A Simple List Render Optimization For React

Yesterday I was watching a talk by Ben Ilegbodu at React Alicante called Help! My React App is Slowwwww! in which Ben discussed some optimizations developers can make to help improve performance of React applications. He goes over many of the potential bottlenecks that may arise such as unnecessary DOM updates, reconciliation and unnecessary object creation. It’s a really interesting talk and I encourage you to watch it (link below) but what I found most interesting was his first point about unnecessary DOM updates.

When trying to optimize performance of web apps, we can look for actions that are bottlenecks and try to minimize the amount of times the application performs these actions. It turns out updating the DOM is a very time consuming operation. It is in fact so time consuming that React has a process called reconciliation that exists to try and avoid unnecessary updates.

Unfortunately as Ben shows in his talk — and as I will show in this post — there are still situations where reconciliation will not be able to help us. However we don’t need to lose hope because there are some simple tweaks we can make to address the issue.

The 🔑 to Lists

This is a really handy trick you can use to optimize the rendering of list items in React. Suppose you have a page that displays a list of items and is defined as follows:

When the button is clicked, it will add an item to the list. This will then trigger an update to the DOM to display our new item along with all the old items. If we look at the DOM inspector while clicking the button we see the following (orange indicates the node is updating):

See how all the list items are updated? If we think about this for a moment this doesn’t actually seem like an ideal update. Why can’t we just insert the new node without having to update all the other nodes? The reason for this has to do with how we are using the map function in the List component.

See how we are setting the key for each list item as the index? The problem here is that React uses the key to determine if the item has actually changed. Unfortunately since the insertion we are doing happens at the start of the list, the indexes of all items in the list are increased by one. This causes React to think there has been a change to all the nodes and so it updates them all.

To work around this we need to modify the map function to use the unique id of each item instead of the index in the array:

And now when we click the button we see that the new nodes are being added without updating the old ones:

So what’s the lesson?

Always use a unique key when creating lists in React (and the index is not considered unique)!

The Exception ✋

There can be situations where you do not have a truly unique id in your arrays. The ideal solution is to find some unique key which may be derived by combining some values in the object together. However in certain cases — like an array of strings — this cannot be possible or guaranteed. In these cases you must rely on the index to be the key.

So there you have it, a simple trick to optimize list rendering in React! 🎉🏎

If you liked this post be sure to follow this blog, follow me on twitter and my blog on dev.to.

P.S. Looking to contribute to an open source project? Come contribute to Saka, we could use the help! You can find the project here: https://github.com/lusakasa/saka

A Simple List Render Optimization For React 🏎 was originally published in Information & Technology on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Announcing Tumbleweed Snapshots Official Hosting

Adapted from announcement to opensuse-factory mailing list:

Tumbleweed Snapshots, fixed repositories containing previously released versions of Tumbleweed, are now officially hosted on download.opensuse.org! For those not familiar with the Tumbleweed Snapshots concept please see the short introduction video and the presentation I gave at oSC18. The overall concept is to allow Tumbleweed to be consumed as short-lived distributions that can be utilized after a new snapshot is published. The two primary benefits are not having to update just to install new packages and being able to sit on an older snapshot when avoiding problematic package updates. The latter working best with snapper rollbacks as it allows for normal system operation after rolling back.

Given the proper method for updating between snapshots is zypper dup instead of zypper up which is normally reserved for updating between major releases of the distribution, like Leap, keeping the previous repositories and switching between them with the use of dup is quite natural. Given the latest snapshot is accessible and zypper operates normally there are no down-sides to this approach while providing some important advantages. If you have not already tried them I would encourage you to do so. Many users are already updating Tumbleweed once a week and thus perfectly align with the design of snapshots.

The installation step and basic usage is documented in the tumbleweed-cli README. No additional resources are utilized on the local machine. If for whatever reason you want to go back just run tumbleweed uninit to restore the default repository setup.

If you are already using Tumbleweed Snapshots and would like to switch to the official hosting a migration command is provided in tumbleweed-cli 0.3.0 which will be included in Tumbleweed shortly. As a side-note, bash completion is also provided!

Once running version 0.3.0 (run tumbleweed --version to see which is installed), simply run tumbleweed migrate. Keep in mind the official hosting only provides 10 snapshots while my personal hosting on S3 provides 50. The count will hopefully be increased in the future, but given how long it has taken to get this far it may be some time. Additionally, my AWS hosting has a CDN setup and will likely remain faster until mirrors decide to host the snapshots. Based on feedback and how things progress I will decide when to stop hosting on AWS, but it will be announced and the tumbleweed-cli will be changed to auto-migrate.

For those interested, the difference in storage usage can be compared on metrics.opensuse.org.

Making Tumbleweed Snapshots the default is likely worth considering once everything settles and an appropriate level of adoption by mirrors is reached.

It is encouraging to see the enthusiastic discussions about Tumbleweed Snapshots in IRC and e-mails.

Enjoy!

CRI-O is now our default container runtime interface

We’re really excited to announce that as of today, we now officially supports the CRI-O Container Runtime Interface as our default way of interfacing with containers on your Kubic systems!

Um that’s great, but what is a Container Runtime Interface?

Contrary to what you might have heard, there are more ways to run containers than just the docker tool. In fact there are an increasing number of options, such as runc, rkt, frakti, cri-containerd and more. Most of these follow the OCI standard defining how the runtimes start and run your containers, but they lack a standard way of interfacing with an orchestrator. This makes things complicated for tools like kubernetes, which run on top of a container runtime to provide you with orchestration, high availability, and management.

Kubernetes therefore introduced a standard API to be able to talk to and manage a container runtime. This API is called the Container Runtime Interface (CRI).

Existing container runtimes like Docker use a “shim” to interface between Kubernetes and the runtime, but there is another way, using an interface that was designed to work with CRI natively. And that is where CRI-O comes into the picture.

Introduction to CRI-O

Started little over a year ago, CRI-O began as a Kubernetes incubator project, implementing the CRI Interface for OCI compliant runtimes. Using the lightweight runc runtime to actually run the containers, the simplest way of describing CRI-O would be as a lightweight alternative to the Docker engine, especially designed for running with Kubernetes.

As of 6th Sept 2018 CRI-O is no longer an incubator project, but now an official part of the Kubernetes family of tools.

Why CRI-O?

There are a lot of reasons the Kubic project love CRI-O, but to give a Top 4 some of the largest reasons include:

- A Truly Open Project: As already mentioned, CRI-O is operated as part of the broader Kubernetes community. There is a broad collection of contributors from companies including Red Hat, SUSE, Intel, Google, Alibaba, IBM and more. The project is run in a way that all these different stakeholders can actively propose changes and can expect to see them merged, or at least spur steps into that direction. This is harder to say of other similar projects.

-

Lightweight: CRI-O is made of lots of small components, each with specific roles, working together with other pieces to give you a fully functional container experience. In comparison, the Docker Engine is a heavyweight daemon which is communicated to using the

dockerCLI tool in a client/server fashion. You need to have the Daemon running before you can use the CLI, and if that daemon is dead, so is your ability to do anything with your containers. - More Securable: Every container run using the Docker CLI is a ‘child’ of that large Docker Daemon. This complicates or outright prevents the use of tooling like cgroups & security constraints to provide an extra layer of protection to your containers. As CRI-O containers are children of the process that spawned it (not the daemon) they’re fully compatible with these tools without complication. This is not only cool for Kubernetes, but also when using CRI-O with Podman, but more about that later…

- Aligned with Kubernetes: As an official Kubernetes project, CRI-O releases in lock step with Kubernetes, with similar version numbers. ie. CRI-O 1.11.x works with Kubernetes 1.11.x. This is hugely beneficial for a project like Kubic where we’re rolling and want to keep everything working together at the latest versions. On the other side of the fence, Kubernetes currently only officially supports Docker versions 17.03.x, now well over 1 year old and far behind the 18.06.x version we currently have in Kubic.

CRI-O and Kubernetes

Given one of the main roles of Kubic is to run Kubernetes, as of today, Kubic’s kubeadm system role is now designed to use CRI-O by default.

Our documentation has been updated to reflect the new CRI-O way of doing things.

The simplest way of describing it would be that we now have less steps than before.

You can now initialise your master node with a single command immediately after installation.

But you need to remember to add --cri-socket=/var/run/crio/crio.sock to your kubeadm init and join commands. (We’re looking into ways to streamline this).

CRI-O and MicroOS

Kubic is about more than Kubernetes, and our MicroOS system role is a perfect platform for running containers on stand-alone machines. That too now includes CRI-O as it’s default runtime interface.

In order to make use of CRI-O without Kubernetes, you need a command-line tool, and that tool is known as podman. It is now installed by default on Kubic MicroOS.

Podman

Podman has been available in Tumbleweed & Kubic for some time. Put simply, it is to CRI-O what the Docker CLI tool is to the Docker Engine daemon. It even has a very similar syntax.

- Use

podman runto run containers in the same way you’d expect fromdocker run -

podman pullpulls containers from registries, just likedocker pull, and by default ourpodmanis configured to use the same Docker Hub as many users would expect. - Some

podmancommands have additional functionality compared to theirdockerequivalents, such aspodman rm --allandpodman rmi --allwhich will remove all of your containers and their images respectively. - A full crib-sheet of podman commands and their docker equivalents is available

Podman also benefits from CRI-Os more lightweight architecture. Because every Podman container is a direct child of the podman command that created it, it’s trivial to use podman as part of systemd services. This be combined with systemd features like socket activation to do really cool things like starting your container only when users try to access it!

What about Docker?

As excited as we are about CRI-O and Podman, we’re not blind to the reality that many users just won’t care and will be more comfortable running the well known docker tool.

For the basic use case of running containers, both docker and podman can co-exist on a system safely. Therefore it will still be available and installed by default on Kubic MicroOS.

If you wish to remove it, just run transactional-update pkg rm -u docker-kubic and reboot.

The Docker Engine doesn’t co-exist with CRI-O quite so well in the Kubernetes scenario, so we do not install both by default on the kubeadm system role.

We still wish to support users wishing to use the Docker Engine with Kubernetes. Therefore to swap from CRI-O to the Docker Engine just run transactional-update pkg in patterns-caasp-alt-container-runtime -cri-o-kubeadm-criconfig and reboot.

Alternatively if you’re installing Kubic from the installation media you can deselect the “Container Runtime” and instead choose the “Alternative Container Runtime” pattern from the “Software” option as part of the installation.

Regardless of which runtime you choose to use, thanks for using Kubic and please join in, send us your feedback, code, and other contributions, and remember, have a lot of fun!.

Learning from Pain

Pain is something we generally try to avoid; pain is unpleasant, but it also serves an important purpose.

Acute pain can be feedback that we need to avoid doing something harmful to our body, or protect something while it heals. Pain helps us remember the cause of injuries and adapt our behaviour to avoid a repeat.

As a cyclist I occasionally get joint pain that indicates I need to adjust my riding position. If I just took painkillers and ignored the pain I’d permanently injure myself over time.

I’m currently recovering from a fracture after an abrupt encounter with a pothole. The pain is helping me rest and allow time for the healing process. The memory of the pain will also encourage me to consider the risk of potholes when riding with poor visibility in the future.

We have similar feedback mechanisms when planning, building, and running software; we often find things painful.

Alas, rather than learn from pain and let it guide us, we all too often stock up on painkillers in the form of tooling or practices that let us press on obstinately doing the same thing that caused the pain in the first place.

Here are some examples…

Painful Tests

Automated tests can be a fantastic source of feedback that helps us improve our software and learn to write better software in the future. Tests that are hard to write are a sign something could be better.

The tests only help us if we listen to the pain we feel when tests are hard to write and read. If we reach for increasingly sophisticated tooling to allow us to continue doing the painful things, then we won’t realise the benefits. Or worse, if we avoid unit testing in favour of higher level tests, we’ll miss out on this valuable feedback altogether.

Here’s an example of a test that was painful to write and read, testing the sending of a booking confirmation email.

- The test method is very long at around 50 lines of code

- We have boilerplate setting up stubbing for things irrelevant to the test such as queue sizes and supervisors

- We’ve got flakiness from assuming the current date will be the same in two places—the test might not pass if run at midnight, or when changing the time

- There’s multiple assertions for multiple responsibilities

- We’ve had to work hard to capture side effects

Feeling this pain, one response would be to reach for painkillers in the form of more powerful mocking tools. If we do so we end up with something like this. Note that we haven’t improved the implementation at all (it’s unchanged), but now we’re feeling a lot less pain from the test.

- The test method is a quarter the length—-but the implementation is as complex

- The flakiness is gone as the date is mocked to a constant value—but the implementation still has a hard dependency on the system time.

- We’re no longer forced to stub irrelevant detail—but the implementation still has dependencies on collaborators with too many responsibilities.

- We only have a single assertion—but there are still as many responsibilities in the implementation

- It’s easier to capture the side effects—but they’re still there

A better response would be to reflect on the underlying causes of the pain. Here’s one direction we could go that removes much of the pain and doesn’t need complex frameworks

- The test method is shorter, and the implementation does less

- The flakiness is gone as the implementation no longer has a hard dependency on the system time

- We’re no longer forced to stub irrelevant detail because the implementation only depends on what it needs

- We only have a single assertion, because we’ve reduced the scope of the implementation to merely composing the email. We’ve factored out the responsibility of sending the email.

- We’ve factored out the side effects so we can test them separately

My point is not that the third example is perfect (it’s quickly thrown together), nor am I arguing that mocking frameworks are bad. My point is that by learning from the pain (rather than rushing to hide it with tooling before we’ve learnt anything) we can end up with something better.

The pain we feel when writing tests can also be a prompt to reflect on our development process—do we spend enough time refactoring when writing the tests, or do we move onto the next thing as soon as they go green? Are we working in excessively large steps that let us get into messes like the above that are painful to clean up?

n.b. there’s lots of better examples of learning from test feedback in chapter 20 of the GOOS book.

Painful Dependency Injection

Dependency injection seems to have become synonymous with frameworks like spring, guice, dagger; as opposed to the relatively simple idea of “passing stuff in”. Often people reach for dependency injection frameworks out of habit, but sometimes they’re used as a way of avoiding design feedback.

If you start building a trivial application from scratch you’ll likely not feel the need for a dependency injection framework at the outset. You can wire up your few dependencies yourself, passing them to constructors or function calls.

As complexity increases this can become unwieldy, tedious, even painful. It’s easy to reach for a dependency injection framework to magically wire all your dependencies together to remove that boilerplate.

However, doing so prematurely can deprive you of the opportunity to listen to the design feedback that this pain is communicating.

Could you reduce the wiring pain through increased modularity—adding, removing, or finding better abstractions?

Does the wiring code have more detail than you’d include in a document explaining how it works? How can you align the code with how you’d naturally explain it? Is the wiring code understandable to a domain expert? How can you make it more so?

Here’s a little example of some manual wiring of dependencies. While short, it’s quite painful:

- There’s a lot of components to wire together

- There’s a mixture of domain concepts and details like database choices

- The ordering is difficult to get right to resolve dependencies, and it obscures intent

At this point we could reach for a DI framework and @Autowire or @Inject these dependencies and the wiring pain would disappear almost completely.

However, if instead we listen to the pain, we can spot some opportunities to improve the design. Here’s an example of one direction we could go

- We’ve spotted and fixed the dashboard’s direct dependency on the probe executor, it now uses the status reporter like the pager.

- The dashboard and pager shared a lot of wiring as they had a common purpose in providing visibility on the status of probes. There was a missing concept here, adding it has simplified the wiring considerably.

- We’ve separated the wiring of the probe executor from the rest.

After applying these refactorings the top level wiring reads more like a description of our intent.

Clearly this is just a toy example, and the refactoring is far from complete, but I hope it illustrates the point: dependency injection frameworks are useful, but be aware of the valuable design feedback they may be hiding from you.

Painful Integration

It’s common to experience “merge pain” when trying to integrate long lived branches of code and big changesets to create a releasable build. Sometimes the large changesets don’t even pass tests, sometimes your changes conflict with changes others on the team have made.

One response to this pain is to reach for increasingly sophisticated build infrastructure to hide some of the pain. Infrastructure that continually runs tests against branched code, or continually checks merges between branches can alert you to problems early. Sadly, by making the pain more bearable, we risk depriving ourselves of valuable feedback.

Ironically continuous-integration tooling often seems to be used to reduce the pain felt when working on large, long lived changesets; a practice I like to call “continuous isolation”.

You can’t automate away the human feedback available when integrating your changes with the rest of the team—without continuous integration you miss out on others noticing that they’re working in the same area, or spotting problems with your approach early.

You also can’t replace the production feedback possible from integrating small changes all the way to production (or a canary deployment) frequently.

Sophisticated build infrastructure can give you the illusion of safety by hiding the pain from your un-integrated code. By continuing to work in isolation you risk more substantial pain later when you integrate and deploy your larger, riskier changeset. You’ll have a higher risk of breaking production, a higher risk of merge conflicts, as well as a higher risk of feedback from colleagues being late, and thus requiring substantial re-work.

Painful Alerting

Over-alerting is a serious problem; paging people spuriously for non-existent problems or issues that do not require immediate attention undermines confidence, just like flaky test suites.

It’s easy to respond to overalerting by paying less and less attention to production alerts until they are all but ignored. Learning to ignore the pain rather than listening to its feedback.

Another popular reaction is to desire increasingly sophisticated tooling to handle the flakiness—from flap detection algorithms, to machine learning, to people doing triage. These often work for a while—tools can assuage some of the pain, but they don’t address the underlying causes.

The situation won’t significantly improve without a feedback mechanism in place, where you improve both your production infrastructure and approach to alerting based on reality.

The only effective strategy for reducing alerting noise that I’ve seen is: every alert results in somebody taking action to remediate it and stop it happening again—even if that action is to delete the offending alerting rule or amend it. Analyse the factors that resulted in the alert firing, and make a change to improve the reliability of the system.

Yes, this sometimes does mean more sophisticated tooling when it’s not possible to prevent the alert firing in similar spurious circumstances with the tooling available.

However it also means considering the alerts themselves. Did the alert go off because there was an impact to users, the business, or a threat to our error budget that we consider unacceptable? If not, how can we make it more reliable or relevant?

Are we alerting on symptoms and causes rather than things that people actually care about?

Who cares about a server dying if no users are affected? Who cares about a traffic spike if our systems handle it with ease?

We can also consider the reliability of the production system itself. Was the alert legitimate? Maybe our production system isn’t reliable enough to run (without constant human supervision) at the level of service we desire? If improving the sophistication of our monitoring is challenging, maybe we can make the system being monitored simpler instead?

Getting alerted or paged is painful, particularly if it’s in the middle of the night. It’ll only get less painful long-term if you address the factors causing the pain rather than trying hard to ignore it.

Painful Deployments

If you’ve been developing software for a while you can probably regale us with tales of breaking production. These anecdotes are usually entertaining, and people enjoy telling them once enough time has passed that it’s not painful to re-live the situation. It’s fantastic to learn from other people’s painful experiences without having to live through them ourselves.

It’s often painful when you personally make a change and it results in a production problem, at least at the time—not something you want to repeat.

Making a change to a production system is a risky activity. It’s easy to associate the pain felt when something goes wrong, with the activity of deploying to production, and seek to avoid the risk by deploying less frequently.

It’s also common to indulge in risk-management theatre: adding rules, processes, signoff and other bureaucracy—either because we mistakenly believe it reduces the risk, or because it helps us look better to stakeholders or customers. If there’s someone else to blame when things go wrong, the pain feels less acute.

Unfortunately, deploying less frequently results in bigger changes that we understand less well; inadvertently increasing risk in the long run.

Risk-management theatre can even threaten the ability of the organisation to respond quickly to the kind of unavoidable incidents it seeks to protect against.

Yes, most production issues are caused by an intentional change made to the system, but not all are. Production issues get caused by leap second bugs, changes in user behaviour, spikes in traffic, hardware failures and more. Being able to rapidly respond to these issues and make changes to production systems at short notice reduces the impact of such incidents.

Responding to the pain of deployments that break production by changing production less often, is pain avoidance rather than addressing the cause.

Deploying to production is like bike maintenance. If you do it infrequently it’s a difficult job each time and you’re liable to break something. Components seize together, the procedures are unfamiliar, and if you don’t test-ride it when you’re done then it’s unlikely to work when you want to ride. If this pain leads you to postpone maintenance, then you increase the risk of an accident from a worn chain or ineffective brakes.

A better response with both bikes and production systems is to keep them in good working order through regular, small, safe changes.

With production software changes we should think about how we can make it a safe and boring activity—-how can we reduce the risk of deploying changes to production, or how can we reduce the impact of deploying bad changes to production.

Could the production failure have been prevented through better tests?

Would the problem have been less severe if our production monitoring had caught it sooner?

Might we have spotted the problem ourselves if we had a culture of testing in production and were actually checking that our stuff worked once in production?

Perhaps canary deploys would reduce the risk of a business-impacting breakage?

Would blue-green deployments reduce the risk by enabling swift recovery?

Can we improve our architecture to reduce the risk of data damage from bad deployments?

There are many many ways to reduce the risk of deployments, we can channel the pain of bad deployments into improvements to our working practices, tooling, and architecture.

Painful Change

After spending days or weeks building a new product or feature, it’s quite painful to finally demo it to the person who asked for it and discover that it’s no longer what they want. It’s also painful to release a change into production and discover it doesn’t achieve the desired result, maybe no-one uses it, or it’s not resulting in an uptick to your KPI.

It’s tempting to react to this by trying to nail down requirements first before we build. If we agree exactly what we’re building up front and nail down the acceptance criteria then we’ll eliminate the pain, won’t we?

Doing so may reduce our own personal pain—we can feel satisfied that we’ve consistently delivered what was asked of us. Unfortunately, reducing our own pain has not reduced the damage to our organisation. We’re still wasting time and money by building valueless things. Moreover, we’re liable to waste even more of our time now that we’re not feeling the pain.

Again, we need to listen to what the pain’s telling us; what are the underlying factors that are leading to us building the wrong things?

Fundamentally, we’re never going to have perfect knowledge about what to build, unless we’re building low value things that have been built many times before. So instead let’s try to create an environment where it’s safe to be wrong in small ways. Let’s listen to the feedback from small pain signals that encourage us to adapt, and act on it, rather than building up a big risky bet that could result in a serious injury to the organisation if we’re wrong.

If we’re frequently finding we’re building the wrong things, maybe there are things we can change about how we work, to see if it reduces the pain.

Do we need to understand the domain better? We could spend time with domain experts, and explore the domain using a cheaper mechanism than software development, such as eventstorming.

Perhaps we’re not having frequent and quality discussions with our stakeholders? Sometimes minutes of conversation can save weeks of coding.

Are we not close enough to our customers or users? Could we increase empathy using personas, or attending sales meetings, or getting out of the building and doing some user testing?

Perhaps having a mechanism to experiment and test our hypotheses in production cheaply would help?

Are there are lighter-weight ways we can learn that don’t involve building software? Could we try selling the capabilities optimistically, or get feedback from paper prototypes, or could we hack together a UI facade and put it in front of some real users?

We can listen to the pain we feel when we’ve built something that doesn’t deliver value, and feed it into improving not just the product, but also our working practices and habits. Let’s make it more likely that we’ll build things of value in the future.

Acute Pain

Many people do not have the privilege of living pain-free most of the time, sadly we have imperfect bodies and many live with chronic pain. Acute pain, however, can be a useful feedback mechanism.

When we find experiences and day to day work painful, it’s often helpful to think about what’s causing that pain and, what we can do to eliminate the underlying causes, before we reach for tools and processes to work around or hide the pain.

Listening to small amounts of acute pain, looking for the cause and taking action sets up feedback loops that help us improve over time; ignoring the pain leads to escalating risks that build until something far more painful happens.

What examples do you have of people treating the pain rather than the underlying causes?

The post Learning from Pain appeared first on Benji's Blog.

Nextcloud 14 and Video Verification

Today the Nextcloud community released Nextcloud 14. This release comes with a ton of improvements in the areas of User Experience, Accessibility, Speed, GDPR compliance, 2 Factor Authentication, Collaboration, Security and many other things. You can find an overview here

But there is one feature I want to highlight because I find it especially noteworthy and interesting. Some people ask us why we are doing more than the classic file sync and share. Why do we care about Calendar, Contacts, Email, Notes, RSS Reader, Deck, Chat, Video and audio calls and so on.

It all fits together

The reason is that I believe that a lot if these features belong together. There is a huge benefit in an integrated solution. This doesn’t mean that everyone needs and wants all features. This is why we make it possible to switch all of them off so that you and your users have only the functionality available that you really want. But there are huge advantages to have deep integration. This is very similar to the way KDE and GNOME integrate all applications together on the Desktop. Or how Office 365 and Google Suite integrate cloud applications.

The why of Video Verification

The example I want to talk about for this release is Video Verification. It is a solution for a problem that was unsolved until now.

Let’s imagine you have a very confidential document that you want to share with one specific person and only this person. This can be important for lawyers, doctors or bank advisors. You can send the sharing link to the email you might have of this person but you can’t be sure that it reaches this person and only exactly this person. You don’t know if the email is seen by the mailserver admin or the kid who plays with the smartphone or the spouse or the hacker who has hijacked the PC or the mail account of the recipient. The document is transmitted vie encrypted https of course but you don’t know who is on the other side. Even if you sent the password via another channel, you can’t have 100% certainty.

Let’s see how this is done in other cases.

TLS solves two problems for https. The data transfer is encrypted with strong encryption algorithms but this is not enough. Additionally certificates are used to make sure that you are actually talking to the right endpoint on the other side of the https connection. It doesn’t help to securily communicate with what you think is your bank but is actually an attacker!

In GPG encrypted emails the encryption is done with strong and proven algorithms. But there is an additional key signing needed to make sure that the key is owned by the right person.

This second part, the verification of the identity of the recipient, is missing in file sync and share until now. Video verification solves that.

How it works

I want to share a confidential document with someone. In the Nextcloud sharing dialog I type in the email of the person and i activate the option ‘Password via Talk’ then I can set a password to protect the document.

The recipient gets a link to the document by email. Once the person clicks on the link the person sees a screen that asks for a password. The person can click on the ‘request password’ button and then a sidebar open which initiates a Nextcloud Talk call to me. I get a notification about this call in my web interface, via my Nextcloud Desktop client or, most likely to get my attention, my phone will ring because the Nextcloud app on my phone got a push notification. I answer my phone and I have an end to end encrypted, peer to peer video call with the recipient of the link. I can verify that this is indeed the right person. Maybe because I know the person or because the person holds up a personal picture ID. Once I’m sure it is the right person I tell the person the password to the document. The person types in the password and has access to the document.

This procedure is of course over the top for normal standard shares. But if you are dealing with very confidential documents because you are a doctor, a lawyer, a bank or a whistleblower then this is the only way to make sure that the document reaches the right person.

I’m happy and a b it proud that the Nextcloud community is able to produce such innovative features that don’t even exist in proprietary solution

As always all the server software, the mobile apps and the desktop clients are 100% open source, free software and can be self hosted by everyone. Nextcloud is a fully open source community driven project without a contributor agreement or closed source and proprietary extensions or an enterprise edition.

You can get more information on nextcloud.com or contribute at github.com/nextcloud

PHP FPM Apparmor

I haven’t been using apache for a few years now … oh wow maybe like 15 years now.

There was one feature I really liked with apache and apparmor though … mod_changehat.

The module allows me to assign different apparmor scopes to apache scopes. So

you could limit that your wordpress vhost can not access the files of your

nextcloud vhost even though they are running in the same apache.

My gdk-pixbuf braindump

I want to write a braindump on the stuff that I remember from gdk-pixbuf's history. There is some talk about replacing it with something newer; hopefully this history will show some things that worked, some that didn't, and why.

The beginnings

Gdk-pixbuf started as a replacement for Imlib, the image loading and rendering library that GNOME used in its earliest versions. Imlib came from the Enlightenment project; it provided an easy API around the idiosyncratic libungif, libjpeg, libpng, etc., and it maintained decoded images in memory with a uniform representation. Imlib also worked as an image cache for the Enlightenment window manager, which made memory management very inconvenient for GNOME.

Imlib worked well as a "just load me an image" library. It showed that a small, uniform API to load various image formats into a common representation was desirable. And in those days, hiding all the complexities of displaying images in X was very important indeed.

The initial API

Gdk-pixbuf replaced Imlib, and added two important features: reference counting for image data, and support for an alpha channel.

Gdk-pixbuf appeared with support for RGB(A) images. And although in

theory it was possible to grow the API to support other

representations, GdkColorspace never acquired anything other than

GDK_COLORSPACE_RGB, and the bits_per_sample argument to some

functions only ever supported being 8. The presence or absence of an alpha

channel was done with a gboolean argument in conjunction with that

single GDK_COLORSPACE_RGB value; we didn't have something like

cairo_format_t which actually specifies the pixel format in single

enum values.

While all the code in gdk-pixbuf carefully checks that those conditions are met — RGBA at 8 bits per channel —, some applications inadvertently assume that that is the only possible case, and would get into trouble really fast if gdk-pixbuf ever started returning pixbufs with different color spaces or depths.

One can still see the battle between bilevel-alpha vs. continuous-alpha in this enum:

typedef enum

{

GDK_PIXBUF_ALPHA_BILEVEL,

GDK_PIXBUF_ALPHA_FULL

} GdkPixbufAlphaMode;

Fortunately, only the "render this pixbuf with alpha to an Xlib drawable" functions take values of this type: before the Xrender days, it was a Big Deal to draw an image with alpha to an X window, and applications often opted to use a bitmask instead, even if they had jagged edges as a result.

Pixel formats

The only pixel format that ever got implemented was unpremultiplied RGBA on all platforms. Back then I didn't understand premultiplied alpha! Also, the GIMP followed that scheme, and copying it seemed like the easiest thing.

After gdk-pixbuf, libart also copied that pixel format, I think.

But later we got Cairo, Pixman, and all the Xrender stack. These prefer premultiplied ARGB. Moreover, Cairo prefers it if each pixel is actually a 32-bit value, with the ARGB values inside it in platform-endian order. So if you look at a memory dump, a Cairo pixel looks like BGRA on a little-endian box, while it looks like ARGB on a big-endian box.

Every time we paint a GdkPixbuf to a cairo_t, there is a

conversion from unpremultiplied RGBA to premultiplied, platform-endian

ARGB. I talked a bit about this in Reducing the number of image

copies in GNOME.

The loading API

The public loading API in gdk-pixbuf, and its relationship to loader plug-ins, evolved in interesting ways.

At first the public API and loaders only implemented load_from_file:

you gave the library a FILE * and it gave you back a GdkPixbuf.

Back then we didn't have a robust MIME sniffing framework in the form

of a library, so gdk-pixbuf got its own. This lives in the

mostly-obsolete GdkPixbufFormat machinery; it

even has its own little language for sniffing file headers!

Nowadays we do most MIME sniffing with GIO.

After the intial load_from_file API... I think we got progressive

loading first, and animation support aftewards.

Progressive loading

This where the calling program feeds chunks of bytes to the library,

and at the end a fully-formed GdkPixbuf comes out, instead of having

a single "read a whole file" operation.

We conflated this with a way to get updates on how the image area gets modified as the data gets parsed. I think we wanted to support the case of a web browser, which downloads images slowly over the network, and gradually displays them as they are downloaded. In 1998, images downloading slowly over the network was a real concern!

It took a lot of very careful work to convert the image loaders, which parsed a whole file at a time, into loaders that could maintain some state between each time that they got handed an extra bit of buffer.

It also sounded easy to implement the progressive updating API by simply emitting a signal that said, "this rectangular area got updated from the last read". It could handle the case of reading whole scanlines, or a few pixels, or even area-based updates for progressive JPEGs and PNGs.

The internal API for the image format loaders still keeps a

distinction between the "load a whole file" API and the "load an image

in chunks". Not all loaders got redone to simply just use the second

one: io-jpeg.c still implements loading whole files by calling the

corresponding libjpeg functions. I think it could remove that code

and use the progressive loading functions instead.

Animations

Animations: we followed the GIF model for animations, in which each frame overlays the previous one, and there's a delay set between each frame. This is not a video file; it's a hacky flipbook.

However, animations presented the problem that the whole gdk-pixbuf API was meant for static images, and now we needed to support multi-frame images as well.

We defined the "correct" way to use the gdk-pixbuf library as to

actually try to load an animation, and then see if it is a

single-frame image, in which case you can just get a GdkPixbuf for

the only frame and use it.

Or, if you got an animation, that would be a GdkPixbufAnimation

object, from which you could ask for an iterator to get each frame as

a separate GdkPixbuf.

However, the progressive updating API never got extended to really

support animations. So, we have awkward functions like

gdk_pixbuf_animation_iter_on_currently_loading_frame() instead.

Necessary accretion

Gdk-pixbuf got support for saving just a few formats: JPEG, PNG, TIFF, ICO, and some of the formats that are implemented with the Windows-native loaders.

Over time gdk-pixbuf got support for preserving some metadata-ish chunks from formats that provide it: DPI, color profiles, image comments, hotspots for cursors/icons...

While an image is being loaded with the progressive loaders, there is a clunky way to specify that one doesn't want the actual size of the image, but another size instead. The loader can handle that situation itself, hopefully if an image format actually embeds different sizes in it. Or if not, the main loading code will rescale the full loaded image into the size specified by the application.

Historical cruft

GdkPixdata - a way to embed binary image data in executables, with a

funky encoding. Nowadays it's just easier to directly store a PNG or

JPEG or whatever in a GResource.

contrib/gdk-pixbuf-xlib - to deal with old-style X drawables.

Hopefully mostly unused now, but there's a good number of mostly old,

third-party software that still uses gdk-pixbuf as an image loader and

renderer to X drawables.

gdk-pixbuf-transform.h - Gdk-pixbuf had some very high-quality

scaling functions, which the original versions of EOG used for the

core of the image viewer. Nowadays Cairo is the preferred way of

doing this, since it not only does scaling, but general affine

transformations as well. Did you know that

gdk_pixbuf_composite_color takes 17 arguments, and it can composite

an image with alpha on top of a checkerboard? Yes, that used to be

the core of EOG.

Debatable historical cruft

gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels(). This lets the program look into the actual

pixels of a loaded pixbuf, and modify them. Gdk-pixbuf just did not

have a concept of immutability.

Back in GNOME 1.x / 2.x, when it was fashionable to put icons beside menu items, or in toolbar buttons, applications would load their icon images, and modify them in various ways before setting them onto the corresponding widgets. Some things they did: load a colorful icon, desaturate it for "insensitive" command buttons or menu items, or simulate desaturation by compositing a 1x1-pixel checkerboard on the icon image. Or lighten the icon and set it as the "prelight" one onto widgets.

The concept of "decode an image and just give me the pixels" is of course useful. Image viewers, image processing programs, and all those, of course need this functionality.

However, these days GTK would prefer to have a way to decode an image, and ship it as fast as possible ot the GPU, without intermediaries. There is all sorts of awkward machinery in the GTK widgets that can consume either an icon from an icon theme, or a user-supplied image, or one of the various schemes for providing icons that GTK has acquired over the years.

It is interesting to note that gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels() was available

pretty much since the beginning, but it was only until much later that

we got gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels_with_length(), the "give me the guchar

* buffer and also its length" function, so that calling code has a

chance of actually checking for buffer overruns. (... and it is one

of the broken "give me a length" functions that returns a guint

rather than a gsize. There is a better

gdk_pixbuf_get_byte_length() which actually returns a gsize,

though.)

Problems with mutable pixbufs

The main problem is that as things are right now, we have no flexibility in changing the internal representation of image data to make it better for current idioms: GPU-specific pixel formats may not be unpremultiplied RGBA data.

We have no API to say, "this pixbuf has been modified", akin to

cairo_surface_mark_dirty(): once an application calls

gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels(), gdk-pixbuf or GTK have to assume that the

data will be changed and they have to re-run the pipeline to send

the image to the GPU (format conversions? caching? creating a

texture?).

Also, ever since the beginnings of the gdk-pixbuf API, we had a way to

create pixbufs from arbitrary user-supplied RGBA buffers: the

gdk_pixbuf_new_from_data functions. One problem with this scheme is

that memory management of the buffer is up to the calling application,

so the resulting pixbuf isn't free to handle those resources as it

pleases.

A relatively recent addition is gdk_pixbuf_new_from_bytes(), which

takes a GBytes buffer instead of a random guchar *. When a pixbuf

is created that way, it is assumed to be immutable, since a GBytes

is basically a shared reference into a byte buffer, and it's just

easier to think of it as immutable. (Nothing in C actually enforces

immutability, but the API indicates that convention.)

Internally, GdkPixbuf actually prefers to be created from a

GBytes. It will downgrade itself to a guchar * buffer if

something calls the old gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels(); in the best case,

that will just take ownership of the internal buffer from the

GBytes (if the GBytes has a single reference count); in the worst

case, it will copy the buffer from the GBytes and retain ownership

of that copy. In either case, when the pixbuf downgrades itself to

pixels, it is assumed that the calling application will modify the

pixel data.

What would immutable pixbufs look like?

I mentioned this a bit in "Reducing Copies". The loaders in gdk-pixbuf would create immutable pixbufs, with an internal representation that is friendly to GPUs. In the proposed scheme, that internal representation would be a Cairo image surface; it can be something else if GTK/GDK eventually prefer a different way of shipping image data into the toolkit.

Those pixbufs would be immutable. In true C fashion we can call it

undefined behavior to change the pixel data (say, an app could request

gimme_the_cairo_surface and tweak it, but that would not be

supported).

I think we could also have a "just give me the pixels" API, and a

"create a pixbuf from these pixels" one, but those would be one-time

conversions at the edge of the API. Internally, the pixel data that

actually lives inside a GdkPixbuf would remain immutable, in some

preferred representation, which is not necessarily what the

application sees.

What worked well

A small API to load multiple image formats, and paint the images easily to the screen, while handling most of the X awkwardness semi-automatically, was very useful!

A way to get and modify pixel data: applications clearly like doing this. We can formalize it as an application-side thing only, and keep the internal representation immutable and in a format that can evolve according to the needs of the internal API.

Pluggable loaders, up to a point. Gdk-pixbuf doesn't support all the image formats in the world out of the box, but it is relatively easy for third-parties to provide loaders that, once installed, are automatically usable for all applications.

What didn't work well

Having effectively two pixel formats supported, and nothing else: gdk-pixbuf does packed RGB and unpremultiplied RGBA, and that's it. This isn't completely terrible: applications which really want to know about indexed or grayscale images, or high bit-depth ones, are probably specialized enough that they can afford to have their own custom loaders with all the functionality they need.

Pluggable loaders, up to a point. While it is relatively easy to create third-party loaders, installation is awkward from a system's perspective: one has to run the script to regenerate the loader cache, there are more shared libraries running around, and the loaders are not sandboxed by default.

I'm not sure if it's worthwhile to let any application read "any" image format if gdk-pixbuf supports it. If your word processor lets you paste an image into the document... do you want it to use gdk-pixbuf's limited view of things and include a high bit-depth image with its probably inadequate conversions? Or would you rather do some processing by hand to ensure that the image looks as good as it can, in the format that your word processor actually supports? I don't know.

The API for animations is very awkward. We don't even support APNG... but honestly I don't recall actually seeing one of those in the wild.

The progressive loading API is awkward. The "feed some bytes into the loader" part is mostly okay; the "notify me about changes to the pixel data" is questionable nowadays. Web browsers don't use it; they implement their own loaders. Even EOG doesn't use it.

I think most code that actually connects to GdkPixbufLoader's

signals only uses the size-prepared signal — the one that gets

emitted soon after reading the image headers, when the loader gets to

know the dimensions of the image. Apps sometimes use this to say,

"this image is W*H pixels in size", but don't actually decode the

rest of the image.

The gdk-pixbuf model of static images, or GIF animations, doesn't work well for multi-page TIFFs. I'm not sure if this is actualy a problem. Again, applications with actual needs for multi-page TIFFs are probably specialized enough that they will want a full-featured TIFF loader of their own.

Awkward architectures

Thumbnailers

The thumbnailing system has slowly been moving towards a model where we actually have thumbnailers specific to each file format, instead of just assuming that we can dump any image into a gdk-pixbuf loader.

If we take this all the way, we would be able to remove some weird code in, for example, the JPEG pixbuf loader. Right now it supports loading images at a size that the calling code requests, not only at the "natural" size of the JPEG. The thumbnailer can say, "I want to load this JPEG at 128x128 pixels" or whatever, and in theory the JPEG loader will do the minimal amount of work required to do that. It's not 100% clear to me if this is actually working as intended, or if we downscale the whole image anyway.

We had a distinction between in-process and out-of-process thumbnailers, and it had to do with the way pixbuf loaders are used; I'm not sure if they are all out-of-process and sandboxed now.

Non-raster data

There is a gdk-pixbuf loader for SVG images which uses librsvg

internally, but only in a very basic way: it simply loads the SVG at

its preferred size. Librsvg jumps through some hoops to compute a

"preferred size" for SVGs, as not all of them actually indicate one.

The SVG model would rather have the renderer say that the SVG is to be

inserted into a rectangle of certain width/height, and

scaled/positioned inside the rectangle according to some other

parameters (i.e. like one would put it inside an HTML document, with a

preserveAspectRatio attribute and all that). GNOME applications

historically operated with a different model, one of "load me an

image, I'll scale it to whatever size, and paint it".

This gdk-pixbuf loader for SVG files gets used for the SVG thumbnailer, or more accurately, the "throw random images into a gdk-pixbuf loader" thumbnailer. It may be better/cleaner to have a specific thumbnailer for SVGs instead.

Even EOG, our by-default image viewer, doesn't use the gdk-pixbuf loader for SVGs: it actually special-cases them and uses librsvg directly, to be able to load an SVG once and re-render it at different sizes if one changes the zoom factor, for example.

GTK reads its SVG icons... without using librsvg... by assuming that

librsvg installed its gdk-pixbuf loader, so it loads them as any

normal raster image. This kind of dirty, but I can't quite pinpoint

why. I'm sure it would be convenient for icon themes to ship a single

SVG with tons of icons, and some metadata on their ids, so that GTK

could pick them out of the SVG file with rsvg_render_cairo_sub() or

something. Right now icon theme authors are responsible for splitting

out those huge SVGs into many little ones, one for each icon, and I

don't think that's their favorite thing in the world to do :)

Exotic raster data

High bit-depth images... would you expect EOG to be able to load them? Certainly; maybe not with all the fancy conversions from a real RAW photo editor. But maybe this can be done as EOG-specific plugins, rather than as low in the platform as the gdk-pixbuf loaders?

(Same thing for thumbnailing high bit-depth images: the loading code should just provide its own thumbnailer program for those.)

Non-image metadata

The gdk_pixbuf_set_option / gdk_pixbuf_get_option family of

functions is so that pixbuf loaders can set key/value pairs of strings

onto a pixbuf. Loaders use this for comment blocks, or ICC profiles

for color calibration, or DPI information for images that have it, or

EXIF data from photos. It is up to applications to actually use this

information.

It's a bit uncomfortable that gdk-pixbuf makes no promises about the

kind of raster data it gives to the caller: right now it is raw

RGB(A) data that is not gamma-corrected nor in any particular color

space. It is up to the caller to see if the pixbuf has an ICC profile

attached to it as an option. Effectively, this means that

applications don't know if they are getting SRGB, or linear RGB, or

what... unless they specifically care to look.

The gdk-pixbuf API could probably make promises: if you call this function you will get SRGB data; if you call this other function, you'll get the raw RGBA data and we'll tell you its colorspace/gamma/etc.

The various set_option / get_option pairs are also usable by the

gdk-pixbuf saving code (up to now we have just talked about

loaders). I don't know enough about how applications use the saving

code in gdk-pixbuf... the thumbnailers use it to save PNGs or JPEGs,

but other apps? No idea.

What I would like to see

Immutable pixbufs in a useful format. I've started work on

this in a merge request; the internal code is now ready

to take in different internal representations of pixel data. My goal

is to make Cairo image surfaces the preferred, immutable, internal

representation. This would give us a

gdk_pixbuf_get_cairo_surface(), which pretty much everything that

needs one reimplements by hand.

Find places that assume mutable pixbufs. To gradually deprecate

mutable pixbufs, I think we would need to audit applications and

libraries to find places that cause GdkPixbuf structures to degrade

into mutable ones: basically, find callers of

gdk_pixbuf_get_pixels() and related functions, see what they do, and

reimplement them differently. Maybe they don't need to tint icons by

hand anymore? Maybe they don't need icons anymore, given our

changing UI paradigms? Maybe they are using gdk-pixbuf as an image

loader only?

Reconsider the loading-updates API. Do we need the

GdkPixbufLoader::area-updated signal at all? Does anything break

if we just... not emit it, or just emit it once at the end of the

loading process? (Caveat: keeping it unchanged more or less means

that "immutable pixbufs" as loaded by gdk-pixbuf actually mutate while

being loaded, and this mutation is exposed to applications.)

Sandboxed loaders. While these days gdk-pixbuf loaders prefer the progressive feed-it-bytes API, sandboxed loaders would maybe prefer a read-a-whole-file approach. I don't know enough about memfd or how sandboxes pass data around to know how either would work.

Move loaders to Rust. Yes, really. Loaders are

security-sensitive, and while we do need to sandbox them, it would

certainly be better to do them in a memory-safe language. There are

already pure Rust-based image loaders: JPEG,

PNG, TIFF, GIF, ICO.

I have no idea how featureful they are. We can certainly try them

with gdk-pixbuf's own suite of test images. We can modify them to add

hooks for things like a size-prepared notification, if they don't

already have a way to read "just the image headers".

Rust makes it very easy to plug in micro-benchmarks, fuzz testing, and other modern amenities. These would be perfect for improving the loaders.

I started sketching a Rust backend for gdk-pixbuf

loaders some months ago, but there's nothing useful

yet. One mismatch between gdk-pixbuf's model for loaders, and the

existing Rust codecs, is that Rust codecs generally take something

that implements the Read trait: a blocking API to read bytes from

abstract sources; it's a pull API. The gdk-pixbuf model is a push

API: the calling code creates a loader object, and then pushes bytes

into it. The gdk-pixbuf convenience functions that take a

GInputStream basically do this:

loader = gdk_pixbuf_loader_new (...);

while (more_bytes) {

n_read = g_input_stream_read (stream, buffer, ...);

gdk_pixbuf_loader_write(loader, buffer, n_read, ...);

}

gdk_pixbuf_loader_close (loader);

However, this cannot be flipped around easily. We could probably use a second thread (easy, safe to do in Rust) to make the reader/decoder thread block while the main thread pushes bytes into it.

Also, I don't know how the Rust bindings for GIO present things like

GInputStream and friends, with our nice async cancellables and all

that.

Deprecate animations? Move that code to EOG, just so one can look at memes in it? Do any "real apps" actually use GIF animations for their UI?

Formalize promises around returned color profiles, gamma, etc. As mentioned above: have an "easy API" that returns SRGB, and a "raw API" that returns the ARGB data from the image, plus info on its ICC profile, gamma, or any other info needed to turn this into a "good enough to be universal" representation. (I think all the Apple APIs that pass colors around do so with an ICC profile attached, which seems... pretty much necessary for correctness.)

Remove the internal MIME-sniffing machinery. And just use GIO's.

Deprecate the crufty/old APIs in gdk-pixbuf.

Scaling/transformation, compositing, GdkPixdata,

gdk-pixbuf-csource, all those. Pixel crunching can be done by

Cairo; the others are better done with GResource these days.

Figure out if we want blessed codecs; fix thumbnailers. Link those loaders statically, unconditionally. Exotic formats can go in their own custom thumbnailers. Figure out if we want sandboxed loaders for everything, or just for user-side images (not ones read from the trusted system installation).

Have GTK4 communicate clearly about its drawing model. I think we are having a disconnect between the GUI chrome, which is CSS/GPU friendly, and graphical content generated by applications, which by default right now is done via Cairo. And having Cairo as a to-screen and to-printer API is certainly very convenient! You Wouldn't Print a GUI, but certainly you would print a displayed document.

It would also be useful for GTK4 to actually define what its preferred image format is if it wants to ship it to the GPU with as little work as possible. Maybe it's a Cairo image surface? Maybe something else?

Conclusion

We seem to change imaging models every ten years or so. Xlib, then Xrender with Cairo, then GPUs and CSS-based drawing for widgets. We've gone from trusted data on your local machine, to potentially malicious data that rains from the Internet. Gdk-pixbuf has spanned all of these periods so far, and it is due for a big change.

My open source career

- You have to start somewhere: My first patch

- You need a community to support you: 15 years of KDE

- Don’t do it for the money: Don’t sell free software cheap

openSUSE.Asia Summit

openSUSE.Asia Summit is an annual conference organized since 2014 every time in a different Asian city. Although it is a really successful event, which plays a really important role in spreading openSUSE all around the world, it is not an event everybody in openSUSE knows about. Because of that I would like to tell you about my experience attending the last openSUSE.Asia Summit, which took place on August 10-12 in Taipei, Taiwan.

Picture by COSCUP under CC BY-SA from https://flic.kr/p/2ay7hBD

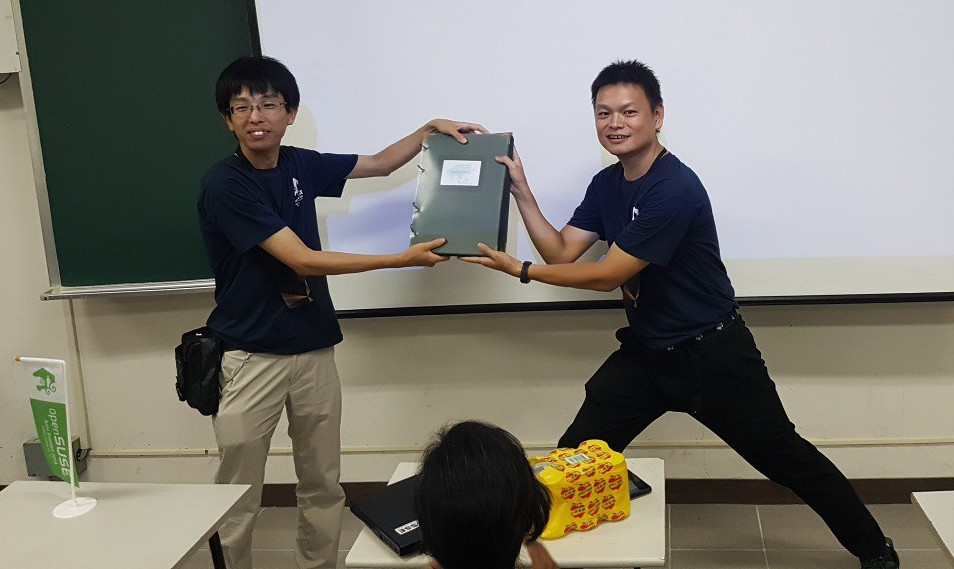

openSUSE.Asia Summit 2018

This year, openSUSE.Asia was co-hosted with COSCUP, a major open source conference held annually in Taiwan since 2006, and GNOME.Asia. It was an incredible good organized conference with a really involved community and a lot of volunteers.

Community day

On August 11, we had the openSUSE community day at the SUSE office. We had lunch together and those who like beer (not me :stuck_out_tongue_winking_eye:) could try the openSUSE taiwanese beer. We also had some nice conversations. I especially liked the proposals during the discussion with the Board session to get both more students and mentors involved in the mentoring in Asia and to solve the translations problems. In the evening, we joined the COSCUP and GNOME community for the welcome party.

Talks

On Saturday and Sunday was when the conference itself took place. Specially the first day it was really crowded (with 1400 people registered! :scream:) Both days and from early in the morning, there were several talks simultaneously, some of them in Chinese, about a wide range of FOSS topics. Appart from the opening and closing, I gave a talk about mentoring and how I started in open source. I am really happy that in the room there were a lot of young people, many of them not involved (yet) in openSUSE. I hope I managed to inspire some of them! :wink: In fact the conference was full of inspiring talks, remarkably:

-

The keynote by Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s Digital Minister, full of quotes to reflect on: When we see internet of things, let’s make it an internet of beings.

-

We are openSUSE.Asia emotive talk by Sunny from Beijing, in which she explained how her desire to spread open source in Asia took her to organise the first openSUSE.Asia Summit.

-

“The bright future of SUSE and openSUSE” by Ralf Flaxa, SUSE’s president of engineering, which surprised me because of being really different to other of his talks I have attended.

-

Simon motivating talk about his experience in open source, packaging and the board activities.

Pictures by COSCUP under CC BY-SA from https://flic.kr/p/29sJhHq and https://flic.kr/p/LPGjaF respectively

Apart from the talks, we had the BoF sessions on Saturday evening, in which we could get together surrounded by A LOT of pizza. In the session, there was a presentation of the two proposals for next year openSUSE.Asia Summit: India, with a really well prepared proposal, and Indonesia, whose team organized the biggest openSUSE.Asia Summit in 2016. There was also the exchange of the openSUSE Asia photo album, preserving the tradition that every organizing team should add some more pages to this album. It is getting heavy! :muscle:

One day tour

The conference ended with another tradition, the one day tour for speaker and organizers. We went to the National Palace Museum, to the Taipei 101 tower and to eat dumplings and other typical food. It was a great opportunity to get together in a different and fun environment.

See you next year

As you see, we had a lot of fun at openSUSE.Asia Summit 2018. From a more personal point of view, I enjoyed a lot meeting our Chinese mentors I normally write emails to. I had also the chance to meet some members of the GNOME board, exchange with them experiences, problems and solutions, and discuss ways in which both communities can keep collaborating in the future. The conference was full of fun moments like seeing a pyramid of pizza (and a hundred of people making pictures to it) and being amused by someone wearing a Geeko costume with 35 degrees and 70% humidity. :hotsprings:

Geeko’s picture by COSCUP under CC BY-SA from https://flic.kr/p/2atN6KE

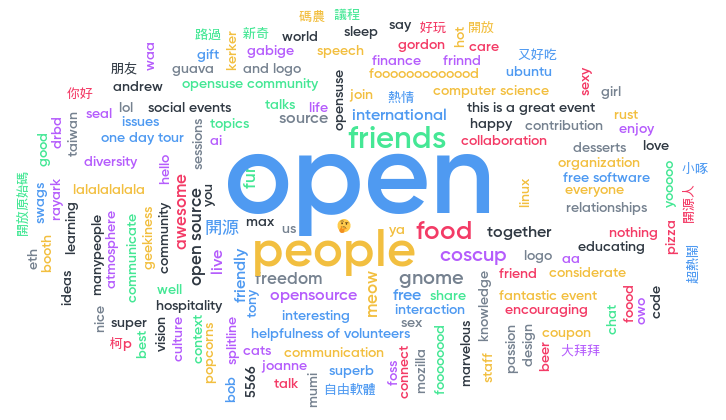

To finish, this is what attendees said to liked the most about the conference in the closing session:

See you next year!

About me

My name is Ana and I am mentor and organization admin for openSUSE at GSoC, openSUSE Board member, Open Build Service Frontend Engineer at SUSE and open source contributor in projects inside and outside openSUSE.

Linux ACL Masks Fun

So I am working on a Nextcloud package at the moment. Something that does not have such brain dead default permissions as the docs give you. To give all users who need access to the files, I used ACLs. This worked quite fine. Until during one update … suddenly all my files got executable permissions.

I ran rpm --setperms nextcloud to reset the permissions of all files and then I reran my nextcloud-fix-permissions. Nothing. All was good again. During the next update … broken again. I fixed the permissions manually by removing the x bit and then rerunning my script … bugged again. Ok time to dig.

Stallmanu

Stallmanu

Member

Member