part = 50

jump_to_now_playing_song_at_start = yes

ask_before_clearing_playlists = yes

clock_display_seconds = no

display_volume_level = yes

display_bitrate = no

display_remaining_time = yes

ignore_leading_the = no

mouse_support = yes

enable_window_title = yes

external_editor = vim

use_console_editor = yes

colors_enabled = yes

With these settings you will have a split view with the current playlist of the left and the visualizer on the right. All options are well documented in ncmpcpp’s man page.

Use it

Here are a few shortcuts that will help you getting started

- F1 : show help

- 1 : show playlist ;

- 2 : show directory browser

- 3 : show search

- 4 : show library

- 5 : playlist editor

- 6 : tags editor

- 8 : visualizer

- p : toggle play/pause

- a : add selection to playlist

- > : play next track

- < :play previous track

Desktop Environment shortcut

By default, pressing p will toggle pause, but what if you are not in front of your terminal running ncmpcpp ? That is where mpc enters the game. Let’s open our favorite desktop environment settings and add some keyboard shortcuts:

- MPD Pause: use the

mpc togglecommand - MPD Previous Song: use the

mpc prevcommand - MPD Next Song: use the

mpc nextcommand

Extra: get notified when song changes

There is a configuration parameter in ncmpcpp that makes it trigger a command each time the song changes, we will use it to execute a small Python3 script in order to pop a nice desktop notification.

In order to use this script, you will have to make sure that two small libs are installed:

zypper in python3-notify2 python3-python-mpd2

Then add the following code in a file called mpd_notify.py in your $HOME/bin:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF8 -*-

import gi

import notify2

from gi.repository import GLib

from mpd import MPDClient

client = MPDClient()

client.timeout = 10

client.idletimeout = None

client.connect("localhost", 6600)

mpd_song = MPDClient.currentsong(client)

s_artist = mpd_song['artist']

s_title = mpd_song['title']

s_album = mpd_song['album']

s_notification = s_artist + " - " + s_title + " - (" + s_album +")"

notify2.init("Music Player Demon")

show_song = notify2.Notification("Music Player Demon", s_notification,

icon="/usr/share/icons/Adwaita/scalable/emblems/emblem-music-symbolic.svg")

show_song.set_hint("transient", True)

show_song.show()

Now, we will just add the corresponding parameter in ncmpcpp configuration’s file:

execute_on_song_change = "/usr/bin/python3 /home/$USER/bin/mpd_notify.py"

In the end

We hope that you liked this discovery and that you will enjoy managing your music with those tools. ncmpcpp is quite powerful, it includes search capabilities, different views of your music library, a tag editor and everything you need to tweak it to your taste !

openSUSE Tumbleweed – Review of the week 2020/13

Dear Tumbleweed users and hackers,

During this week, we have released 6 snapshots to the public (0318, 0319, 0320, 0322, 0324, 0325). The changes were more under the hood than spectacular, but here they are:

- RPM: change of database format to ndb (Read on – there were some issues)

- Mozilla Firefox 74.0

- Linux kernel 5.5.9 & 5.5.11

- VirtualBox 6.1.4

- KDE Frameworks 5.68.0

- Mesa 20.0.2

- Coreutils 8.32

- Samba 4.12.0

This was week 13. Are you superstitious? Any special fear of ’13’? We could, of course, blame week 13 for the minor issue we had not caught with openQA, but I’d rather claim it would have happened any week. We simply lack an upgrade test for MicroOS. What am I talking about? You most likely have not even realized there was an issue. The RPM switch of the database format to ndb (any other DB format would have exposed the same issue, so no flaming here) had a glitch on MicroOS and transactional-update based installations in that the RPM database was not accessible for a moment. Nothing broke (unless you rolled back after seeing it – this might have been more problematic). See Bug 1167537 if you’re interested in more details. Of course, fixed RPM packages are already out (we even published it asap in the :Update channel) – and the affected systems could self heal.

Staging projects are still busy with changes around these topics:

- Kubernetes 1.18.0

- Linux kernel 5.5.13

- Rust 1.41.1

- LLVM 10

- Qt 5.15.0 (currently beta2 being tested)

- Ruby 2.7 – possibly paired with the removal of Ruby 2.6

- GCC 10 as the default compiler

- Removal of Python 2

- GNU Make 4.3

Manage your dotfiles with Git

Dot what ???

What is commonly referred to as dotfiles are all those small plain text files that contain your softwares’ configuration. Most of the time they reside in your $HOME directory but are hidden as they are prefixed with a dot, hence their name. For some apps, you can find them as well in the $HOME/.config directory.

When it comes to managing them (i.e keep track of the changes, moving them around between different workstations, backing them up,…), there are different solutions:

- the good old USB stick

- rsyncing them

- syncing them in the “cloud”

- copying them in a central folder and symlinking them to where they are supposed to be found

In this article, we will focus on how to manage them in an efficient and simple way with Git.

Git comes to rescue

In this example, we will use $HOME/Dotfiles as the Git repository, but feel free to change it to your needs.

First of all, we will initialize this repository

git init --bare $HOME/Dotfiles

Then, as all the git commands that we will use will refer to this repository, it is advised to create an alias, such as:

alias dotfiles='/usr/bin/git --git-dir=$HOME/Dotfiles --work-tree=$HOME'

You can add this line to your $SHELL configuration file ($HOME/.bashrc if you use Bash or $HOME/.zshrc if you use zsh).

Next, we will configure Git so it will not show all the untracked files. This is required as we use the entire $HOME as work tree.

dotfiles config --local status.showUntrackedFiles no

At that point, you should be able to check the state of this repository:

dotfiles status

Then you can add your configuration files and commit as you wish. For example, let’s add our .bashrc :

dotfiles add .bashrc

dotfiles commit -m "Added .bashrc"

Now just add a remote repository (your self-hosted Git or a public one) and push your changes to it:

dotfiles remote add origin git@yourgit.example.com/dotfiles.git

dotfiles push

Setup a new machine

Now that you have it all set, let’s configure a new system with the dotfiles you have in your repository.

First, clone locally your online repository:

git clone --bare git@yourgit.example.com/dotfiles.git $HOME/Dotfiles

Again, you have to defined the same alias as before:

alias dotfiles='/usr/bin/git --git-dir=$HOME/Dotfiles --work-tree=$HOME'

Remember to put it in your $SHELL configuration file. Now, just apply the changes from the repository you have just cloned to your system:

dotfiles checkout

If some of the files already exist, you will get an error. This will probably happen with files created by default during the openSUSE installation and user account creation, such as the $HOME/.bashrc file, no worries, just rename or delete them.

Now, each time you change your configuration files tracked by Git, remember to commit and push your changes.

Sources

The following articles where used as sources of this article. Thanks a lot to their authors:

Reducing memory consumption in librsvg, part 4: compact representation for Bézier paths

Let's continue with the enormous SVG from the last time, a map extracted from OpenStreetMap.

According to Massif, peak memory consumption for that file occurs at the following point during the execution of rsvg-convert. I pasted only the part that refers to Bézier paths:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n time(i) total(B) useful-heap(B) extra-heap(B) stacks(B)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 33 24,139,598,653 1,416,831,176 1,329,943,212 86,887,964 0

2 ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: alloc (alloc.rs:84)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: alloc (alloc.rs:172)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: allocate_in<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand,alloc::alloc::Global> (raw_vec.rs:98)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: with_capacity<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand> (raw_vec.rs:167)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: with_capacity<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand> (vec.rs:358)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x4A2727E: <alloc::vec::Vec<T> as alloc::vec::SpecExtend<T,I>>::from_iter (vec.rs:1992)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x49D212C: from_iter<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand,smallvec::IntoIter<[rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand; 32]>> (vec.rs:1901)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x49D212C: collect<smallvec::IntoIter<[rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand; 32]>,alloc::vec::Vec<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand>> (iterator.rs:1493)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x49D212C: into_vec<[rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand; 32]> (lib.rs:893)

| ->24.88% (352,523,448B) 0x49D212C: smallvec::SmallVec<A>::into_boxed_slice (lib.rs:902)

3 | ->24.88% (352,523,016B) 0x4A0394C: into_path (path_builder.rs:320)

|

4 ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A242F0: realloc (alloc.rs:128)

| ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A242F0: realloc (alloc.rs:187)

| ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A242F0: shrink_to_fit<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand,alloc::alloc::Global> (raw_vec.rs:633)

| ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A242F0: shrink_to_fit<rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathCommand> (vec.rs:623)

| ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A242F0: alloc::vec::Vec<T>::into_boxed_slice (vec.rs:679)

| ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x49D2136: smallvec::SmallVec<A>::into_boxed_slice (lib.rs:902)

5 | ->03.60% (50,990,328B) 0x4A0394C: into_path (path_builder.rs:320)

Line 1 has the totals, and we see that at that point the program uses 1,329,943,212 bytes on the heap.

Lines 3 and 5 give us a hint that into_path is being called; this is

the function that converts a temporary/mutable PathBuilder into a

permanent/immutable Path.

Lines 2 and 4 indicate that the arrays of PathCommand, which are

inside those immutable Paths, use 24.88% + 3.60% = 28.48% of the

program's memory; between both they use

352,523,448 + 50,990,328 = 403,513,776 bytes.

That is about 400 MB of PathCommand. Let's see what's going on.

What is in a PathCommand?

A Path is a list of commands similar to PostScript, which get used

in SVG to draw Bézier paths. It is a flat array of PathCommand:

pub struct Path {

path_commands: Box<[PathCommand]>,

}

pub enum PathCommand {

MoveTo(f64, f64),

LineTo(f64, f64),

CurveTo(CubicBezierCurve),

Arc(EllipticalArc),

ClosePath,

}

Let's see the variants of PathCommand:

-

MoveTo: 2 double-precision floating-point numbers. -

LineTo: same. -

CurveTo: 6 double-precision floating-point numbers. -

EllipticalArc: 7 double-precision floating-point numbers, plus 2 flags (see below). -

ClosePath: no extra data.

These variants vary a lot in terms of size, and each element of the

Path.path_commands array occupies the maximum of their sizes

(i.e. sizeof::<EllipticalArc>).

A more compact representation

Ideally, each command in the array would only occupy as much space as it needs.

We can represent a Path in a different way, as two separate arrays:

- A very compact array of commands without coordinates.

- An array with coordinates only.

That is, the following:

pub struct Path {

commands: Box<[PackedCommand]>,

coords: Box<[f64]>,

}

The coords array is obvious; it is just a flat array with all the

coordinates in the Path in the order in which they appear.

And the commands array?

PackedCommand

We saw above that the biggest variant in PathCommand is

Arc(EllipticalArc). Let's look inside it:

pub struct EllipticalArc {

pub r: (f64, f64),

pub x_axis_rotation: f64,

pub large_arc: LargeArc,

pub sweep: Sweep,

pub from: (f64, f64),

pub to: (f64, f64),

}

There are 7 f64 floating-point numbers there. The other two fields,

large_arc and sweep, are effectively booleans (they are just enums

with two variants, with pretty names instead of just true and

false).

Thus, we have 7 doubles and two flags. Between the two flags there are 4 possibilities.

Since no other PathCommand variant has flags, we can have the

following enum, which fits in a single byte:

#[repr(u8)]

enum PackedCommand {

MoveTo,

LineTo,

CurveTo,

ArcSmallNegative,

ArcSmallPositive,

ArcLargeNegative,

ArcLargePositive,

ClosePath,

}

That is, simple values for MoveTo/etc. and four special values for

the different types of Arc.

Packing a PathCommand into a PackedCommand

In order to pack the array of PathCommand, we must first know how

many coordinates each of its variants will produce:

impl PathCommand {

fn num_coordinates(&self) -> usize {

match *self {

PathCommand::MoveTo(..) => 2,

PathCommand::LineTo(..) => 2,

PathCommand::CurveTo(_) => 6,

PathCommand::Arc(_) => 7,

PathCommand::ClosePath => 0,

}

}

}

Then, we need to convert each PathCommand into a PackedCommand and

write its coordinates into an array:

impl PathCommand {

fn to_packed(&self, coords: &mut [f64]) -> PackedCommand {

match *self {

PathCommand::MoveTo(x, y) => {

coords[0] = x;

coords[1] = y;

PackedCommand::MoveTo

}

// etc. for the other simple commands

PathCommand::Arc(ref a) => a.to_packed_and_coords(coords),

}

}

}

Let's look at that to_packed_and_coords more closely:

impl EllipticalArc {

fn to_packed_and_coords(&self, coords: &mut [f64]) -> PackedCommand {

coords[0] = self.r.0;

coords[1] = self.r.1;

coords[2] = self.x_axis_rotation;

coords[3] = self.from.0;

coords[4] = self.from.1;

coords[5] = self.to.0;

coords[6] = self.to.1;

match (self.large_arc, self.sweep) {

(LargeArc(false), Sweep::Negative) => PackedCommand::ArcSmallNegative,

(LargeArc(false), Sweep::Positive) => PackedCommand::ArcSmallPositive,

(LargeArc(true), Sweep::Negative) => PackedCommand::ArcLargeNegative,

(LargeArc(true), Sweep::Positive) => PackedCommand::ArcLargePositive,

}

}

}

Creating the compact Path

Let's look at PathBuilder::into_path line by line:

impl PathBuilder {

pub fn into_path(self) -> Path {

let num_commands = self.path_commands.len();

let num_coords = self

.path_commands

.iter()

.fold(0, |acc, cmd| acc + cmd.num_coordinates());

First we compute the total number of coordinates using fold; we ask

each command cmd its num_coordinates() and add it into the acc

accumulator.

Now we know how much memory to allocate:

let mut packed_commands = Vec::with_capacity(num_commands);

let mut coords = vec![0.0; num_coords];

We use Vec::with_capacity to allocate exactly as much memory as we will

need for the packed_commands; adding elements will not need a

realloc(), since we already know how many elements we will have.

We use the vec! macro to create an array of 0.0 repeated

num_coords times; that macro uses with_capacity internally. That is the

array we will use to store the coordinates for all the commands.

let mut coords_slice = coords.as_mut_slice();

We get a mutable slice out of the whole array of coordinates.

for c in self.path_commands {

let n = c.num_coordinates();

packed_commands.push(c.to_packed(coords_slice.get_mut(0..n).unwrap()));

coords_slice = &mut coords_slice[n..];

}

For each command, we see how many coordinates it will generate and we

put that number in n. We get a mutable sub-slice from

coords_slice with only that number of elements, and pass it to

to_packed for each command.

At the end of each iteration we move the mutable slice to where the next command's coordinates will go.

Path {

commands: packed_commands.into_boxed_slice(),

coords: coords.into_boxed_slice(),

}

}

At the end, we create the final and immutable Path by converting

each array into_boxed_slice like the last time. That way each of

the two arrays, the one with PackedCommands and the one with

coordinates, occupy the minimum space they need.

An iterator for Path

This is all very well, but we also want it to be easy to iterate on

that compact representation; the PathCommand enums from the

beginning are very convenient to use and that's what the rest of the

code already uses. Let's make an iterator that unpacks what is inside

a Path and produces a PathCommand for each element.

pub struct PathIter<'a> {

commands: slice::Iter<'a, PackedCommand>,

coords: &'a [f64],

}

We need an iterator over the array of PackedCommand so we can visit

each command. However, to get elements of coords, I am going to

use a slice of f64 instead of an iterator.

Let's look at the implementation of the iterator:

impl<'a> Iterator for PathIter<'a> {

type Item = PathCommand;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> {

if let Some(cmd) = self.commands.next() {

let cmd = PathCommand::from_packed(cmd, self.coords);

let num_coords = cmd.num_coordinates();

self.coords = &self.coords[num_coords..];

Some(cmd)

} else {

None

}

}

}

Since we want each iteration to produce a PathCommand, we declare it

as having the associated type Item = PathCommand.

If the self.commands iterator has another element, it means there is

another PackedCommand available.

We call PathCommand::from_packed with the self.coords slice to

unpack a command and its coordinates. We see how many coordinates the

command consumed and re-slice self.coords according to the number of

commands, so that it now points to the coordinates for the next

command.

We return Some(cmd) if there was an element, or None if the

iterator is empty.

The implementation of from_packed is obvious and I'll just paste a

bit from it:

impl PathCommand {

fn from_packed(packed: &PackedCommand, coords: &[f64]) -> PathCommand {

match *packed {

PackedCommand::MoveTo => {

let x = coords[0];

let y = coords[1];

PathCommand::MoveTo(x, y)

}

// etc. for the other variants in PackedCommand

PackedCommand::ArcSmallNegative => PathCommand::Arc(EllipticalArc::from_coords(

LargeArc(false),

Sweep::Negative,

coords,

)),

PackedCommand::ArcSmallPositive => // etc.

PackedCommand::ArcLargeNegative => // etc.

PackedCommand::ArcLargePositive => // etc.

}

}

}

Results

Before the changes (this is the same Massif heading as above):

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n time(i) total(B) useful-heap(B) extra-heap(B) stacks(B)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

33 24,139,598,653 1,416,831,176 1,329,943,212 86,887,964 0

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

boo

After:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n time(i) total(B) useful-heap(B) extra-heap(B) stacks(B)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

28 26,611,886,993 1,093,747,888 1,023,147,907 70,599,981 0

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

oh yeah

We went from using 1,329,943,212 bytes down to 1,023,147,907 bytes, that is, we knocked it down by 300 MB.

However, that is for the whole program. Above we saw that Path data

occupies 403,513,776 bytes; how about now?

->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: alloc (alloc.rs:84)

| ->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: alloc (alloc.rs:172)

| ->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: allocate_in<f64,alloc::alloc::Global> (raw_vec.rs:98)

| ->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: with_capacity<f64> (raw_vec.rs:167)

| ->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: with_capacity<f64> (vec.rs:358)

| ->07.45% (81,525,328B) 0x4A34C6F: rsvg_internals::path_builder::PathBuilder::into_path (path_builder.rs:486)

Perfect. We went from occupying 403,513,776 bytes to just

81,525,328 bytes. Instead of Path data amounting to 28.48% of the

heap, it is just 7.45%.

I think we can stop worrying about Path data for now. I like how

this turned out without having to use unsafe.

References

Kismet, Frameworks Updates Land in openSUSE Tumbleweed

Four openSUSE Tumbleweed snapshots were released so far this week.

Kismet, KDE Frameworks, sudo, LibreOffice and ImageMagick were just a few of the packages that received updates in the snapshots.

The most recent snapshot, 20200322 brougth the 1.3.6 version of the Bluetooth configuration tool, blueberry. Full featured Command Line Interface (CLI) system information tool inxi 3.0.38 fixed a Perl issue where perl treats 000 as a string and not 0. General purpose VPN package WireGuard removed dead code. The snapshot also updated several YaST packages. Fixes were made to help with text icons displayed during installations in yast2 4.2.74 package and some cosmetic changes were made in the yast2-ntp-client 4.2.10 package to not show check-boxes for saving configuration and starting the deamon. The snapshot is currently trending at a rating of 84, according to the Tumbleweed snapshot reviewer.

Just three packages were updated in snapshot 20200320. Python 2 compatibility was removed in the urlscan 0.9.4 package. Both elementary-xfce-icon-theme and perl-Encode 3.05 were updated in the snapshot, which is trending at a rating of 99.

The other two snapshots also recorded a stable rating of 99.

ImageMagick 7.0.10.0 provided an update that prevent heap overflow in snapshot 20200319. KDE’s Frameworks 5.68.0 fixed a memory leak in ConfigView and Dialog. Multiple additions and fixes were made to the Breeze Icons package of the new Frameworks version and Kirigami improved support Qt 5.14 on Android. LibreOffice 6.4.2.2 brought some translations and sudo had a minor change regarding an update that affected Linux containers and ignored a failure to restore the to RLIMIT_CORE resource limit.

Both the GNU Compiler Collection 9 and 10 were updated in the 20200318 snapshot. The updated versions includes fixes for binutils version parsing. The new major version of Mozilla Firefox 74.0 landed in the snapshot and fixed a dozen Common Vulnerability and Exposures, which included a fix for CVE-2020-6809 that addressed the Web Extensions that had the all-urls permission and made a fetch request with a mode set to ‘same-origin’ possible for the Web Extension to read local files. The Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (alsa) 1.2.2 package added multiple patches and the same version alsa-plugins package provided an update for m4 files affecting macro processors. Apparmor 2.13.4 provided several abstraction updates and fixed log parsing for logs with an embedded newline. Developers will be happy to see a new cscope 15.9 for source code searches as it adds parentheses and vertical bar metacharacters in regex searches. SecureTransport and WinCrypt implementations for sha256 were added in the curl 7.69.1. A maintenance release for virtualbox 6.1.4 was in the snapshot; the update supports Linux Kernel 5.5. Linux Kernel 5.5.9 was also released in the snapshot and xfsprogs 5.5.0 fixed broken unit conversions in the xfs_repair. Wireless network and device detector, sniffer, wardriving tool Kismet had its first full release for 2020, which was primarily a bugfix release; the 2020_03_R1 version had a fix for buffer size calculations, which could impact gps handling, and had updates for the ultra-low-power, highly-integrated single-chip device kw41z capture code.

Windows 10 update error 0x800f0922

A Thinkpad of mine that has Windows 10 co-installed was refusing all cumulative Windows updates since about 6 months, always performing everything, rebooting, counting up to 99%, then failing with error 0x800f0922 and rolling back.

Now this Windows instance is not really used and thus not booted on a regular base, but I'd still rather keep it up to date in case I somewhen really need it for something.

So I searched the internet for error 0x800f0922... and tried almost everything that was mentioned as a possible fix:

- resetting windows update

- uninstalling various pieces of software

- in general, random changing of different settings ;-)

ownCloud unterstützt Musikunterricht

Im letzten Beitrag wurde die Idee zu einem auf der verbreiteten privaten Cloud Infrastruktur ownCloud basierenden System zum Unterricht erläutert, wenn die persönliche Begegnung wie zur Zeit nicht möglich ist.

Um das noch etwas zugänglicher zu machen, haben wir ein Video erstellt, das die Interaktion zwischen einer Musiklehrerin und ihrer Schülerin Felizitas beispielhaft zeigt. Dabei werden Videos geteilt, die einen eingeschränkten Lehrbetrieb ermöglichen und die Schülerin bei der Sache hält.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QygiyNrvQXc

Die beschriebenen Schritte lassen sich ohne weiteres sofort mit jeder ownCloud oder wohl auch Nextcloud durchführen. Dabei können trotz der besonderen Situation Datenschutzaspekte beachtet werden.

Hoffentlich trägt das dazu bei, dass ohne lange Verzögerung das Beste aus der Situation gemacht werden kann.

The ultimate DIY guide for installing WordPress on openSUSE Tumbleweed

I am preparing a new WordPress website (Architect2Succeed.com) which is aimed at my profession as an IT architect.

When I setup Fossadventures.com, I didn’t make an installation instruction as I was not sure that everything would be as I liked. Which turned out to be true, as I have switched from Hack/HHVM to PHP7/PHP-FPM.

In this tutorial I want to incorporate all the learnings from my previous experience. This tutorial is likely to be very beneficial for all Linux beginners, who want to install WordPress from scratch on a VPS server running openSUSE Tumbleweed.

This Complete DIY guide is based on learnings from other great tutorials. See reference list below. I like to send out a huge thanks to the writers of these tutorials. I have combined their learnings and added some of my own.

- HowtoForge (LEMP tutorial) (WordPress tutorial)

- Rosehosting (LEMP tutorial) (WordPress tutorial)

- Linuxbabe (LEMP tutorial) (WordPress tutorial)

- Bjorn Johansen (Block PHP files)

- DigitalOcean (Increase PageSpeed Score)

- openSUSE.org (Let’s Encrypt)

Get your Virtual Private Server ready

The first thing to do is to purchase an openSUSE VPS. There are various options available. However, not all of them document the openSUSE version that they offer, which is a big miss in my opinion. Prices do vary, which means that you have to think about where these organizations have cut corners. Personally, I went with Transip.nl. But I feel that Linode would also be a good option.

- VPSserver.com – offers an openSUSE ??? VPS with 25GB disk for € 5 / month

- Transip.nl – offers a Tumbleweed VPS with 50GB SSD for € 10 / month

- Linode.com – offers an openSUSE Leap 15.1 VPS with 50GB SSD for € 10 / month

- Rosehosting.com – offers a managed openSUSE ??? VPS with 30GB SSD for € 25 / month

- LinuxCloudVPS – offers a managed openSUSE ??? VPS with 20GB SSD for € 26 / month

After purchasing a VPS, you need to install openSUSE. In my case, I have chosen a partitioning setup where I separate the operating system from the data partitions. Because this server is hosting a website, the data partitions are not located at /home. Rather, I like to make partitions for the WordPress application, the MariaDB database and the Nginx configuration files. My partition setup:

- Total size: 50 GiB

- BIOS Boot partition (8 MiB)

- Swap partition (2 GiB)

- Root partition (21 GiB – BtrFS) mounted at /

- WordPress partition (20 GiB – XFS) mounted at /srv/www

- MariaDB partition (6 GiB – XFS) mounted at /var/lib/mysql

- Nginx partition (1 GiB – XFS) mounted at /etc/nginx

See also the screenshot of the expert partitioner below:

After configuring the partition setup that you like, complete the openSUSE Tumbleweed installation on your VPS server.

Install Nginx and create your first static page

Nginx (pronounced Engine X) is a webserver / loadbalancer that you can use to provide or block access to certain parts of WordPress. For instance blocking direct access to PHP files or hidden files.

Zypper is the package manager that is used for command line installation. There is a very nice cheat sheet (page 1) (page 2) with all commands that are needed to install software via the command line. To install nginx, use the following command:

zypper in nginx

Now we are going to create a basic index.html file that will show us nginx is working. First you need to go to the htdocs folder, by using the following command:

cd /srv/www/htdocs/

If you are interested to see what’s in this folder, use the command ls -l. You will find there is already a file 50x.html in place. We are now going to create this index.html file.

echo "<H1> Your Title </H1>" > index.html

If you want to get fancy: edit the file you just created with the VIM editor.

vi index.html

Use Alt!+I to insert text. Use Esc to exit edit mode. Use :wq! to save.

You can do the same to create an Index.css file. Which you can then also edit using the VIM editor.

echo "h1 {color:blue;}" > index.css

Now its time to start nginx and enable it to start on boot, by using the following commands:

systemctl start nginx systemctl enable nginx

The last thing to do is to open port 80 (HTTP) in firewalld. Use the following commands:

firewall-cmd --permanent --add-port=80/tcp firewall-cmd --reload irewall-cmd --list-all

Now open your favorite browser, go to the IP address that your VPS is hosted on, to see your Index.html file. If you are installing this on a virtualbox server, just type in the localhost IP address:

http://127.0.0.1. http://localhost/

Install MariaDB

For the database that forms the back-end of WordPress, you can choose between using MySQL and MariaDB. MariaDB is a fork of the MySQL database, which was created in response to the Oracle purchase of SUN. One of the driving forces behind this fork is Michael “Monty” Widenius, which is one of the original MySQL founders. The databases have gone their own ways, both have a thriving community. So both MySQL and MariaDB are excellent choices.

In 2014 Red Hat Enterprise Linux has switched to MariaDB by default in RHEL 7. Personally, I think MariaDB is the more ‘open’ project, like LibreOffice is the better version of OpenOffice.org. So I have opted to install MariaDB. This is done by entering the zypper command:

zypper in mariadb mariadb-client mariadb-tools

Now enable the database to startup on boot and start the database service:

systemctl enable mysql systemctl start mysql

If you want to see if everything is running, use these commands. The second command helps you to exit back into the command line.

systemctl status mysql mysql-version

Now lets secure the MariaDB database from unwanted access. Type the following command:

sudo mysql_secure_installation

Now you will get the following questions:

Switch to unix_socket authentication?: Y Change the root password?: Y --> set a new secure password! Remove anonymous users?: Y Disallow root login remotely?: Y Remove test database and access to it?: Y Reload privilege tables now?: Y

Now login to your MariaDB database with the new password:

mysql -u root -p ENTER PASSWORD

When you are logged in as root on your VPS, you don’t have to provide a password. This is because MariaDB uses unix_socket authentication (first question), which gives the root user of your VPS access to the root user of the database. So don’t worry if you can enter the database without providing a password.

Next create a database and a database user. I strongly recommend to not use ‘ admin’ as the username. And while you avoid common names; ‘wpuser’ might also be easy to guess. This is way to easy to hack.

create database UNIQUE_DB_NAME; create user UNIQUEDBUSER@localhost identified by 'UNIQUE_DB_USER@'; grant all privileges on UNIQUE_DB_NAME.* to UNIQUE_DB_USER@localhost identified by 'UNIQUE_DB_USER@'; flush privileges;

To see if your database and user are successfully created, use the commands:

SHOW DATABASES; SELECT User FROM mysql.user;

Now that you created a database user, set a password for that user. I would advice that your newly created user gets a different password as your root database user. This is done by entering the following commands:

USE mysql; ALTER USER 'UNIQUE_DB_USER'@'localhost' IDENTIFIED BY '############'; flush privileges; exit

Install PHP7 and PHP7-FPM

PHP and the FastCGI Process Manager (PHP-FPM) are used by WordPress to communicate between WordPress, Nginx and the MariaDB database. WordPress is written in PHP, a powerful and versatile programming language. The latest version, PHP 7.4 has a greatly improved performance over PHP 5.6. This is the big advantage.

Source: Kinsta – The Definitive PHP 5.6, 7.0, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4 Benchmarks (2020)

Of course there are also many programmatic improvements, but this is less relevant for people who just want to run WordPress. At the beginning of Fossadventures, I used HHVM and Hack instead of PHP and PHP-FPM. But that crashed a lot. So I got rid of this and replaced this with PHP and PHP-FPM.

PHP-FPM is an alternative (better) implementation of FastCGI, which is a better implementation of CGI. Okay that tells you nothing. So lets start with CGI, which stands for Common Gateway Interface. CGI is a protocol for web servers (such as Nginx) to interface with PHP. It enables dynamic content generation and processing (1). FastCGI is what it sounds like, a faster re-implementation of CGI with enhanced capabilities. Now we get to PHP-FPM, which improves upon FastGCI. A couple of examples of improvements (2) are:

- Advanced process management with graceful stop/start;

- Emergency restart in case of accidental opcode cache destruction;

- Accelerated upload support;

- Dynamic/static child spawning;

- And much more.

Sounds impressive. From my experience, it works incredibly well. You can install both PHP7 and PHP7-FPM by entering the following command:

zypper in php7 php7-mysql php7-fpm php7-gd php7-mbstring php7-zlib php-curl php-gettext php-openssl php-zip php7-exif php7-fileinfo php7-imagick

Now let’s edit some configuration files. This is the same instruction as provide by Howtoforge (3), just updated for PHP 7. For your convenience, I will detail every command here below.

We first need to create the PHP-FPM configuration file. This is done by using the commands:

cd /etc/php7/fpm/

ls -l

cp php-fpm.conf.default php-fpm.conf

vi php-fpm.confNow use Alt+I to go into the edit mode. Uncomment (remove the semicolomn) of the following lines and change the log_level:

pid = run/php-fpm.pid error_log = log/php-fpm.log syslog.facility = deamon syslog.indent = php-fpm log_level = warning (change from the default) events.mechanism = epoll systemd_interval = 10

Exit and save by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Now we move to the website configuration file and we create another PHP-FPM configuration file.

cd php-fpm.d ls -l cp www.conf.default YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf ls -l vi YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf

Then we make adjustments by entering Alt+I and making the following changes:

user = nginx group = nginx listen = /var/run/php-fpm.sock listen.owner = nginx (uncomment by removing the ;) listen.group = nginx (uncomment by removing the ;) listen.mode = 0660 (uncomment by removing the ;)

Exit and save by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Next we are going to edit the php.ini file. This is done by typing the following commands:

cd /etc/php7/cli/ ls -l vim php.ini

We make adjustments by entering Alt+I. Go to the section ‘Data Handling’ (line 616) and find the section post_max_size. Make the following adjustment:

post_max_size = 12M

Go to the section ‘Paths and Directories’ (line 733) and then find the section CGI.fix_pathinfo. Make the following adjustment:

cgi.fix_pathinfo=0

Go to the section ‘File Uploads’ (line 832) and then find the section upload_max_filesize. Make the following adjustment:

upload_max_filesize = 6M

Go to the section ‘Module Settings’ (line 947) and then find the section [Pdo_mysql]. Make the following adjustment:

pdo_mysql.cache_size = 2000 (this line is new) pdo_mysql.default_socket=

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Now copy the php.ini file to the conf.d directory:

cp /etc/php7/cli/php.ini /etc/php7/conf.d/php.ini cd /etc/php7/conf.d/ ls -l

Now we want to setup Nginx to work with PHP-FPM. Before we make this change, it is very important that we create a backup of the nginx.conf file. In case we screw anything up, we have a backup that we can restore!

cd /etc/nginx/ ls -l cp nginx.conf nginx.conf.backup01 ls -l

Now we can safely edit the nginx.conf file. We do this by entering the command and pressing Alt+I to go into edit mode:

vi nginx.conf

Create a new line just below “include conf.d/*.conf;” and put in the code:

client_max_body_size 20M;

Make the following adjustments just below “location / {“. Add index.php to the index line and then add the line with try_files:

index index.php index.html index.htm; try_files $uri $uri/ /index.php?$args;

Right below this section at a blank line, add the following code:

location ~ .php$ {

root /srv/www/htdocs;

try_files $uri =404;

include /etc/nginx/fastcgi_params;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME $document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

}

After this, go to the line that says error_page 404… and change the .html into .php.

error_page 404 /404.php; error_page 405 /405.php;

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Let’s make sure that the nginx.conf file still works by entering:

nginx -t

Now we like to change the ownership of the php-fpm.pid and php-fpm.sock files to nginx. We do this by entering the following commands:

cd /var/run/ ls -l chown nginx:nginx php-fpm.pid chown nginx:nginx php-fpm.sock ls -l

If we have no errors, we can savely restart Nginx and start and enable PHP-FPM:

systemctl enable php-fpm systemctl start php-fpm systemctl restart nginx

To test the working of PHP, you can create a test file in the ‘htdocs’ folder, just as we did with the index.html and index.css files.

cd /srv/www/htdocs/ echo "<?php phpinfo(); ?>" > test.php

To test if the file is succesfully created, you can use vim to read the file and then exit.

vi test.php

:q!

It is time to try out if PHP has succesfully installed. To do so, you need to start PHP-FPM and restart Nginx.

nginx -t

systemctl start php-fpm

systemctl restart nginxOpen your favorite browser, go to the IP address that your VPS is hosted on and add “/test.php” (or your website name/test.php) to see the status of your PHP installation. If you are installing this on a virtualbox server, just type in the localhost IP address:

http://127.0.0.1./test.php http://localhost/test.php

You will be greeted by the PHP status page.

For security reasons remove the test.php file. This is done via the following command.

cd /srv/www/htdocs/ ls -l rm test.php ls -l

Create a Nginx Virtualhost file for your website

The first thing to do is to create a Nginx Virtualhost file for your website. This file contains all the specific Nginx information regarding your website, like its name, methods for accessing the website, locations that you want to block etcetera. Create and edit the file using the following commands:

cd /etc/nginx/vhosts.d ls -l echo "server" > YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf ls -l vi YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf

Now lets start editing this file (remember Alt+I) by writing in the following text inside the Nginx configuration file:

server {

# This line for redirect non-www to www

server_name YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.com; rewrite ^(.*) http://www.YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.com$1 permanent;

listen 80;

}

server {

server name www.YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.com;

root /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/;

index index.php index.html index.htm;

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ /index.php$args;

}

error_page 404 /404.php

location = /404.php {

root /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/;

}

error_page 500 502 503 504 /50x.html;

location = /50x.html {

root /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/;

}

location ~ .php$ {

root /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/;

fastcgi_keep_conn on;

#fastcgi_pass 127.0.0.1:9000;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_index index.php;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME

$document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

include /etc/nginx/fastcgi_params;

}

}

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Now we are going to create the root location for your website, that you have just specified in the nginx vhosts file. Remember this line:

root /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/;

That directory doesn’t exist yet! So now we need to create this folder by entering the commands below. We will also copy the index.html, index.css and 50x.html files:

mkdir -p /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/ cd /srv/www/htdocs/ cp index.html /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/index.html cp index.css /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/index.css cp 50x.html /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/50x.html cd /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/ chown nginx:nginx index.html chown nginx:nginx index.css chown nginx:nginx 50x.html ls -l

Because we now have the nginx vhosts file, we don’t need everything in the main nginx configuration anymore. So we will edit the main nginx configuration file again.

Before we start editing, let’s first create a backup. And then open the configuration file with Vim. Use the code below:

cd /etc/nginx/ cp nginx.conf nginx.conf.backup02 ls -l vi nginx.conf

Remove this section:

location ~ .php$ {

root /srv/www/htdocs;

try_files $uri =404;

include /etc/nginx/fastcgi_params;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME $document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

}

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Now test your nginx configuration file.

nginx -t

If there are errors, you should restore the nginx.conf file from the backup you just created. This is done by the command (only use this if you found errors!):

cp YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf.backup02 YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf

If there are no errors, restart nginx:

systemctl restart nginx

Now open your favorite browser, go to the IP address that your VPS is hosted on, to see your Index.html file. If you are installing this on a virtualbox server, just type in the localhost IP address:

http://127.0.0.1. http://localhost/

Register your Domain name and configure your DNS settings

This might also be a good time to add your website name to your DNS. This way, you don’t have to enter the IP address all the time. If you haven’t registered your website name yet, this is the time to do it! Most of the VPS providers can also provide you with a domain name. If not, there are plenty of commercial alternatives. I registered with TransIP.nl. Create the folowing DNS records:

Name: * TTL: 1 hour Type: A IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv4_ADDRESS Name: * TTL: 1 hour Type: AAAA IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv6_ADDRESS Name: @ TTL: 1 hour Type: A IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv4_ADDRESS Name: @ TTL: 1 hour Type: AAAA IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv6_ADDRESS Name: www TTL: 1 hour Type: A IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv4_ADDRESS Name: www TTL: 1 hour Type: AAAA IP address: YOUR_VPS_IPv6_ADDRESS

You probably have to wait 1-5 minutes for the DNS records to be synchronized with the other name servers worldwide. But once that is complete, you can open your favorite browser and visit your site at:

http://www.YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.com

Your index.html file should automatically load.

Install WordPress

After all this work, it is finally time to install WordPress. We first need to go to the directory where we will install WordPress. Then we will remove the index.html and index.css files we created.

cd /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/ ls -l rm index.html rm index.css ls-l

We will now retreive the latest WordPress zip file and unzip it. This will put all files in a subfolder called WordPress. Because we want these files in the YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME folder, we move these files to the current directory. Finally, we remove the empty WordPress folder and the WordPress Zip file.

wget wordpress.org/latest.zip unzip latest.zip mv wordpress/* . # rmdir wordpress/ && rm latest.zip

Now we need to connect our WordPress instance to the MariaDB database that we have created. This is done by creating and editing the wp-config.php file. To make sure Nginx has the right access level, we will change the ownership of all files in your websites directory. Use the following commands:

cp wp-config-sample.php wp-config.php chown nginx:nginx -R /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/ vi wp-config.php

Press Alt + I to go into edit mode and make the following changes:

define('DB_NAME', 'UNIQUE_DB_NAME');

define('DB_USER', 'UNIQUEDBUSER');

define('DB_PASSWORD', 'UNIQUEDBUSER@');

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

We referenced the 404.php file in the Nginx configuration and in the Nginx Vhosts configuration. We make this file available by using the following commands:

cp /srv/www/htdocs/wp-content/themes/twentytwenty/404.php /srv/www/htdocs/404.php cp /srv/www/htdocs/404.php /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/404.php chown nginx:nginx /srv/www/htdocs/404.php chown nginx:nginx /srv/www/YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME/404.php

Now enter the domain of your website in your favorite browser. You will now be redirected to the installation screens. In the first screen, pick the language that is used in the WordPress Dashboard.

In the next screen, you fill in the website name, your admin name and your admin password. Of course you will make this name unique and use a strong password!

The third and final screen tells you that you are ready to go!

By clicking on Log In, you are directed to the WordPress Log-in page. Now you can start configuring the site. Before you start doing that, you want to make some server side improvements first:

- Install phpMyAdmin to administer your database

- Enable GZIP compression

- Harden your Nginx configuration

- Enable HTTPS

Install phpMyAdmin

phpMyAdmin is a great tool to visually check (and edit) what’s in your database. This might be a life saver for some more exotic issues, that cannot be fixed from the WordPress Admin Dashboard. However, I recommend blocking the phpMyAdmin dashboard by default in your Nginx setup. Only when you really need it, unblock it in Nginx. Then make the changes and block it again. Because it is such a powertool, you should limit access to it as much as possible. That said, let’s start with the installation by using the following commands (this package contains Capital Letters):

zypper in phpMyAdmin

Type ‘y’ to accept all dependent packages to be installed. Second we will create a htpasswd file. Use the commands:

htpasswd -c /etc/nginx/htpasswd UNIQUE_PHPMYADMIN_USER ENTER A NEW SECURE PASSWORD

Now we are going to create a new the Nginx configuration file for phpMyAdmin. Use the following commands:

cd /etc/nginx/vhosts.d ls -l echo "server" > phpMyAdmin.conf ls -l vi phpMyAmin.conf

Now press Alt + I to go into edit mode. Now complete the file by typing the following code.

server {

server_name 01.01.001.001;

root /srv/www/htdocs;

index index.php index.html index.htm;

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ /index.php?$args;

}

location ~ ^/phpMyAdmin/.*\.php$ {

root /srv/www/htdocs/;

#deny all;

#access_log off;

#log_not_found off;

auth_basic 'Restricted Access';

auth_basic_user_file /etc/nginx/htpasswd;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_index index.php;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME $document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

include fastcgi_params;

}

error_page 404 404.php;

location = /404.php {

root /srv/www/htdocs;

}

error_page 500 502 503 504 /50x.html;

location = /50x.html {

root /srv/www/htdocs;

}

# PHP-FPM running throught Unix-Socket

location ~ \.php$ {

root /srv/www/htdocs;

fastcgi_keep_conn on;

#fastcgi_pass 127.0.0.1:9000;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_index index.php;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME $document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

include fastcgi_params;

}

}This is the configuration in which you can access phpMyAdmin (after entering your username and password). For now we will save the Nginx configuration file by pressing Esc and type:

:wq!

Test your nginx configuration file. If there are no errors, restart nginx:

nginx -t systemctl restart nginx

Now we need to create a symbolic link from phpMyAdmin to the htdocs directory. This is done by entering the following command:

ln -s /usr/share/phpMyAdmin /srv/www/htdocs/phpMyAdmin chown nginx:nginx -R /usr/share/phpMyAdmin

Now we need to create a symbolic link from phpMyAdmin to the nginx conf.d directory. This is done by entering the following command:

ln -s /etc/phpMyAdmin/config.inc.php /etc/nginx/conf.d/config.inc.php chown nginx:nginx /etc/phpMyAdmin/config.inc.php

The final thing we need to do is give Nginx access to the php session. This is done by using the command:

chown nginx:nginx -R /var/lib/php7

Try out to login to the phpMyAdmin dashboard. Enter your IP followed with /phpMyAdmin:

http://01.01.001.001/phpMyAdmin

You should now see your phpMyAdmin dashboard.

When you are done checking out it is time to go back into your Nginx configuration file and block access completely. Make the following changes (press Alt +I to go into edit mode) to the phpMyAdmin.conf file:

location ~ ^/phpMyAdmin/.*\.php$ {

root /srv/www/htdocs/;

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

#auth_basic 'Restricted Access';

#auth_basic_user_file /etc/nginx/htpasswd;

fastcgi_pass unix:/var/run/php-fpm.sock;

fastcgi_index index.php;

fastcgi_param SCRIPT_FILENAME $document_root$fastcgi_script_name;

include fastcgi_params;

}Save the Nginx configuration file by pressing Esc and type:

:wq!

Test your nginx configuration file. If there are no errors, restart nginx:

nginx -t systemctl restart nginx

Now try accessing your phpMyAdmin page again by entering the same URL:

http://01.01.001.001/phpMyAdmin

If everything works, you should see a Nginx 403 error, telling you that access is denied. Which will prevent bruteforce attacks on your phpMyAdmin dashboard.

Optimize and harden your Nginx configuration

One big speed improvement is one that is easy to implement is enabling Gzip compression. This speeds up the delivery of files to the end user, because if these files are smaller, it takes less time to download them. And every time a webpage is refreshed, a lot of files need to be downloaded. This is done by editing the Nginx configuration file with the Vim text editor. But before we start editing, we will create a backup file so we can always revert to the previous verion. Use the following commands:

cd /etc/nginx/vhosts.d

ls -l

cp YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf.backup01

ls -l

vi YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.confWe go into edit move by pressing Alt + I. Now we need to add some code below “server {” and above “location {“.

gzip on;

gzip_comp_level 5;

gzip_min_length 256;

gzip_proxied any;

gzip_vary on;

gzip_types

text/css

text/plain

text/javascript

test/xml

application/javascript

aplication/json

application/x-javascript

application/xml

application/rss+xml

application/xhtml+xml

application/x-font

application/x-font-ttf

application/x-font-otf

application/x-font-opentype

application/x-font-truetype

application/x-font-woff

application/x-font-woff2

application/vnd.ms-fontobject

font/opentype

font/otf

font/ttf

image/svg+xml

image/x-icon;We also want to set the time that files can stay in the browser cache. A good caching time can differ from site to site. My blogs don’t get updated regularly. I write a blog post every 1 or 2 months. So I have chosen a caching time of 3 weeks. If you post every week, you might want to lower this to 7 days. The browser caching time is specified by adding the following code (directly below the gzip text):

location ~* \.(jpg|jpeg|png|gif|bpm|ico|css|js|pdf)$ {

expires 21d;

}We are not done yet! We also want to block off certain parts of the site that hackers shouldn’t have access to. This is done by adding the following code (directly below the browser caching text):

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ /index.php?$args;

}

location ~* /wp-includes/.*.php$ {

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

}

location ~* /wp-content/.*.php$ {

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

}

location ~* /(?:uploads|files)/.*.php$ {

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

}

location = /xmlrpc.php {

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

}

location = /latest.zip {

deny all;

access_log off;

log_not_found off;

}Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Now test your nginx configuration file.

nginx -t

If there are errors, you should restore the nginx.conf file from the backup you just created. This is done by the command (only use this if you found errors!):

cp YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf.backup01 YOUR_WEBSITE_NAME.conf

If there are no errors, restart nginx:

systemctl restart nginx

Enable HTTPS

Now it is time to change our WordPress website from HTTP to HTTPS. For this, we need an SSL certificate. Which the Let’s Encrypt organsisation provides. Certbot is the official tool to request Let’s Encrypt certificates. So we first need to add the Certbot repository. This is done by using the following commands:

zypper addrepo https://download.opensuse.org/repositories/devel:/languages:/python:/certbot/openSUSE_Tumbleweed/devel:languages:python:certbot.repo

zypper addrepo https://download.opensuse.org/repositories/home:/ecsos:/server/openSUSE_Tumbleweed/home:ecsos:server.repo

zypper ref

Now it will ask you if you will trust the repositories. Type ‘a’ + ‘Enter’ to always trust this repository. After this is done, we can install the Certbot packages. Use the following command:

zypper in certbot-common certbot-doc certbot-systemd-timer python3-certbot python3-certbot-nginx

You will be asked to install certain other packages that are dependencies of the above packages. Type ‘y’ + ‘Enter’ to accept this proposal.

Now we will run the certbot application on the command line by using the command:

certbot --nginx

The Certbot application will ask some questons. Put in the following answers.

- Enter your e-mail address

- Agree to the Terms of Service (select Yes)

- Decide if you want the EFF newsletter (I have selected Yes)

- Leave the input blank to select all options (press Enter)

- Now redirect everything to HTTPS (select 2)

Now that part is finished. We just need to open the firewall for HTTPS traffic. Use the following commands:

firewall-cmd --zone=public --add-service=https --permanent firewall-cmd --zone=public --add-port=443/tcp --permanent firewall-cmd --reload firewall-cmd --list-all

Now enter the address of your website in the browser and check if you can see the lock symbol in your browser. That means you have succesfully installed and configured certbot!

We also want certbot to automatically renew. This can be done by using Crontab to renew every month. Open the crontab file of certbot by using the following commands:

cd /etc/cron.d/ ls -l vi certbot

Press Alt + I to go into edit mode and uncomment (remove the #) of the lines and specify the time interval to renew the certbot certificates. I have specified to run this script every 9 days at 4:10 AM.

renew all certificates methode: renew 10 4 9 * * root /usr/bin/certbot renew

Save and exit by pressing the ESC key and typing the following command:

:wq!

Essential WordPress plugins

The last thing to do to make your WordPress setup complete is to install lots of plugins! A general recommendation is to reduce the numer of WordPress plugins to a minimum. But from my experience, the plugins are the thing that makes WordPress great. You want a performant and secure website. And there are many free and paid plugins that help you achieve that goal.

So far, I have 3 paid plugins (Wordfence, Hide My WP Ghost and Easy Updates Manager). You can also use the free versions, which are still a great option. Below is my list of essential WordPress plugins and the reason why I use them.

Wordfence Security

Wordfence is an endpoint Web Application Firewall and a malware scanner. It greatly enhances the security of your WordPress site by blocking known malicious traffic.

Hide My WP Ghost

Hide My WP Ghost is a security plugin that hides / changes a lot of common WordPress URLs. It also changes the names of plugins and themes to random names. This makes sure that automated attacks against your WordPress site will not work. And that it is harder to gain insight in the vulnerable plugins and themes that you are using.

Easy Updates Manager

Managing all your plugin updates can be a time consuming effort. What if a plugin can do all the work for you? I have set Easy Updates Manager to update all minor WordPress versions and to update all plugins and themes. The premium plugin automatically makes a backup of my site (via UpdraftPlus) before updating. And I get notified via Slack (e-mail is also a possibility).

UpdraftPlus – Backup/Restore

UpdraftPlus is a great Backup/Restore plugin for WordPress. I use it to backup my site every 14 days to my Google Drive. I might consider going Premium in the future, as this also allows Cloning and Migration, which is useful for creating a cloned test site.

HTTP Headers

This plugin allows me to set Security options in my HTTP header.

Contact Form 7

This is a popular WordPress plugin for creating a contact form. It can also send out e-mails when someone submits a request, but don’t want my server to have that ability.

Flamingo

Instead I use Flamingo to store the messages that are submited via the contact form.

WP Mail SMTP by WPForms

This replaced the default PHP mail function and enables me to send outgoing emails via SMTP and Transip as the mailprovider.

Check & Log Email

This allows me to see which e-mails have been send from my WordPress site.

WP Statistics

This plugin enables me to see the number of visits to my website and per page. It is less comprehensive as Google Analytics. But its more than enough for my use case.

Google XML Sitemaps

The Google XML Sitemaps plugin makes sure that my site is indexed by Google. This is not needed if you use more elaborate SEO plugins.

Broken Link Checker

Once you start writing a lot of blogs, your will also link to other sites. At a certain time, these links might brake. This reduces the reading experience of your readers. This is also bad for your SEO. This plugin helps you to find these problems and repair them.

Redirection

This plugin is also related to errors on your website that will start to appear over time. This time related to 301 (redirect) and 404 (page nog found) errors. This plugin helps your to find these problems and repair them.

WP Super Cache

It is a caching plugin. It makes my website load faster.

Autoptimize

It is a plugin that minifies my HTML, CSS and Javascript. It makes my website load faster.

Asset Cleanup: Page Speed Booster

This is a plugin that can load/unload (un)needed Javascript files for certain parts of the site. It makes my website load faster.

Optimole

This plugin helps me to optimizes images (resize and compress) and enables lazy-loading of images. It makes my website load faster.

OMGF

This plugin stores all Google Fonts that are used on my website locally, so when loading my website, people are not redirected to Google. It makes my website load faster.

WP-Optimize

This plugin cleans and optimizes my database. This will result in a very small speed inprovement.

Profilepress

This plugin allows me to use my own picture from my own WordPress media library for when I log in.

Yoast Duplicate Post

This plugin enables me to quickly duplicate an older blog post to use as a template for a new blog post.

Conclusion

I hope that this extensive guide was helpful in getting your new website up-and-running. There is so much more that you should now do:

- Select a nice looking theme

- Customize your theme

- Configure all plugins

- Remove all default posts

- Add the Site and Sitemap to Google Search Console

One important addition. If your start writing blog posts and create pages with your admin user, you make it very easy for hackers to brute force hack your website. Therefore I would recommend a separation of roles. Create a second user for yourself with only editing rights. And use that user account to create pages and write blog posts.

I leave the rest for you to work out. Best of luck!

Publishing date: 25-03-2020

Updated: 29-07-2021

Reducing memory consumption in librsvg, part 3: slack space in Bézier paths

We got a bug with a gigantic SVG of a map extracted from

OpenStreetMap, and it has about 600,000 elements. Most of them are

<path>, that is, specifications for Bézier paths.

A <path> can look like this:

<path d="m 2239.05,1890.28 5.3,-1.81"/>

The d attribute contains a list of commands to

create a Bézier path, very similar to PostScript's operators. Librsvg

has the following to represent those commands:

pub enum PathCommand {

MoveTo(f64, f64),

LineTo(f64, f64),

CurveTo(CubicBezierCurve),

Arc(EllipticalArc),

ClosePath,

}

Those commands get stored in an array, a Vec inside a PathBuilder:

pub struct PathBuilder {

path_commands: Vec<PathCommand>,

}

Librsvg translates each of the commands inside a <path d="..."/>

into a PathCommand and pushes it into the Vec in the

PathBuilder. When it is done parsing the attribute, the

PathBuilder remains as the final version of the path.

To let a Vec grow efficiently as items are pushed into

it, Rust makes the Vec grow by powers of 2. When we add an item, if

the capacity of the Vec is full, its buffer gets realloc()ed to

twice its capacity. That way there are only O(log₂n) calls to

realloc(), where n is the total number of items in the array.

However, this means that once we are done adding items to the Vec,

there may still be some free space in it: the capacity exceeds the

length of the array. The invariant is that

vec.capacity() >= vec.len().

First I wanted to shrink the PathBuilders so that they have no extra

capacity in the end.

First step: convert to Box<[T]>

A "boxed slice" is a contiguous array in the heap, that cannot grow or shrink. That is, it has no extra capacity, only a length.

Vec has a method into_boxed_slice which does

eactly that: it consumes the vector and converts it into a boxed

slice without extra capacity. In its innards, it does a realloc()

on the Vec's buffer to match its length.

Let's see the numbers that Massif reports:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n time(i) total(B) useful-heap(B) extra-heap(B) stacks(B)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

23 22,751,613,855 1,560,916,408 1,493,746,540 67,169,868 0

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

before

30 22,796,106,012 1,553,581,072 1,329,943,324 223,637,748 0

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

after

That is, we went from using 1,493,746,540 bytes on the heap to using 1,329,943,324 bytes. Simply removing extra capacity from the path commands saves about 159 MB for this particular file.

Second step: make the allocator do less work

However, the extra-heap column in that table has a number I don't

like: there are 223,637,748 bytes in malloc() metadata and unused

space in the heap.

I suppose that so many calls to realloc() make the heap a bit

fragmented.

It would be good to be able to read most of the <path d="..."/> to

temporary buffers that don't need so many calls to realloc(), and

that in the end get copied to exact-sized buffers, without extra

capacity.

We can do just that with the smallvec crate. A SmallVec has the

same API as Vec, but it can store small arrays directly in the

stack, without an extra heap allocation. Once the capacity is full,

the stack buffer "spills" into a heap buffer automatically.

Most of the d attributes in the huge file in the bug have

fewer than 32 commands. That is, if we use the following:

pub struct PathBuilder {

path_commands: SmallVec<[PathCommand; 32]>,

}

We are saying that there can be up to 32 items in the SmallVec

without causing a heap allocation; once that is exceeded, it will work

like a normal Vec.

At the end we still do into_boxed_slice to turn it into an

independent heap allocation with an exact size.

This reduces the extra-heap quite a bit:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

n time(i) total(B) useful-heap(B) extra-heap(B) stacks(B)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

33 24,139,598,653 1,416,831,176 1,329,943,212 86,887,964 0

^^^^^^^^^^

Also, the total bytes shrink from 1,553,581,072 to

1,416,831,176 — we have a smaller heap because there is not so much

work for the allocator, and there are a lot fewer temporary blocks

when parsing the d attributes.

Making the code prettier

I put in the following:

/// This one is mutable

pub struct PathBuilder {

path_commands: SmallVec<[PathCommand; 32]>,

}

/// This one is immutable

pub struct Path {

path_commands: Box<[PathCommand]>,

}

impl PathBuilder {

/// Consumes the PathBuilder and converts it into an immutable Path

pub fn into_path(self) -> Path {

Path {

path_commands: self.path_commands.into_boxed_slice(),

}

}

}

With that, PathBuilder is just a temporary struct that turns into an

immutable Path once we are done feeding it. Path contains a boxed

slice of the exact size, without any extra capacity.

Next steps

All the coordinates in librsvg are stored as f64, double-precision

floating point numbers. The SVG/CSS spec says that single-precision

floats are enough, and that 64-bit floats should be used only for

geometric transformations.

I'm a bit scared to make that change; I'll have to look closely at the

results of the test suite to see if rendered files change very much.

I suppose even big maps require only as much precision as f32 —

after all, that is what OpenStreetMap uses.

Member

Member DimStar

DimStar