Digest of YaST Development Sprint 116

2021 is here and it doesn’t look like it’s going to be a boring year… at least in the YaST side! The YaST team just restarted the work a couple of weeks ago and we already have some development news to share with you, including some improvements our users requested through the openSUSE’s End of the Year Community Survey.

- Writing NetworkManager configuration during system installation

- Refining the mechanism to reuse existing EFI partitions

- Using more stable and consistent names to reference devices in the bootloader

- Improving AutoYaST behavior when no product has been specified

- Updating the roles offered by yast2-vm

- Many more small improvements here and there

Let’s start with an installer improvement quite some people was waiting for. Both openSUSE and SUSE

Linux Enterprise can use either wicked or NetworkManager to handle the system’s network

configuration. Only the former can be fully configured with YaST (which is generally not a problem

because there are plenty of tools to configure NetworkManager). Moreover, during the standard

installation process, wicked is always used to setup the network of the installer itself. If the

user decides to rely on wicked also in the final system, then the configuration of the installer

is carried over to it. But, so far, if the user opted to use NetworkManager then the installer

configuration was lost and the network of the final system had to be be configured again using

NetworkManager this time. Not anymore!

That’s not the only installer behavior we have refined based on feedback from our users. In some scenarios, the logic used to decide whether an existing EFI System Partition (ESP) could be reused was getting in the way of those aiming for a fine-grained control of their partitions. That should now be fixed by the changes described in this pull request, that have been already submitted to Tumbleweed and will be part of the upcoming releases (15.3) of both openSUSE Leap and SLE.

We also fine-tuned how hibernation is configured during installation. To be precise, we improved the

corresponding resume= parameter passed to the kernel by the bootloader. From now on, that

parameter will use a device name that will be fully

consistent with the names used in other parts of

the installer and that will be often based on the swap

UUID.

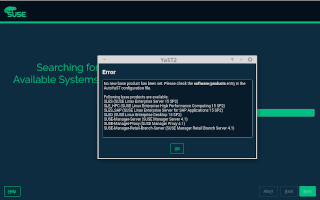

As usual, AutoYaST also got its quota of love during this sprint. This time on form of an usability improvement. As you may know, SUSE Linux Enterprise offers a whole set of products for different needs. When using AutoYaST to upgrade a system using a multiproduct repository, it’s necessary to specify the concrete product in the AutoYaST profile. When that was not correctly done, the system failed in a not-exactly-elegant way. In upcoming versions of products of the SLE family, that will be handled in a much nicer way.

And apart from the installation and auto-installation process, we also introduced several small fixes and improvements in other parts of YaST. Like bringing up-to-date the options offered by yast2-vm, speeding up the process of reading the network devices in s390 mainframes, improving the usability when the hostname needs to be adapted… and many other things you can check in Github or the Open Build Service if you want to know more.

As you can see, the new year has not diluted our enthusiasm to keep improving YaST bit by bit. So now it’s time to go back to work, hoping to meet you again in a couple of weeks with more news. Have a lot of fun!

Session One Meetup Generates Enhancements, Actions

The first session of the openSUSE Project’s meetup regarding the End of the Year Survey Results on Jan. 23 is already starting produce some actionable items from contributors.

The session on openSUSE’s Jitsi instance had engagement from about 20 people from around the globe.

Topics discussed in the two-hour session focused on addressing pain points, transferring knowledge and promoting openSUSE projects.

Members of the “let’s improve the openSUSE learning experience” shared statics and analysis from the survey and attendees engaged in generating ideas and actions to enhance and improve the above mentioned items.

Actions to take voiced during the session were enhancing the project’s websites to better direct visitors to appropriate communication mediums, documenting easier “getting started” guides and coming up with monthly or quarterly workshops.

The discussions during the meetup lead to other topics like having more surveys to extract greater information about hardware difficulties and other pain points. Discussions also talked about enhancing the wording and live images on software.opensuse.org.

Most of the ideas were captured on https://etherpad.opensuse.org/p/EOY2020Meetup.

The next sessions will start at 13:00 UTC on openSUSE’s Jitsi instance on Jan. 30.

Topics to be discussed in the Jan. 30 session include:

- Tools driving switchers to openSUSE (Where are users coming from)

- Discuss flagship project/s

- Expanding global users

- Increasing diversity

- Increase usage with people under 34

The meetup will take place at https://meet.opensuse.org/EOY2020.

More details about the End of the Year Community Survey results can be found on the openSUSE Wiki.

VICE v3.5 | Versatile Commodore Emulator on openSUSE

openSUSE Tumbleweed – Review of the week 2021/03

Dear Tumbleweed users and hackers,

Shame on me for giving you the information about the changes in Tumbleweed during this week only now, but at least technically this is still the review of Week 03. Since the last weekly review, there have been 6 snapshots published (0114, 0115, 0118, 0119, 0120, and 0121).

The main changes this week include:

- Linux kernel 5.10.7

- GNOME 3.38.3

- Mozilla Tunderbird 78.6.1

- Mesa 20.3.3

- openSSH 8.4p1

- Tcl/Tk 8.6.11

- Bash 5.1.4

- PHP 8 was added

- Wine 6.0

- Multiple versions of python 3 parallel installable. Besides all python-FOO packages being built for python 3.8, they are now also built for python 3.6 (where they make sense and are buildable). The packages are named python36-FOO and python38-FOO. As Python 3.8 is currently the default python 3 interpreter in Tumbleweed, all python38-FOO packages provide/obsolete the python3-FOO symbol, in order to facilitate the migration to the new naming scheme.

The future changes that are currently being planned, worked on and being tested include:

- Postfix: change the default database format to lmdb, migrating away from BerkleyDB.

- icu 68.1: breaks a few things like PostgreSQL. Staging:I

- Rust 1.49: breaks librsvg

- Automake 1.16.3

- Autoconf 2.70: breaks quite a few packages. The list of failures has been noted on the current SR; no active staging left for it (no progress in the last days/weeks on it)

- Migrate to LUA 5.4 as main lua interpreter, mainly relevant in context of RPM and thus the distro bootstrap

Latency Numbers Every Team Should Know

We design systems around the size of delays that are expected. You may have seen the popular table “latency numbers every programmer should know” which lists some delays that are significant in technology systems we build.

Teams are systems too. Delays in operations that teams need to perform regularly are significant to their effectiveness. We should know what they are.

Ssh to a server on the other side of the world and you will feel frustration; delay in the feedback loop from keypress to that character displayed on the screen.

Here’s some important feedback loops for a team, with feasible delays. I’d consider these delays tolerable by a team doing their best work (in contexts I’ve worked in). Some teams can do better, lots do worse.

| Operation | Delay |

| Run unit tests for the code you’re working on | < 100 Milliseconds |

| Run all unit tests in the codebase | < 20 Seconds |

| Run integration tests | < 2 Minutes |

| From pushing a commit to live in production | < 5 Minutes |

| Breakage to Paging Oncall | per SLO/Error Budget |

| Team Feedback | < 2 Hours |

| Customer Feedback | < 1 Week |

| Commercial Bet Feedback | < 1 Quarter |

What are the equivalent feedback mechanisms for your team? How long do they take? How do they influence your work?

Feedback Delays Matter

They represent how quickly we can learn. Keeping the delays as low as the table above means we can get feedback as fast as we have made any meaningful progress. Our tools/system do not hold us back.

Feedback can be synchronous if you keep them this fast. You can wait for feedback and immediately use it to inform your next steps. This helps avoid the costs of context switching.

With fast feedback loops we run tests, and fix broken behaviour. We integrate our changes and update our design to incoporate a colleague’s refactoring.

Fast is deploying to production and immediately addressing the performance degradation we observe. It’s rolling out a feature to 1% of users and immediately addressing errors some of them see.

With slow feedback loops we run tests and respond to some emails while they run, investigate another bug, come back and view the test results later. At this point we struggle to build a mental model to understand the errors. Eventually we’ll fix them and then spend the rest of the afternoon trying to resolve conflicts with a branch containing a week’s changes that a teammate just merged.

With slow deploys you might have to schedule a change to production. Risking being surprised by errors reported later that week, when it has finally gone live, asynchronously. Meanwhile users have been experiencing problems for hours.

Losing Twice

As feedback delays increase, we lose twice:

a) We waste more time waiting for these operations (or worse—incur context switching costs as we fill the time waiting)

b) We are incentivised to seek feedback less often, since it is costly to do so. Thereby wasting more time & effort going in the wrong direction.

I picture this as a meandering path towards the most value. Value often isn’t where we thought it was at the start. Nor is the route to it often what we envisioned at the start.

We waste time waiting for feedback. We waste time by following our circuitous route. Feedback opportunities can bring us closer to the ideal line.

When feedback is slow it’s like setting piles of money on fire. Investment in reducing feedback delays often pays off surprisingly quickly—even if it means pausing forward progress while you attend to it.

This pattern of going in slightly the wrong direction then correcting repeats at various granularities of change. From TDD, to doing (not having) continuous integration. From continuous deployment to testing in production. From customers in the team, to team visibility of financial results.

Variable delays are even worse

In recent times you may have experienced the challenge of having conversations over video links with significant delays. This is even harder when the delay is variable. It’s hard to avoid talking over each other.

Similarly, it’s pretty bad if we know it’s going to take all day to deploy a change to production. But it’s so worse if we think we can do it in 10 minutes, when it actually ends up taking all day. Flaky deployment checks, environment problems, change conflicts create unpredictable delays.

It’s hard to get anything done when we don’t know what to expect. Like trying to hold a video conversation with someone on a train that’s passing through the occasional tunnel.

Measure what Matters

The time it takes for key types of feedback can be a useful lead indicator on the impact a team can have over the longer term. If delays in your team are important to you why not measure them and see if they’re getting better or worse over time? This doesn’t have to be heavyweight.

How about adding a timer to your deploy process and graphing the time it takes from start to production over time? If you don’t have enough datapoints to plot deploy delay over time that probably tells you something ;)

Or what about a physical/virtual wall for waste. Add to a tally or add a card every time you have wasted 5 mins waiting. Make it visible. How big did the tally get each week?

What do the measurements tell you? If you stopped all feature work for a week and instead halved your lead time to production, how soon would it pay off?

Would you hit your quarterly goals more easily if you stopped sprinting and first removed the concrete blocks strapped to your feet?

What’s your experience?

Every team has a different context. Different sorts of feedback loops will be more or less important to different teams. What’s important enough for your team to measure? What’s more important than I’ve listed here?

What is difficult to keep fast? What gets in the way? What is so slow in your process that synchronous feedback seems like an unattainable dream?

The post Latency Numbers Every Team Should Know appeared first on Benji's Blog.

GNOME, VLC, Zypper update in Tumbleweed

Five openSUSE Tumbleweed snapshots were released this week.

The snapshots updated the GNOME desktop, GStreamer, VLC and a couple text editors.

An update of bash 5.1.4 arrived in the latest snapshot 20210120. A few patches were added to the bash version, which is the latest release candidate. The 2.83 version of dnsmasq took care of five Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures; one of the fixes handles multiple identical near simultaneous DNS queries better and another CVE replaced the slightly lesser SHA-1 hash with the SHA-256 hash function, which verifies the DNS answers received are for the questions originally asked. GStreamer 1.18.3 fixed a memory leak and added support for the Apple M1, which made news yesterday as being able to run Linux. Several other GStreamer plugins were updated. Video player VLC updated for version 3.0.12 and added new Reliable Internet Stream Transport access output module compliant with a simple profile. About a dozen more packages were updated in the snapshot including ncurses , openldap2 2.4.57, and perl-Mojolicious 8.71.

The 20210119 snapshot fixed some rendering regressions and some crash in the 20.3.3 version of Mesa. ImageMagick 7.0.10.58 fixed an issue of properly identifying SVG images. An update to the AY configuration file in autoyast2 4.3.65 was made for checking that a valid base product was selected. A few new features were made available in openssh 8.4p1, which prompts a PIN verification to complete a signature operation. The update of text editor nano 5.5 has an option to suppress the title bar and show a bar with basic information; it also removed support for Slang. GNOME’s Wayland display server and X11 window manager mutter 3.38.3 updated translations, set xrandr as the primary output and fixed some crashes. Flatpak 1.10.0 has major new features in this series compared to the 1.8 version, which supports a new repo format that should make updates faster and download less data. PDF renderer poppler also had a new major version with 21.01.0. Poppler has faster jpeg decoding and fixed some potential data loss when fetching a non-existing reference after modifying a document. GNU Privacy Guard updated to 2.2.27 and fixed descriptions of two new options in gpg.conf. There was an improvement to the login screen with gnome-shell 3.38.3 and the update of audio compressor wavpack to 5.4.0 allowed for the assembly of some language optimizations for x86, x64, and arm.

Mozilla Thunderbird 78.6.1 fixed one CVE in snapshot 20210118. CVE-2020-16044, which affected the use-after-free write when handling a malicious COOKIE-ECHO SCTP chunk; this had implication for the email client as well as the Firefox browser. openSUSE’s command line package manager zypper 1.14.42 fixed the extend apt packagemap and the source-download for command help. Another command line package, sudo updated to 1.9.5p1. This version fixed a regression introduced in sudo 1.9.5 where the editor run by sudoedit was set-user-ID root (unless SELinux RBAC was in use); the editor is now run with the user’s real and effective user-IDs. An update of redis to version 6.0.10 fixed a crash in redis-cli after executing a cluster backup. The 2.24 alpine, which is a text-based mail and news client, provided implementation of XOAUTH2 for Yahoo! Mail.

The 20210115 snapshot provided updates for GNOME 3.38.3 with packages gnome-desktop, gnome-maps, gnome-terminal and the evolution information manager all updating a minor version. A minor update was made to the compiler/toolchain llvm11 to version 11.0.1, which provided some random fixes. The snapshot also featured an update to salt 3002.2, which removed the use of an undefined variable in utils/slack.py and restored the ability to specify the amount of extents for a Logical Volume as a percentage. Other packages to update in the snapshot were AppStream 0.13.1, git 2.30.0 brltty 6.2, vala 0.50.3 and vim.

The Linux Kernel was updated to 5.10.7 in snapshot 20210114. Xfce’s thunar file manager updated to version 4.16.2; the package fixed a regression with opening an application and a changes were made to always create new files and folders in a current directory.

dnsmasq icon - Author Justin Clift Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

CUPS-PDF | Print to PDF from any Application

How to install the Yaru (Ubuntu) theme on openSUSE?

Ubuntu 20.10 has a polished GNOME theme. It's called Yaru and it comes in light/dark versions for gtk2 & gtk3. It bundles an icon & cursor theme which is based on the Suru icon theme.

To install the Yaru theme properly on openSUSE, we need to compile a few files first and to do so we require a few tools.

sudo zypper in git meson ninja glib2-devel sasscOnce we have the tools installed, we clone the Yaru theme project from GitHub.

git clone https://github.com/ubuntu/yaru.gitNext, we build the theme & install it.

cd yaru

meson "build" --prefix=/usr

sudo ninja -C "build" installThe Yaru theme will then be available for selection from the GNOME Tweaks configuration tool.

Select Yaru as the Applications, Cursor and Icon themes. You may also select it as the sound theme as well if you want.

Lastly, enable the Dash to Dock extension for GNOME and you should have a polished desktop.

Quick and dirty ipmitool tutorial

Because I always forget

To reboot a SUPERMICRO server:

Just remember that the default user/password might still be ADMIN/ADMIN :)

ipmitool -I lanplus -H $HOST -U USER -P PASSWORD power cycle

To connect to the serial console

ipmitool -I lanplus -H $HOST -U USER -P PASSWORD sol activate

OAK compatibility with all openSUSE

While focused on the openSUSE Innovator initiative as an openSUSE member and official Intel oneAPI innovator, I tested the OAK AI Kit device on openSUSE Leap 15.1, 15.2 and Tumbleweed. With all the work, we made available in the SDB an article on how to install this device on the openSUSE platform. More information can be found at https://en.opensuse.org/SDB:Install_OAK_AI_Kit.

The OpenCV AI Kit, that is, OAK, is a tiny, low-end hardware computing module based on the integrated Intel Movidius Myriad-X AI chip. In comparison to other GPU, CPU, FPGA or TPU-based AI acceleration solutions, Movidius is a VPU architecture with 4.0 TOPS computing capacity. And it is 80 times faster for CV and AI tasks than the well-known OpenMV project, which has only 0.05 TOPS based on the ARM Cortex M7 microcontroller.

The OAK has the same AI chip as the Intel Neural Compute Stick 2 (NCS2) but has more powerful hardware features. OAK shipped with one 1/2.3″ Sony 12MP IMX378 capable of 4K@30fps H.265 video streaming, video AI pipelined processing, and two optional 1MP monochrome global shutters OV9282 cameras for depth sensing, with all 3 cameras it turns the OAK into an RGB+D camera.

For more information, visit https://opencv.org/introducing-oak-spatial-ai-powered-by-opencv/.

Member

Member Futureboy

Futureboy