A failing test for Christmas

It seems I have really well behaved on 2017, because Santa Claus brought me a failing test for Christmas. :stuck_out_tongue_winking_eye: I found out a piece of code, that was only wrong from 26th to 31st December. :christmas_tree:

The code

Imagine you want to write a Ruby method for a Rails project, where you want to get all the users of the database that have birthday today or in the next 6 days, given that the birth date is stored in the database for all users. How would you do it?

As for the birthday you don’t care of the year of the dates, you could just replace the users’ birth years by the current one and check if they are in the range you want. So, the code I found looked something like:

def next_birthdays_1(number_days)

today = Date.current

User.select do |user|

(today..today + number_days.days).cover?(user.birthday.change(year: today.year))

end

end

This code seemed to work. There was even a test for it and it passed. But on 26th December, the new year coming broke the test, showing that the code was wrong. For example, if a user was born on 01/01/1960, the range 26/12/2017 to 01/01/2018 doesn’t cover 01/01/2017.

Let’s fix the code! :muscle:

We can stop trying to be too smart and just testing if the day and month of the users birth dates match any of the dates in the range:

def next_birthdays_2(number_days)

today = Date.current

select do |user|

(today..today + number_days.days).any? do |date|

user.birthday.strftime('%d%m') == date.strftime('%d%m')

end

end

end

This code works and it works the whole year. :rofl: But what happens if now we want to get the birthdays of the next 30 days and we have for example 30000 users. Would this code be efficient enough? Can we do it better? :thinking:

One thing I come up with was reusing the original idea, that we do not care about the year, but using two dates instead. So to know if a user was born in 01/01/1960, the range 26/12/2017 to 01/01/2018 should cover 01/01/2017 or 01/01/2018. As for both dates, the birthday is the same one. So, we can write this as follows:

def next_birthdays_3(number_days)

today = Date.current

User.select do |user|

(today..today + number_days.days).cover?(user.birthday.change(year: today.year)) ||

(today..today + number_days.days).cover?(user.birthday.change(year: (today.year + 1)))

end

end

But this method is wrong, as it has a problem which also had the first one. What happens if the user was born the 29th February of a leap year? birthday.change(year: 2017) would fail, as 2017 was not a leap year and 29th February of 2017 doesn’t exist. :see_no_evil: But we can do a smart trick to keep using the same idea: using string comparison without taking into account the leap years! :smile: It would look like:

def next_birthdays_4(number_days)

today = Date.current

today_str = today.strftime('%Y%m%d')

limit = today + number_days.days

limit_str = limit.strftime('%Y%m%d')

User.select do |user|

birthday_str = user.birthday.strftime('%m%d')

birthday_today_year = "#{today.year}#{birthday_str}"

birthday_limit_year = "#{limit.year}#{birthday_str}"

birthday_today_year.between?(today_str, limit_str) || birthday_limit_year.between?(today_str, limit_str)

end

end

Note that this method is not equivalent to next_birthdays_2, as it returns the users that have birthday in 29th February if the range includes this date even if it is not a leap year. But I would say this is an advantage, as we do not want that the people who were born on 29th February do not have birthday party some years. :wink:

But remember that this is a Rails project, so we can do it even better if we reuse this idea to build an SQL query! :tada: For example, for PostgreSQL 9.4:

def next_birthdays_5(number_days)

today = Date.current

today_str = today.strftime('%Y%m%d')

limit = today + number_days.days

limit_str = limit.strftime('%Y%m%d')

User.where(

"(('#{today.year}' || to_char(birthday, 'MMDD')) between '#{today_str}' and '#{limit_str}')" \

'or' \

"(('#{limit.year}' || to_char(birthday, 'MMDD')) between '#{today_str}' and '#{limit_str}')"

)

end

As it already happened in next_birthdays_4, this method returns the users that have birthday in 29th February if the range includes this date even if it is not a leap year.

In PostgreSQL we have the Date type and from PostgreSQL 9.2 also daterange which we could have use to make this query more efficient. This would have been equivalent to next_birthdays_3 and would have had the same problem, it fails with leap years.

Efficiency

And now it is time to try it! Let check how efficient are the methods number 2, 4 and 5 (as the the other two doesn’t work properly as we had already analysed).

I have created 30000 users with different birth dates using Faker. I have executed the different methods to know the number of people with birthday in the next 31 days and I have measured the execution time using Benchmark.measured. Those are elapsed real times for every of the method in my computer:

-

next_birthdays_2(30)~ 3.3 seconds -

next_birthdays_4(30)~ 0.9 seconds -

next_birthdays_5(30)~ 0.0003 seconds

Take into account that next_birthdays_2 is much more affected by the number of days than the other two methods. But even for 6 days it is really slow, as the elapsed real time in my computer for next_birthdays_2(6) is arround 1.45 seconds.

Conclusion

And the funny thing of all this is that, as it is already 2018, even if I haven’t fixed the test yet, the Christmas failing test doesn’t fail anymore. :joy: This is because we forgot to add test cases for the limit cases and help us to learn that when working with dates we have to pay special attention to the changes of year and to the 29th of February and the leap years. And of course all this should be properly tested.

Another thing we can learn from the post is that as Rails developers we should never forget that the database queries are always way more efficient than the Ruby code we write.

Last but not least, we may consider if the effort to write a method worths the time you need to invest to write it. For example, in this case we could have considered if we could have lived with a method which returns the birthdays this month, which is much easier to implement, instead of this more complicate option. Or, if we do not expect that out application has a lot of users, we could have even used next_birthdays_2.

And if you want to take a look at the original code which inspired this post, you can find it in the following PR: https://github.com/openSUSE/agile-team-dashboard/pull/100

Happy new year! :christmas_tree: :champagne:

An Introduction To Rendering In React

In this post I want to talk about how React renders components, and how it tries to improve performance by using its reconciliation algorithm to only update the parts of the DOM that need updating. This is not meant to be an introduction to React, but I will quickly go over some of the relevant foundation concepts in the next section.

What Is React?

React is an open source JavaScript library created by Facebook to address some of the needs they had when dealing with the development of the Facebook website. React has played an important role in the evolution of JavaScript Frameworks because it is responsible for popularizing the Component Based Architecture (CBA) paradigm. An important distinction between React and frameworks like Angular is that React is only a library. For example, React does not provide its own routing or HTTP libraries. To perform these type of tasks in React developers have to rely on other libraries like Redux and the Fetch API.

Since React is simply a library, it can be used in existing projects very easily:

While it is nice to be able to use React with pure JavaScript things can get hairy when writing a very large app. For this reason you may find it easier to use JSX, an alternative way of writing React code. JSX essentially allows you to combine HTML and JavaScript syntax together to make it easier to mange the code. The same example above can be written using JSX (more on it below):

Component Based Architecture (CBA)

In this article I am not going to go into detail about CBA (there are a ton of great articles already available about that) but I will just explain some of the motivation as to why Reacts approach is useful for developers. When writing code using a framework like AngularJS, you have to use Controllers and Views to create your application. Controllers house the logic (JS) for your application while the Views house the UI elements (HTML). This separation of logic from UI allows for one to be changed without significantly impacting the other. For example if you need to change the logic in a function, this can be done without having to rewrite any of the UI. One of the problems with this approach however, is that it makes it difficult to modify a specific part of the UI without also having to modify other parts of the interface and logic.

What makes CBA different is that in CBA the logic and UI are kept together, causing the two to be coupled to each other. The goal of CBA is to encapsulate portions of an interface into self contained units called components. The use of encapsulation allows a component to be changed without the developer having to modify any other component. Another major benefit of components is that they are reusable, which is key to writing good code in React.

JSX

JSX works as a syntax extension for JavaScript that combines templating languages with JavaScript. While JSX is optional to use in React, it is much more elegant than using pure JavaScript so I prefer using it when building React applications. Just like XML, JSX elements can have names, attributes and children. Values enclosed in curly braces are interpreted as JavaScript expressions which you can use to substitute a hard coded value with a variable or evaluation.

When React renders JSX (more on this later) it will convert the JSX elements into JavaScript and then use them to create the DOM. An interesting property of JSX is that it prevents injection attacks by converting everything into a string before rendering it. This ensures that a malicious user cannot execute XSS attacks using your application.

Unidirectional Data Flow

Another fundamental concept in React is the Unidirectional Data Flow which is how React propagates updates to components. Actions in the UI lead to the state of components being updated which in turn will cause the view to update to reflect these new changes.

Parent components can pass variables to their child components using props to provide them with the necessary context in which to render. Note that the arrows are not bidirectional, this is because components cannot update their parents, they can only receive updates from them.

The Initial Render

All React applications start at a root DOM node that marks the portion of the DOM that will be managed by React. You add child components to this node using React to get your application to look and behave the way you desire.

JSX

When React is called to render the component tree it will first need the JSX in your code to be converted into pure JavaScript. This can be achieved by making use of Babel. You may already be familiar with the Babel project for its transpiling capabilities, but it is also be used to convert the JSX you write into pure JavaScript. To see this in action you can check out this live demo on the Babel website. On the left is the JSX and on the right is the resulting JavaScript.

Lifecycle Methods

React comes with some lifecycle methods that you can use to update and control the application state. You can find out more about how and when to use them by reading this great article by Bartosz Szczeciński.

By default, React will re-render all child components of any component that itself has to re-render. This behavior may not always be ideal, for example when re-rendering the component requires performing costly calculations. The shouldComponentUpdate lifecycle method can be used to address this concern. By default it will always return true but you can add logic so that it only returns true under specific conditions. Note that this lifecycle method does not apply to when a component has its internal state changed using setState() which will still cause a re-render even if the shouldComponentUpdate method always returns false.

Updating Components

Once React has completed the initial render for your application it waits for one of two events before triggering an update for a component. Either the internal state of the component changes, or the props being passed into the component change.

Internal state of a component can be changed by calling the setState() function. The important thing to remember about setState() is that it is not executed immediately, as React may delay the state update.

Think of setState() as a request rather than an immediate command to update the component. For better perceived performance, React may delay it, and then update several components in a single pass. React does not guarantee that the state changes are applied immediately.

— React Docs

Props, unlike state, cannot be modified by the component they are being passed into. Components must instead rely on their parent to provide updates to the props. These updates can occur under two situations, either the parent will update the props due to some internal state change or the child will call a function passed down by the parent that updates some state in the parent which in turn will update the props of the component causing it to re-render. Below is an example of how a child component would call a function passed down by its parent, note that it assumes component C did not need to be re-rendered (this is not always the case).

Reconciliation

When React has to perform updates to a component it attempts to improve performance by only updating what needs to be updated. The way React accomplishes this is by using its ‘diffing’ or reconciliation algorithm. According to the React docs, there are two assumptions that React makes when it comes to reconciliation:

- Two elements of different types will always produce different trees

- Developers can hint which child elements are stable across different renders using a key prop

The reconciliation algorithm behaves differently depending on what type of root element it has to re-render.

Elements Of Different Types

If the new element is a different type of element than the old element (ex. changing from <span> to <h1>) then React has to perform a full rebuild of the tree. This means that it will destroy the old tree and build a new one from scratch. Note that since the old tree is destroyed, any state associated with it will also be gone. When the old nodes are destroyed, the componentWillUnmount lifecycle method will be invoked. As the new tree is created, the new nodes will call the componentWillMount and componentDidMount lifecycle methods.

Elements Of The Same Type

If the new element is the same type as the old element then React will keep the same DOM node and instead only updates the attributes that have changed. When the props are changed to match the new element, the componentWillReceiveProps and the componentWillUpdate lifecycle methods are called. For example if you update the style for an element, React knows to only update the specific properties of the CSS that changed. Note that since the node is not destroyed any state associated with the old node is still available. Once React has updated the node, it will recurse on its children.

Recursing On Children

When the reconciliation algorithm recurses on the children of a node, React iterates over a list of both the old and new children. There is a good explanation of how this works in the React docs. As mentioned in the docs, there may be performance issues if the new child is not appended to the list as React will not know what did and did not change. To avoid this issue you can use the key prop to give the element a unique ID so React can determine what actually changed.

Conclusion

Hopefully that was a useful explanation of how React does rendering of components and why its important to be aware of how you can improve its performance by following certain coding practices. If you have any questions or feedback, please leave a message in the comments.

An Introduction To Rendering In React was originally published in Information & Technology on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

PostmarketOS and digital cameras

GNOME.Asia Summit 2017

It’s import to get support in university when we want to promote open source and freeware all the time.

( https://www.flickr.com/groups/gnomeasia2017/pool )

Librsvg 2.40.20 is released

Today I released librsvg 2.40.20. This will be the last release in the 2.40.x series, which is deprecated effectively immediately.

People and distros are strongly encouraged to switch to librsvg 2.41.x as soon as possible. This is the version that is implemented in a mixture of C and Rust. It is 100% API and ABI compatible with 2.40.x, so it is a drop-in replacement for it. If you or your distro can compile Firefox 57, you can probably build librsvg-2.41.x without problems.

Some statistics

Here are a few runs of loc — a tool to count lines of code — when run on librsvg. The output is trimmed by hand to only include C and Rust files.

This is 2.40.20:

-------------------------------------------------------

Language Files Lines Blank Comment Code

-------------------------------------------------------

C 41 20972 3438 2100 15434

C/C++ Header 27 2377 452 625 1300

This is 2.41.latest (the master branch):

-------------------------------------------------------

Language Files Lines Blank Comment Code

-------------------------------------------------------

C 34 17253 3024 1892 12337

C/C++ Header 23 2327 501 624 1202

Rust 38 11254 1873 675 8706

And this is 2.41.latest *without unit tests*,

just "real source code":

-------------------------------------------------------

Language Files Lines Blank Comment Code

-------------------------------------------------------

C 34 17253 3024 1892 12337

C/C++ Header 23 2327 501 624 1202

Rust 38 9340 1513 610 7217

Summary

Not counting blank lines nor comments:

-

The C-only version has 16734 lines of C code.

-

The C-only version has no unit tests, just some integration tests.

-

The Rust-and-C version has 13539 lines of C code, 7217 lines of Rust code, and 1489 lines of unit tests in Rust.

As for the integration tests:

-

The C-only version has 64 integration tests.

-

The Rust-and-C version has 130 integration tests.

The Rust-and-C version supports a few more SVG features, and it is A LOT more robust and spec-compliant with the SVG features that were supported in the C-only version.

The C sources in librsvg are shrinking steadily. It would be

incredibly awesome if someone could run some git filter-branch magic

with the loc tool and generate some pretty graphs of source

lines vs. commits over time.

Librsvg moves to Gitlab

Librsvg now lives in GNOME's Gitlab instance. You can access it here.

Gitlab allows workflows similar to Github: you can create an account there, fork the librsvg repository, file bug reports, create merge requests... Hopefully this will make it nicer for contributors.

In the meantime, feel free to take a look!

This is a huge improvement for GNOME's development infrastructure. Thanks to Carlos Soriano, Andrea Veri, Philip Chimento, Alberto Ruiz, and all the people that made the move to Gitlab possible.

A mini-rant on the lack of string slices in C

Porting of librsvg to Rust goes on. Yesterday I started porting the

C code that implements SVG's <text> family of elements. I have also

been replacing the little parsers in librsvg with Rust code.

And these days, the lack of string slices in C is bothering me a lot.

What if...

It feels like it should be easy to just write something like

typedef struct {

const char *ptr;

size_t len;

} StringSlice;

And then a whole family of functions. The starting point, where you slice a whole string:

StringSlice

make_slice_from_string (const char *s)

{

StringSlice slice;

assert (s != NULL);

slice.ptr = s;

slice.len = strlen (s);

return slice;

}

But that wouldn't keep track of the lifetime of the original string. Okay, this is C, so you are used to keeping track of that yourself.

Onwards. Substrings?

StringSlice

make_sub_slice(StringSlice slice, size_t start, size_t len)

{

StringSlice sub;

assert (len <= slice.len);

assert (start <= slice.len - len); /* Not "start + len <= slice.len" or it can overflow. */

/* The subtraction can't underflow because of the previous assert */

sub.ptr = slice.ptr + start;

sub.len = len;

return sub;

}

Then you could write a million wrappers for g_strsplit() and

friends, or equivalents to them, to give you slices instead of C

strings. But then:

-

You have to keep track of lifetimes yourself.

-

You have to wrap every function that returns a plain "

char *"... -

... and every function that takes a plain "

char *" as an argument, without a length parameter, because... -

You CANNOT take

slice.ptrand pass it to a function that just expects a plain "char *", because your slice does not include a nul terminator (the'\0byte at the end of a C string). This is what kills the whole plan.

Even if you had a helper library that implements C string slices

like that, you would have a mismatch every time you needed to call a C

function that expects a conventional C string in the form of a

"char *". You need to put a nul terminator somewhere, and if you

only have a slice, you need to allocate memory, copy the slice into

it, and slap a 0 byte at the end. Then you can pass that to a

function that expects a normal C string.

There is hacky C code that needs to pass a substring to another function, so it overwrites the byte after the substring with a 0, passes the substring, and overwrites the byte back. This is horrible, and doesn't work with strings that live in read-only memory. But that's the best that C lets you do.

I'm very happy with string slices in Rust, which work exactly like the

StringSlice above, but &str is actually at the language level and

everything knows how to handle it.

The glib-rs crate has conversion traits to go from Rust strings or

slices into C, and vice-versa. We alredy saw some of those in the

blog post about conversions in Glib-rs.

Sizes of things

Rust uses usize to specify the size of things; it's an unsigned

integer; 32 bits on 32-bit machines, and 64 bits on 64-bit machines;

it's like C's size_t.

In the Glib/C world, we have an assortment of types to represent the sizes of things:

-

gsize, the same assize_t. This is an unsigned integer; it's okay. -

gssize, a signed integer of the same size asgsize. This is okay if used to represent a negative offset, and really funky in the Glib functions likeg_string_new_len (const char *str, gssize len), wherelen == -1means "callstrlen(str)for me because I'm too lazy to compute the length myself". -

int- broken, as in libxml2, but we can't change the API. On 64-bit machines, anintto specify a length means you can't pass objects bigger than 2 GB. -

long- marginally better thanint, since it has a better chance of actually being the same size assize_t, but still funky. Probably okay for negative offsets; problematic for sizes which should really be unsigned. -

etc.

I'm not sure how old size_t is in the C standard library, but it

can't have been there since the beginning of time — otherwise

people wouldn't have been using int to specify the sizes of things.

Hackweek 16 - The YaST Integration Tests II.

Hackweek 16 (0x10)

I spent the previous Hackweek with Cucumber and YaST. It worked quite well but it turned out to be too big step forward and focused on one specific testing framework.

This time I decided to make a smaller step, but make the solution more generic. So instead of having direct Cucumber support in the UI I proposed implementing a generic REST API. The API can be then used by any framework (Cucumber, RSpec…) or it can be used directly by any script or tool.

See also the Hackweek project page.

Implementation

The current solution is based on these two key libraries:

- GNU libmicrohttpd - an embedded HTTP server

- jsoncpp - JSON parser/writer

Both libraries are already included in the openSUSE distributions so it is easy to use them.

Installation

After compiling and installing new libyui, libyui-qt and recompiling

yast2-ycp-ui-bindings (because of ABI changes) you can run any YaST module with

YUI_HTTP_SERVER=14155 environment variable set. Then you can access the REST

API via the port 14115 using curl command. (You can use a different port

number.)

Using the REST API

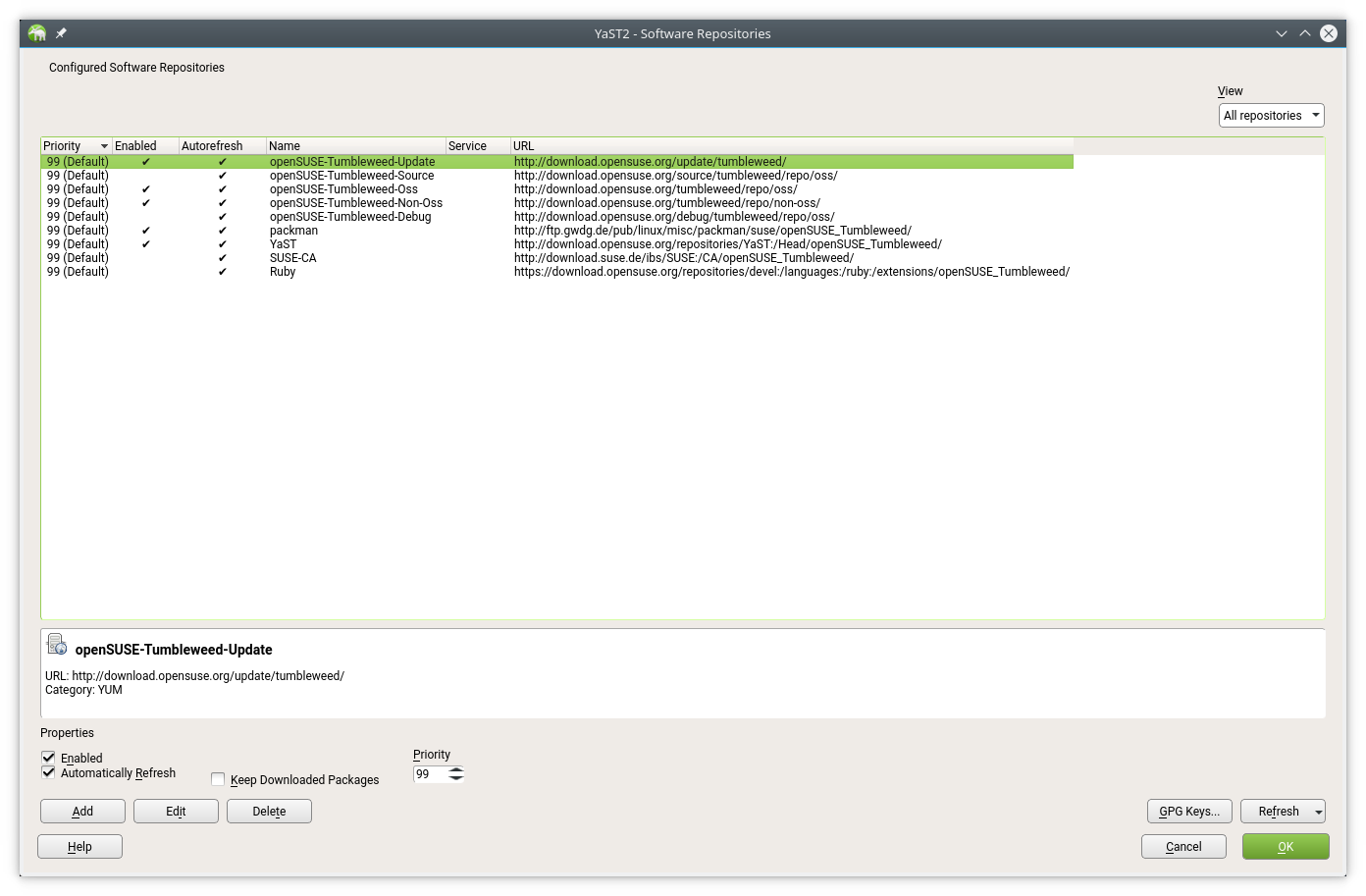

Run the YaST repository manager (as root):

YUI_HTTP_PORT=14155 yast2 repositories

This will start the YaST module as usually, there is no visible change. You can normally use the module, the only change is that the UI now listens on the port 14155 for incoming HTTP requests.

You can access the REST API (root not required) from command line like this:

> # dump the current dialog as a tree

> curl 'http://localhost:14155/dialog'

{

"class" : "YDialog",

"hstretch" : true,

"type" : "wizard",

"vstretch" : true,

"widgets" :

[

{

"class" : "YWizard",

"debug_label" : "Configured Software Repositories",

"hstretch" : true,

"id" : "wizard",

"vstretch" : true,

"widgets" :

[

...

> # dump the current dialog as a simple list (easier iteration, search)

> curl 'http://localhost:14155/widgets'

[

{

"class" : "YDialog",

"hstretch" : true,

"type" : "wizard",

"vstretch" : true

},

{

"class" : "YWizard",

"debug_label" : "Configured Software Repositories",

"hstretch" : true,

"id" : "wizard",

"vstretch" : true

},

...

> # filter widgets by ID

> curl 'http://localhost:14155/widgets?id=enable'

[

{

"class" : "YCheckBox",

"debug_label" : "Enabled",

"id" : "enable",

"label" : "E&nabled",

"notify" : true,

"value" : true

}

]

> # filter widgets by label (as displayed, might be translated!)

> curl 'http://localhost:14155/widgets?label=Priority'

[

{

"class" : "YIntField",

"debug_label" : "Priority",

"hstretch" : true,

"id" : "priority",

"label" : "&Priority",

"max_value" : 200,

"min_value" : 0,

"notify" : true,

"value" : 99

}

]

> # filter widgets by type (all check boxes in this case)

> curl 'http://localhost:14155/widgets?type=YCheckBox'

[

{

"class" : "YCheckBox",

"debug_label" : "Enabled",

"id" : "enable",

"label" : "E&nabled",

"notify" : true,

"value" : true

},

{

"class" : "YCheckBox",

"debug_label" : "Automatically Refresh",

"id" : "autorefresh",

"label" : "Automatically &Refresh",

"notify" : true,

"value" : true

},

{

"class" : "YCheckBox",

"debug_label" : "Keep Downloaded Packages",

"id" : "keeppackages",

"label" : "&Keep Downloaded Packages",

"notify" : true,

"value" : false

}

]

> # and finally do some action - press the [Abort] button and close the module,

> # you can use the same filters as in the queries above

> curl -X POST 'http://localhost:14155/widgets?id=abort&action=press'

To make it cool I have included some inline documentation or help, just open

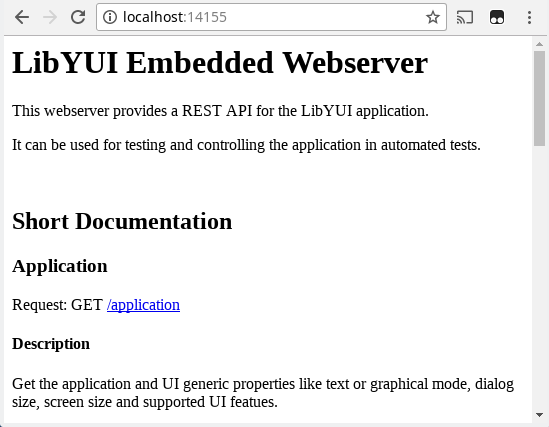

http://localhost:14155 URL in your browser:

Running a Cucumber Test

I have also written a simple set of step definitions for the Cucumber framework. This allows using the REST API in Cucumber integration tests.

Let’s have this example Cucumber test:

Feature: To install the 3rd party packages I must be able to add a new package

repository to the package management.

Background:

# make sure the tested repository does not already exist

When I run `zypper repos --uri`

Then the output should not contain "https://download.opensuse.org/tumbleweed/repo/oss/"

Scenario: Aborting the repository manager keeps the old settings

Given I start the "/usr/sbin/yast2 repositories" application

Then the dialog heading should be "Configured Software Repositories"

When I click button "Add"

Then the dialog heading should be "Add On Product"

When I click button "Next"

Then the dialog heading should be "Repository URL"

When I enter "Tumbleweed OSS" into input field "Repository Name"

And I enter "https://download.opensuse.org/tumbleweed/repo/oss/" into input field "URL"

And I click button "Next"

Then the dialog heading should be "Tumbleweed OSS License Agreement" in 60 seconds

When I click button "Next"

Then the dialog heading should be "Configured Software Repositories"

When I click button "Cancel"

Then a popup should be displayed

And a label including "Abort the repository configuration?" should be displayed

Then I click button "Yes"

And I wait for the application to finish

# verify that the tested repository was NOT added

When I run `zypper repos --uri`

Then the output should not contain "https://download.opensuse.org/tumbleweed/repo/oss/"

If you run it the result would look like this:

Pretty nice isn’t it?

Generic Usage

Because the REST API is implemented on the UI (libyui) level it means that any application using the library can be tested the same way, it is not limited only to YaST. For example it should be very easy to write tests also for the Mageia tools included in the Megeia distribution.

TODO

There are lots of missing features, mainly:

- Return more details in the response, add missing attributes

- Support more actions besides clicking a button or filling an

InputField - Support more UI calls (e.g.

UI.PollInput) - Support the other UIs (ncurses, maybe GTK)

- Support for the package manager widget (implemented in the

libyui-*-pkgsubpackages) - Packaging - make the feature optional (if you do not want to include the web server for security reasons)

- Add more step definitions in the Cucumber wrapper

Optional Features

- User authentication (unauthenticated access is a security hole, but it might be OK when running tests in a sandboxed environment in a trusted network)

- SSL support (securely transfer the current values and set the new values, e.g. the root password)

- IPv6 support (it’s the future, isn’t it?)

- Unix socket support (another kind of user authorization)

Conclusion

The feature is far from being production ready, it is still rather a proof of concept. But it shows that it works well and we can continue in this direction in the future.

Making Rails packaging easier - Part1

One step at a time. Today: Requires

You might have seen that we package rails apps for a while now. We have discourse, gitlab-ce, errbit and our own open build service. I probably forgot an app or 2 here. Anyway if you look at all the spec files e.g. this one. You notice we have to specify the Requires manually.

BuildRequires: %{rubygem rails:5 >= 5.1}

Requires: %{rubygem rails:5 >= 5.1}

This comes with a few problems actually.

KDE’s Goal: Privacy

A world in which everyone has control over their digital life and enjoys freedom and privacy.

This presents a very high-level vision, so a logical follow-up question has been how this influences KDE’s activities and actions in practice. KDE, being a fairly loose community with many separate sub-communities and products, is not an easy target to align to a common goal. A common goal may have very different on each of KDE’s products, for an email and groupware client, that may be very straight-forward (e.g. support high-end crypto, work very well with privacy-respecting and/or self-hosted services), for others, it may be mostly irrelevant (a natural painting app such as Krita simply doesn’t have a lot of privacy exposure), yet for a product such as Plasma, the implications may be fundamental and varied.

So in the pursuit of the common ground and a common goal, we had to concentrate on what unites us. There’s of course Software Freedom, but that is somewhat vague as well, and also it’s already entrenched in KDE’s DNA. It’s not a very useful goal since it doesn’t give us something to strive for, but something we maintain anyway. A “good goal” has to be more specific, yet it should have a clear connection to Free Software, since that is probably the single most important thing that unites us. Almost two years ago, I posed that privacy is Free Software’s new milestone, trying to set a new goal post for us to head for. Now the point where these streams join has come, and KDE has chosen privacy as one of its primary goals for the next 3 to 4 years. The full proposal can be read here.

So in the pursuit of the common ground and a common goal, we had to concentrate on what unites us. There’s of course Software Freedom, but that is somewhat vague as well, and also it’s already entrenched in KDE’s DNA. It’s not a very useful goal since it doesn’t give us something to strive for, but something we maintain anyway. A “good goal” has to be more specific, yet it should have a clear connection to Free Software, since that is probably the single most important thing that unites us. Almost two years ago, I posed that privacy is Free Software’s new milestone, trying to set a new goal post for us to head for. Now the point where these streams join has come, and KDE has chosen privacy as one of its primary goals for the next 3 to 4 years. The full proposal can be read here.

“In 5 years, KDE software enables and promotes privacy”

Privacy, being a vague concept, especially given the diversity in the KDE community needs some explanation, some operationalization to make it specific and to know how we can create software that enables privacy. There are three general focus areas we will concentrate on: Security, privacy-respecting defaults and offering the right tools in the first place.

Security

Improving security means improving our processes to make it easier to spot and fix security problems and avoiding single points of failure in both software and development processes. This entails code review, quick turnaround times for security fixes.

Privacy-respecting defaults

Defaulting to encrypted connections where possible and storing sensible data in a secure way. The user should be able to expect the KDE software Does The Right Thing and protect his or her data in the best possible way. Surprises should be avoided as much as possible, and reasonable expectations should be met with best effort.

Offering the right tools

KDE prides itself for providing a very wide range of useful software. From a privacy point of view, some functions are more important than others, of course. We want to offer the tools that most users need in a way that allows them to lead their life privately, so the toolset needs to be comprehensive and cover as many needs as possible. The tools itself should make it easy and straight-forward to achieve privacy. Some examples:

- An email client allowing encrypted communication

- Chat and instant messenging with state-of-the art protocol security

- Support for online services that can be operated as private instance, not depending on a 3rd party provider

- …

Of course, this is only a small part, and the needs of our userbase varies wildly.

Onwards from here…

In the past, KDE software has come a long way in providing privacy tools, but the tool-set is neither comprehensive, nor is privacy its implications widely seen as critical to our success in this area. Setting privacy as a central goal for KDE means that we will put more focus on this topic and lead to improved tools that allow users to increase their level of privacy. Moreover, it will set an example for others to follow and hopefully increase standards across the whole software ecosystem. There is much work to do, and we’re excited to put our shoulder under it and work on it.

Member

Member Ana06

Ana06