zypper-upgraderepo-plugin is here

zypper-upgraderepo-plugin adds to zypper the ability to check the repository URLs either for the current version or the next release, and upgrade them all at once in order to upgrade the whole system from command line.

This tool started as a personal project when a day I was in the need to upgrade my distro quicker than using a traditional ISO image, Zypper was the right tool but I got a little stuck when I had to handle repositories: some of them were not yet upgraded, others changed slightly in the URL path.

Who knows how to Bash the problem is not exactly a nightmare, and so I did until I needed to make a step further.

The result is zypper-upgraderepo Ruby gem which can be integrated as a zypper plugin just installing the zypper-upgraderepo-plugin package.

Installing zypper-upgraderepo-plugin

Installing zypper-upgraderepo-plugin is as easy as:

- Adding my repo:

sudo zypper ar https://download.opensuse.org/repositories/home:/FabioMux/openSUSE_Leap_42.3/home:FabioMux.repo - Install the package:

sudo zypper in zypper-upgraderepo-plugin

How to use it

Sometime we want to know the status of current repositories, the command zypper ref does a similar job but it is primarily intended to update the repository’s data and that slow down a bit the whole process.

Instead we can type:

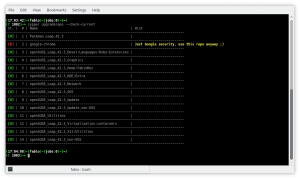

$ zypper upgraderepo --check-current

To know whether or not all the available repositories are upgrade-ready:

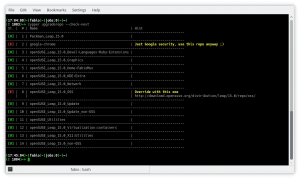

$ zypper upgraderepo --check-next

As you can see from the example above all the enabled repositories are ready to upgrade except for the OSS repo which has a slightly different URL.

# The URL used in the openSUSE Leap 42.3

http://download.opensuse.org/distribution/leap/42.3/repo/oss/suse/

# The suggested one for openSUSE Leap 15.0

http://download.opensuse.org/distribution/leap/15.0/repo/oss/

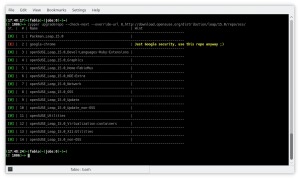

Let’s try again overriding the URL without make any real change:

$ zypper upgraderepo --check-next \

--override-url 8,http://download.opensuse.org/distribution/leap/15.0/repo/oss/

Once everything is ok, and after performed a backup including all the repositories, it’s time to upgrade all the repository at once:

$ sudo zypper upgraderepo --upgrade \

--override-url 8,http://download.opensuse.org/distribution/leap/15.0/repo/oss/

Conclusions

That’s all with the basic commands, more information is available in the wiki page of zypper-upgraderepo gem where all the commands are intended with the only use of the gem, but installing the plugin they are also available as zypper subcommands like shown above, also a man page is available as

$ zypper help upgraderepo

Privacy-friendly Wizard House Quiz

You also do not want to read the lengthy privacy policy https://www.pottermore.com/about/privacy and create an account, just to know your Wizard House Quiz? Here you have a privacy-friendly alternative.

Find your Wizard House

Click the button at your favourite time to learn your Wizard house!

Wizard House names may be protected under some legal acts in some countries.

No personal data from this quiz is stored or transferred.

Automated Decision Making

The following formular is employed to determine your house:

this.house = this.houses[Math.floor(Math.random()*this.houses.length)]

Source Code

<div id="app">

<form style="border: 1px solid black; padding: 5px">

<div class="form-group row">

<label for="staticEmail" class="col-sm-5 col-form-label">Favourite Time:</label>

<div class="col-sm-7">

<button v-on:click="setHouse($event)" class="btn btn-primary btn-sm" id="staticEmail">Now!</button>

</div>

</div>

<div class="form-group row">

<label for="inputPassword" class="col-sm-5 col-form-label">Your Wizard House:</label>

<div class="col-sm-7" id="inputPassword">

{{ house }}

</div>

</div>

</form>

</div>

<script>

var app5 = new Vue({

el: '#app',

data: {

house: '',

houses: [

`Slytherin`,

`Hufflepuff`,

`Ravenclaw`,

`Griffondor`,

]

},

methods: {

setHouse: function (event) {

this.house = this.houses[Math.floor(Math.random()*this.houses.length)];

event.preventDefault();

}

}

})

</script>

Logging from Rust in librsvg

Over in this issue we are discussing how to add debug logging for librsvg.

A popular way to add logging to Rust code is to use the log crate. This lets you sprinkle simple messages in your code:

error!("something bad happened: {}", foo);

debug!("a debug message");

However, the log create is just a facade, and by default the messages do not get emitted anywhere. The calling code has to set up a logger. Crates like env_logger let one set up a logger, during program initialization, that gets configured through an environment variable.

And this is a problem for librsvg: we are not the program's

initialization! Librsvg is a library; it doesn't have a main()

function. And since most of the calling code is not Rust, we can't

assume that they can call code that can initialize the logging

framework.

Why not use glib's logging stuff?

Currently this is a bit clunky to use from Rust, since glib's structured logging functions are not bound yet in glib-rs. Maybe it would be good to bind them and get this over with.

What user experience do we want?

In the past, what has worked well for me to do logging from libraries is to allow the user to set an environment variable to control the logging, or to drop a log configuration file in their $HOME. The former works well when the user is in control of running the program that will print the logs; the latter is useful when the user is not directly in control, like for gnome-shell, which gets launched through a lot of magic during session startup.

For librsvg, it's probably enough to just use an environment

variable. Set RSVG_LOG=parse_errors, run your program, and get

useful output. Push button, receive bacon.

Other options in Rust?

There is a slog crate which looks promising. Instead of using context-less macros which depend on a single global logger, it provides logging macros to which you pass a logger object.

For librsvg, this means that the basic RsvgHandle could create its

own logger, based on an environment variable or whatever, and pass it

around to all its child functions for when they need to log something.

Slog supports structured logging, and seems to have some fancy output modes. We'll see.

Pretty big side-effect

Dolphin and openQA and other assorted bits

Part of this post is about openQA, openSUSE’s automated tool which tests a number of different scenarios, from installation to the behavior of the different desktop environments, plus testing the freshest code from KDE git. Recently, thanks to KDE team member Fabian Vogt, there has been important progress when testing KDE software.

Testing the Dolphin file manager

Those who use KDE software, either in Plasma or in other desktop environments have at least heard of Dolphin, the powerful file manager part of KDE Applications (by the way, have you checked out the recent beta yet?). A couple of weeks ago, in the #opensuse-kde channel, Fabian mentioned the possibility of writing new openQA tests: although there are many tests already, the desktop ones are all but comprehensive given the many possible scenarios. After some discussion back and forth, the consensus was to test Dolphin as it’s a very commonly used in many everyday tasks.

The second part was thinking up what to test. Again, the idea was to focus on common tasks: navigating and creating folders, creating and removing files, and adding elements to Places (the quick-access bar on the left). The first idea also contemplated testing drag-and-drop, but unfortunately such actions aren’t yet supported by openQA, so they were put in the backlog. With these goals in mind, Fabian created a series of tests. This is what being tested:

- Launching dolphin and creating a folder

- Navigating in the folder and creating a text file via context menu (“Create New…”)

- Test navigation via the breadcrumb

- Adding the newly-added folder via Places and ensuring it shows up in other applications

- Remove the folder and the added place

You can see the latest results of the tests for Krypton on openQA. Of course, this does not apply to only the latest unstable code: it is also working for the main distributions.

What does this mean, in practice? openQA is flexible enough to allow even complex tests with multiple operations in succession, and these tests are very useful in catching bugs early, as it has already happened in the past. That doesn’t mean you should be complacent: keep filing those bugs, either to the distro for packaging issues, or to KDE for issues related to the software.

New Krypton links

A small but welcome addition to the Krypton live images is that now the latest build is automatically symlinked to a fixed name (openSUSE_Krypton.$arch.iso, where $arch is either i686 or x86_64. This allows now to link the images directly whenever required: before this change any direct link would break due to the ISO changing name at every rebuild. Doing the same for Argon is on the horizon, but requires some more work before it will happen.

KDE Applications 18.08 beta enters KDE:Applications

As manual testing is still important, the openSUSE KDE:Applications repository now contains the KDE Applications 18.08 beta. If you’re willing to help test the beta, please download the package and file bugs for issues you encounter. In case you’re just using the repository as an add-on, you might want to hold off updating until the final release is out.

Speaking of final release… there might some slight delays in getting it to the distribution this time: part of the KDE team (Antonio, Fabian) is attending Akademy, while others (yours truly) will be away enjoying their hard-earned (?) vacation. In this case, please exercise patience and keep your pitchforks away. ;)

Lunar Eclipse Blood Moon

Tonight, I spent some time on the balkony with my SLR, a glass of Shiraz and the most significant lunar eclipse of the century.

The first steps to a more modern infrastructure

Introduction¶

This is a small write-up of our ongoing effort to move our infrastructure to modern technologies like Kubernetes. It all started a bit before the Hack Week 17 with the microservices and serverless for the openSUSE.org infrastructure project. As it mentions, the trigger behind it is that our infrastructure is getting bigger and more complicated, so the need to migrate to a better solution is also increasing. Docker containers and Kubernetes (for container orchestration) seemed like the proper ones, so after reading tutorials and docs, it was time to get our hands dirty!

Installing and experimenting with Kubernetes / CaaSP¶

We started by installing the SUSE CaaSP product on the internal Heroes VLAN. It provides an additional admin node which sets up the Kubernetes cluster. The cluster is not that big for now. It consists of the admin node, three kube-master nodes behind a load balancer and four kube-minions (workers). The product was in version 2 when we started, but version 3 became available which is the one we're using right now. It worked flawlessly, and we were even able to install the Kubernetes dashboard on top of it, which was our first Kubernetes-hosted webapp.

Since the containers inside Kubernetes are on their own internal network, we needed also a loadbalancer to expose the services to our VPN. Thus, we experimented with Ingress for load balancing of the applications deployed inside Kubernetes, also successfully. A lot of experiments around deployments, scaling and permissions took place afterwards, to get us more familiarized with the new concepts, which of course ended up in us destroying our cluster multiple times. We were surprised to see though the self-healing mechanisms taking over.

Although the experiments took place only with static pages so far, it still allowed us to learn a lot about Docker itself, eg how to create our own images and deploy them to our cluster. It's worth also mentioning the amazing kctl tool, just take a look at its README to realize how much more useful it is compared to the official kubectl.

Time to move to the next layer.

Installing and experimenting with Cloud Foundry / CAP¶

The next step was to install yet another SUSE product, this time the Cloud Application Platform, which offers a Platform as a Service solution based on the software named Cloud Foundry. The first blocker was met here though. CAP requires a working Kubernetes storageclass, which means that we needed to have a persistent storage backend. A good solution would be to use a distributed filesystem solution like Ceph, but due to the time limitations of Hack Week, we decided to go with a simpler solution for now, and the simplest was an NFS server. The CAP installation was smooth from that point, and we managed to login to our Cloud Foundry installation via the command line tool, as well as via the Stratos webUI. A wildcard domain *.cf.mydomain.tld was also needed here.

The idea was quite straightforward here: go to your git repository, and type a simple command like: cf push -m 256M -k 512M myapp. This would deploy a new app directly to Cloud Foundry, giving it 256MB of RAM and 512MB of disk space. As a bonus, it created a domain myapp.cf.domain.tld immediately! So the benefits here were quite obvious, no need to build our own container image with the app and set up a mechanism to deploy it, and no need for the manual step of setting up a DNS. The Ingress LB for Kubernetes that was mentioned before is also obsolete now, as Cloud Foundry handles this as well. The command cf scale could also give us the ability to scale up/down (increase/decrease memory/disk) or scale in/out (increase/decrease number of instances) as well.

Time for stress testing¶

Hack Week 17 was over, so the next days we deployed a few static apps (and one dynamic that needed also a memcached backend), by giving them the absolute minimal disk/RAM (around 10MB ram and 10MB to 256MB disk, depending on the webapp). We triggered a number of bots that started requesting the webpages in a loop, and the results were really impressive: even with such minimal resources and only one instance running, we saw only an increase on the CPU usage to max 15%!

As a second step, we put some static webapps of low importance running in the cluster and we let them public. We're not going to reveal which ones yet though, feel free to guess :) We plan to monitor the resource usage and activity for a few days, and if everything is fine to even put some more important webapps in.

Future tasks¶

There are a lot of future tasks that need to be resolved before we fully hit production. First of all, as mentioned, the NFS storageclass needs to be replaced with a proper distributed filesystem solution. SUSE Enterprise Storage product is a good candidate for it. Furthermore, we'd need to integrate our LDAP server with both CaaSP and CAP accounts. Last but not least, we are very close on making dynamic webpages with relational database needs working.

The overall progress is tracked in a trello board, and of course the internal heroes documentation has more info about the setup. Volunteers are always welcome, feel free to contact us in case you'd like to jump onboard.

Thanks to anybody who helped on setting up the cluster, the SUSE CaaSP and CAP teams for replying to our tons of questions. Special thanks go to Dimitris Karakasilis and Panagiotis Georgiadis for joining me before, during and after Hack Week 17 and still being around, making this from a simple idea to a production-ready project.

On behalf of the openSUSE Heroes team,

Theo Chatzimichos

I'm going to Akademy, again

A little bit less than a month and I will be at Akademy again, KDE's annual conference. This is the place where you can meet one of the most amazing open source communities. To me it's kind of my home community. This is where I have learned a lot about open source, where I contributed tons of code and other work, where I met a lot of awesome friends. I have been to most Akademy events, including the first KDE conference "Kastle" in 2003. But I missed the one last year. I'm more than happy to be back this year in Vienna on August 11.

Akademy will start with the conference on the weekend, August 11-12. I was in the program committee this year and I think we have put together an exciting program. You will see what's going on in KDE, what the community is doing on their goals of privacy, community onboarding, and productivity, hear about the activities of KDE e.V., get to know some of the students who work as part of one of the mentoring programs such as the Google Summer of Code, and much more.

It's a special honor to me to present the Akademy Awards this year together with my fellow award winners from last year. It was hard to choose because there are so many people who do great stuff in KDE. But we have identified a set of people who definitely deserve this prize. Join us at the award ceremony to find out who they are.

Being at Akademy is always special. It's such an amazing group of people hold together by a common idea, culture, and passion. You could never hire such a fantastic group. So I feel lucky that I got and took the opportunity to work with many of these people over the years.

It's also very rewarding to see new people join the community. Akademy always has this special mix of KDE dinosaurs, the young fresh people who just joined, and everything in between. The mentoring KDE does with great care and enthusiasm pays off, with interest.

Vienna is calling. I'll quickly answer the call. See you there.

A hash table re-hash

Hash tables! They're everywhere. They're also pretty boring, but I've had GLib issue #1198 sitting around for a while, and the GNOME move to GitLab resulted in a helpful reminder (or two) being sent out that convinced me to look into it again with an eye towards improving GHashTable and maybe answering some domain-typical questions, like "You're using approach X, but I've heard approach Y is better. Why don't you use that instead?" and "This other hash table is 10% faster in my extremely specific test. Why is your hash table so bad?".

And unfairly paraphrased as those questions may be, I have to admit I'm curious too. Which means benchmarks. But first, what exactly makes a hash table good? Well, it depends on what you're looking for. I made a list.

A miserable pile of tradeoffs

AKA hard choices. You have to make them.

Simple keys vs. complex keys: The former may be stored directly in the hash table and are quick to hash (e.g. integers), while the latter may be stored as pointers to external allocations requiring a more elaborate hash function and additional memory accesses (e.g. strings). If you have complex keys, you'll suffer a penalty on lookups and when the hash table is resized, but this can be avoided by storing the generated hash for each key. However, for simple keys this is likely a waste of memory.

Size of the data set: Small data sets may fit entirely in cache memory. For those, a low instruction count can be beneficial, but as the table grows, memory latency starts to dominate, and you'll get away with more complex code. The extra allowance can be used to improve cache efficiency, perhaps with bucketization or some other fancy scheme. If you know the exact size of the data set in advance, or if there's an upper bound and memory is not an issue, you can avoid costly resizes.

Speed vs. memory generally: There are ways to trade off memory against speed directly. Google Sparsehash is an interesting example of this; it has the ability to allocate the table in small increments using many dynamically growing arrays of tightly packed entries. The arrays have a maximum size that can be set at compile time to yield a specific tradeoff between access times and per-entry memory overhead.

Distribution robustness: A good hash distribution is critical to preventing performance oopsies and, if you're storing untrusted input, thwarting deliberate attacks. This can be costly in the average case, though, so there's a gradient of approaches with power-of-two-sized tables and bitmask moduli at the low end, more elaborate hash functions and prime moduli somewhere in the middle, and cryptographically strong, salted hashes at the very high end. Chaining tables have an additional advantage here, since they don't have to deal with primary clustering.

Mode of operation: Some tables can do fast lookups, but are slower when inserting or deleting entries. For instance, a table implementing the Robin Hood probing scheme with a high load factor may require a large number of entries to be shifted down to make room for an insertion, while lookups remain fast due to this algorithm's inherent key ordering. An algorithm that replaces deleted entries with tombstones may need to periodically re-hash the entire table to get rid of those. Failed lookups can be much slower than successful ones. Sometimes it makes sense to target specific workloads, like the one where you're filtering redundant entries from a dataset and using a hash table to keep track of what you've already seen. This is pretty common and requires insertion and lookup to be fast, but not deletion. Finally, there are more complex operations with specific behavior for key replacement, or iterating over part of the dataset while permuting it somehow.

Flexibility and convenience: Some implementations reserve part of the keyspace for internal use. For instance, Google Sparsehash reserves two values, one for unused entries and one for tombstones. These may be -1 and -2, or perhaps "u" and "t" if your keys are strings. In contrast, GHashTable lets you use the entire keyspace, including storing a value for the NULL key, at the cost of some extra bookkeeping memory (basically special cases of the stored hash field — see "complex keys" above). Preconditions are also nice to have when you slip up; the fastest implementations may resort to undefined behavior instead.

GC and debugger friendliness: If there's a chance that your hash table will coexist with a garbage collector, it's a good idea to play nice and clear keys and values when they're removed from the table. This ensures you're not tying up outside memory by keeping useless pointers to it. It also lets memory debuggers like Valgrind detect more leaks and whatnot. There is a slight speed penalty for doing this.

Other externalities: Memory fragmentation, peak memory use, etc. goes here. Open addressing helps with the former, since the hash table then only makes a few big allocations which the allocator can satisfy with mmap() and simply munmap() when they're not needed anymore. Chaining hash tables make lots of heap allocations, which can get interspersed with other allocations leaving tiny holes all over when freed. Bad!

A note on benchmarks

This isn't the first time, or the second time, or likely even the 100th time someone posts a bunch of hash table benchmarks on the Internet, but it may be the second or third time or so that GHashTable makes an appearance. Strange maybe, given its install base must number in the millions — but on the other hand, it's quite tiny (and boring). The venerable hash table benchmarks by Nick Welch still rule the DuckDuckGo ranking, and they're useful and nice despite a few significant flaws: Notably, there's a bug that causes the C++ implementations to hash pointers to strings instead of the strings themselves, they use virtual size as a measure of memory consumption, and they only sample a single data point at the end of each test run, so there's no intra-run data.

He also classifies GHashTable as a "Joe Sixpack" of hash tables, which is uh… pretty much what we're going for! See also: The Everyman's Hash Table (with apologies to Philip).

Anyway. The first issue is easily remedied by using std::string in the C++ string tests. Unfortunately, it comes with extra overhead, but I think that's fair when looking at out-of-the-box performance.

The second issue is a bit murkier, but it makes sense to measure the amount of memory that the kernel has to provide additional physical backing for at runtime, i.e. memory pages dirtied by the process. This excludes untouched virtual memory, read-only mappings from shared objects, etc. while still capturing the effects of allocator overhead and heap fragmentation. On Linux, it can be read from /proc/<pid>/smaps as the sum of all Private_Dirty and Swap fields. However, polling this file has a big impact on performance and penalizes processes with more mappings unfairly, so in the end I settled on the AnonRSS field from /proc/<pid>/status, which works out to almost the same thing in practice, but with a lower and much more fair penalty.

In order to provide a continuous stream of samples, I wrote a small piece of C code that runs each test in a child process while monitoring its output and sampling AnonRSS a hundred times or so per second. Overkill, yes, but it's useful for capturing those brief memory peaks. The child process writes a byte to stdout per 1000 operations performed so we can measure progress. The timestamps are all in wall-clock time.

The tests themselves haven't changed that much relative to Welch's, but I added some to look for worst-case behavior (spaced integers, aging) and threw in khash, a potentially very fast C hash table. I ran the below benchmarks on an Intel i7-4770 Haswell workstation. They should be fairly representative of modern 64-bit architectures.

Some results

As you may have gathered from the above, it's almost impossible to make an apples-to-apples comparison. Benchmarks don't capture every aspect of performance, and I'm not out to pick on any specific implementation, YMMV, etc. With that in mind, we can still learn quite a bit.

"Sequential" here means {1, 2, …}. The integer tests all map 64-bit integers to void *, except for the Python one, which maps PyLong_FromLong() PyObjects to a single shared PyObject value created in the same manner at the start of the test. This results in an extra performance hit from the allocator and type system, but it's a surprisingly good showing regardless. Ruby uses INT2FIX() for both, which avoids extra allocations and makes for a correspondingly low memory overhead. Still, it's slow in this use case. GHashTable embeds integers in pointers using GINT_TO_POINTER(), but this is only portable for 32-bit integers.

When a hash table starts to fill up, it must be resized. The most common way to do this is to allocate the new map, re-inserting elements from the old map into it, and then freeing the old map. Memory use peaks when this happens (1) because you're briefly keeping two maps around. I already knew that Google Sparsehash's sparse mode allows it to allocate and free buckets in small increments, but khash's behavior (2) surprised me — it realloc()s and rearranges the key and value arrays in-place using an eviction scheme. It's a neat trick that's probably readily applicable in GHashTable too.

Speaking of GHashTable, it does well. Suspiciously well, in fact, and the reason is g_direct_hash() mapping input keys {1, 2, …} to corresponding buckets {1, 2, …} hitting the same cache lines repeatedly. This may sound like a good thing, but it's actually quite bad, as we'll see later in this post. Normally I'd expect khash to be faster, but its hash function is not as cache-friendly:

#define kh_int64_hash_func(key) (khint32_t)((key)>>33^(key)^(key)<<11)

Finally, it's worth mentioning Boost's unique allocation pattern (3). I don't know what's going on there, but if I had to guess, I'd say it keeps supplemental map data in an array that can simply be freed just prior to each resize.

This is essentially the same plot, but with the time dimension replaced by insertion count. It's a good way to directly compare the tables' memory use over their life cycles. Again, GHashTable looks good due to its dense access pattern, with entries concentrated in a small number of memory pages.

Yet another way of slicing it. This one's like the previous plot, but the memory use is per item held in the table. The fill-resize cycles are clearly visible. Sparsehash (sparse) is almost optimal at ~16 bytes per item, while GHashTable also stores its calculated hashes, for an additional 4 bytes.

Still noisy even after gnuplot smoothing, this is an approximation of the various tables' throughput over time. The interesting bits are kind of squeezed in there at the start of the plot, so let's zoom in…

Hash table operations are constant time, right? Well — technically yes, but if you're unlucky and your insertion triggers a resize, you may end up waiting for almost as long as all the previous insertions put together. If you need predictable performance, you must either find a way to set the size in advance or use a slower-and-steadier data structure. Also noteworthy: Sparsehash (dense) is by far the fastest at peak performance, but it struggles a bit with resizes and comes in second.

This one merits a little extra explanation: Some hash tables are fast and others are small, but how do you measure overall resource consumption? The answer is to multiply time by memory, which gets you a single dimension measured in byte-seconds. It's more abstract, and it's not immediately obvious if a particular Bs measurement is good or bad, but relatively it makes a lot of sense: If you use twice as much memory as your competitor, you can make up for it by being twice as fast. Since both resources are affected by diminishing returns, a good all-rounder like GHashTable should try to hit the sweet spot between the two.

Memory use varies over time, and consequently it's not enough to multiply the final memory consumption by total run time. What you really want is the area under the graph in the first plot (memory use over time), and you get there by summing up all the little byte-second slices covered by your measurements. You plot the running sum as you sweep from left to right, and the result will look like the above.

It's not enough to just insert items, sometimes you have to delete them too. In the above plot, I'm inserting 20M items as before, and then deleting them all in order. The hash table itself is not freed. As you can probably tell, there's a lot going on here!

First, this is unfair to Ruby, since I suspect it needs a GC pass and I couldn't find an easy way to do it from the C API. Sorry. Python's plot is weird (and kind of good?) — it seems like it's trimming memory in small increments. In GLib land, GHashTable dutifully shrinks as we go, and since it keeps everything in a handful of big allocations that can be kept in separate memory maps, there is minimal heap pollution and no special tricks needed to return memory to the OS. Sparsehash only shrinks on insert (this makes it faster), so I added a single insert after the deletions to help it along. I also put in a malloc_trim(0) without which the other C++ implementations would be left sitting on a heap full of garbage — but even with the trim in, Boost and std::unordered_map bottom out at ~200MB in use. khash is unable to shrink at all; there's a TODO in the code saying as much.

You may have noticed there are horizontal "tails" on this one — they're due to a short sleep at the end of each test to make sure we capture the final memory use.

Another insertion test, but instead of a {1, 2, …} sequence it's now integers pseudorandomly chosen from the range [0 .. 2²⁸-1] with a fixed seed. Ruby performs about the same as before, but everyone else got slower, putting it in the middle of the pack. This is also a more realistic assessment of GHashTable. Note that we're making calls to random() here, which adds a constant overhead — not a big problem, since it should affect everyone equally and we're not that interested in absolute timings — but a better test might use a pregenerated input array.

GHashTable is neck-and-neck with Sparsehash (dense), but they're both outmatched by khash.

With spaced integers in the sequence {256, 512, 768, …}, the wheels come off Sparsehash and khash. Both implementations use table sizes that are powers of two, likely because it makes the modulo operation faster (it's just a bitmask) and because they use quadratic probing, which is only really efficient in powers of two. The downside is that integers with equal low-order bits will be assigned to a small number of common buckets forcing them to probe a lot.

GHashTable also uses quadratic probing in a power-of-two-sized table, but it's immune to this particular pattern due to a twist: For each lookup, the initial probe is made with a prime modulus, after which it switches to a bitmask. This means there is a small number of buckets unreachable to the initial probe, but this number is very small in practice. I.e. for the first few table sizes (8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256), the number of unreachable buckets is 1, 3, 1, 3, 1, and 5. Subsequent probing will reach these.

So how likely is this kind of key distribution in practice? I think it's fairly likely. One example I can think of is when your keys are pointers. This is reasonable enough when you're keeping sets of objects around and you're only interested in knowing whether an object belongs to a given set, or maybe you're associating objects with some extra data. Alignment ensures limited variation in the low-order key bits. Another example is if you have some kind of sparse multidimensional array with indexes packed into integer keys.

Total resource consumption is as you'd expect. I should add that there are ways around this — Sparsehash and khash will both let you use a more complex hash function if you supply it yourself, at the cost of lower performance in the general case.

Yikes! This is the most complex test, consisting of populating the table with 20M random integers in the range 0-20M and then aging it by alternatingly deleting and inserting random integers for another 20M iterations. A busy database of objects indexed by integer IDs might look something like this, and if it were backed by GHashTable or Sparsehash (sparse), it'd be a painfully slow one. It's hard to tell from the plot, but khash completes in only 4s.

Remember how I said GHashTable did suspiciously well in the first test? Well,

We're paying the price. When there are a lot of keys smaller than the hash table modulus, they tend to concentrate in the low-numbered buckets, and when tombstones start to build up it gets clogged and probes take forever. Fortunately this is easy to fix — just multiply the generated hashes by a small, odd number before taking the modulo. The compiler reduces the multiplication to a few shifts and adds, but cache performance suffers slightly since keys are now more spread out.

On a happier note…

All the tests so far have been on integer keys, so here's one with strings of the form "mystring-%d" where the decimal part is a pseudorandomly chosen integer in the range [0 .. 2³¹-1] resulting in strings that are 10-19 bytes long. khash and GHashTable, being the only tables that use plain C strings, come out on top. Ruby does okay with rb_str_new2(), Python and QHash are on par using PyDict_SetItemString() and QString respectively. The other C++ implementations use std::string, and Sparsehash is really not loving it. It almost looks like there's a bug somewhere — either it's copying/hashing the strings too often, or it's just not made for std::string. My impression based on a cursory search is that people tend to write their own hash functions/adapters for it.

GHashTable's on its home turf here. Since it stores the calculated hashes, it can avoid rehashing the keys on resize, and it can skip most full key compares when probing. Longer strings would hand it an even bigger advantage.

Conclusion

This post is really all about the details, but if I had to extract some general lessons from it, I'd go with these:

- Tradeoffs, tradeoffs everywhere.

- Worst-case behavior matters.

- GHashTable is decent, except for one situation where it's patently awful.

- There's some room for improvement in general, cf. robustness and peak memory use.

My hash-table-shootout fork is on Github. I was going to go into detail about potential GHashTable improvements, but I think I'll save that for another post. This one is way too long already. If you got this far, thanks for reading!

Update: There's now a follow-up post.

GSoC Half Way Throug

As you may already know, openSUSE participates again in GSoC, an international program that awards stipends to university students who contribute to real-world open source projects during three months in summer. Our students started working already two months ago. Ankush, Liana and Matheus have passed the two evaluations successfully and they are busy hacking to finish their projects. Go on reading to find out what they have to say about their experience, their projects and the missing work for the few more weeks. :grinning:

Ankush Malik

Ankush is improving people collaboration in the Hackweek tool and he has already made many great contributions like the emoticons, similar project section and notifications features. In fact, the Hackweek 17 was just last week, so in the last days a lot of people have already been using these great new features. There were a lot of good comments about his work! :cupid: and we also received a lot of feedback, as you can for example see in the issues list.

But even more important than all the functionality, is all Ankush is learning while coding and working with his mentors and the openSUSE community, such as working with AJAX in Ruby on Rails, good coding practices and better coding style.

The last part of his project will include some more new features. If you want to find out more about his project and the challenges that Ankush expects to have, read his interesting blog post: https://medium.com/@ankushmalik631/how-my-gsoc-project-is-going-4942614132a2

Xu Liana

Liana is working on integrating Cloud Pinyin (the most popular input method in China) on ibus-libpinyin. For her, GSoC is being an enjoyable learning process full of challenges. With the help of her mentors she has learnt about autotools and she builds now her code without graphical build tools :muscle: For the few more weeks, she plans to learn about algorithmics that are useful for the project and, after finish the coding part, she would like to go deeper in the fundamentals of compiling. Read it from her owns word in her blog post: https://liana.hillwoodhome.net/2018/07/14/the-first-half-of-the-project-during-gsoc-libpinyin

Matheus de Sousa Bernardo

Matheus is working in Trollolo, a cli-tool which helps teams using Trello to organize their work. He has been mainly focused on the restructuring of commands and the incomplete backup feature. The discussion with his mentors made him take different implementation paths than the ones he had in mind at the beginning, learning the importance of keeping things simple. It has been complicated for Matheus to find time for both the GSoC project and his university duties. But he still has some more weeks to implement the more challenging feature, the automation of Trollolo! :boom:

Check his blog post with more details about the project: https://matheussbernardo.me/gsoc/2018/07/08/midterm

I hope you enjoyed reading about the work and experiences of the openSUSE students and mentors. Keep tuned as there are still some more hacking weeks and the students will write a last blog post summarizing their GSoC experience. :wink:

rriemann

rriemann Member

Member